Out Exclusives

The Hustlers and the Movie Star

Ramon Novarro was the king of the silent screen. In 1968, two very uncommon criminals were arrested for his brutal slaying.

May 23 2012 10:00 AM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

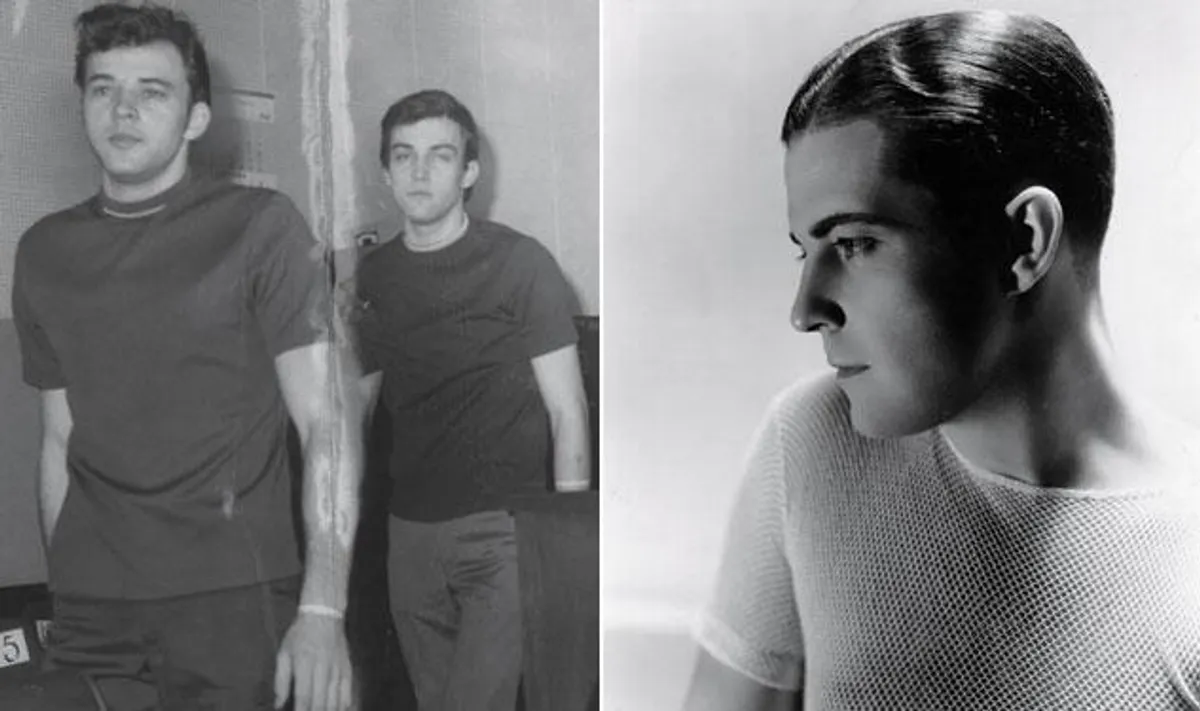

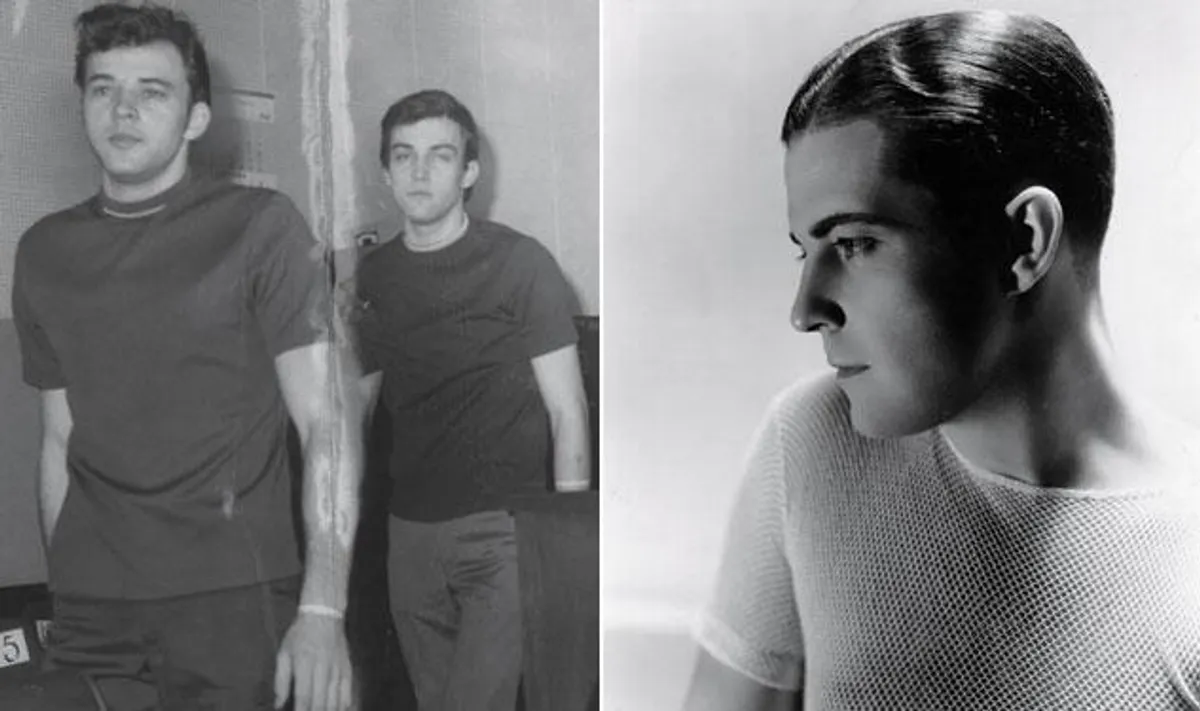

At left: Paul and Tom Ferguson enter the courtroom for their murder trial, 1969. Right: Ramon Novarro at the height of his stardom, 1925.

I

Down the sternly christened No More Victims Road lies Jefferson City Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison about two hours west of St. Louis. It is an unseasonably warm day in mid-February, and Paul Robert Ferguson sits in the visitation area. Behind him is a painting of a soldier saluting the flag and various Plexiglas windows for those prisoners considered unfit to be in close proximity to their guests.

Paul, 66, is wearing all gray--hospital-scrub pants and a tee over a long-sleeved shirt. His graying hair is slicked back in the Rockabilly style of his youth, but the back is grown out and touches his shoulders. Two teeth are missing and, as he speaks, he dips a ham sandwich from the vending machine into a cup of hot chocolate, just to taste something different. The monotonous food is his biggest complaint about prison--that, and missing horses. He maintains his strong build doing 200 push-ups every other day (despite the fact that he's had five heart attacks and sleeps with an oxygen mask on).

"I'm an existentialist," Paul says. "I try not to let the environment dictate who I am."

Paul is a practicing Buddhist and does yoga each morning. He is also a convicted murderer responsible for one of the biggest scandals Hollywood has ever seen.

II

It was 1968, and former silent film star Ramon Novarro had downsized from his Frank Lloyd Wright-designed mansion to a one-story Spanish-style ranch house. The movie roles had long dried up, and he was reduced to the occasional guest spot in TV shows like Bonanza and The Wild Wild West. But the 69-year-old Novarro would soon be front-page fodder again.

Born Ramon Samaniego in Durango, Mexico, Novarro had supported his large family after their move to the states. Novarro starred in silent blockbusters such as 1925's epic Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (the most expensive silent film until last year's The Artist) and Scaramouche. From 1925-1935, Novarro made more money for MGM than any actor except for Joan Crawford. He just about survived the great sea change that was sound, appearing in talkies such as the hit Mata Hari, opposite Greta Garbo, but his career went into decline.

A fervent Catholic and an alcoholic for more than 30 years, Novarro had lost his license due to multiple DUIs (he received two within two days in 1960) and was receiving unemployment. He could no longer pull off being a romantic lead, his previous forte. "Most likely because of alcohol abuse, Novarro aged rather rapidly," says Andre Soares, author of the biography Beyond Paradise. "Also, Novarro seriously considered becoming a monk. All evidence seems to point out that he very much missed the good old days of fame and riches. He did strive to come back a few times, but without any luck."

The 5-foot-6 actor had advanced emphysema and arthritis and weighed 198 pounds. He frequently used an escort service, Masseurs -- The Best, on nearby Fountain Avenue. His secretary of eight years, Edward Weber, was helping him write his memoirs. Weber's other duties included paying the escort service (hundreds of checks were written out in denominations of $20 or $40, often under the ruse of "gardening" services) and making alcohol runs.

Wednesday, October 30, was Weber's day off, but he happened to stop by the liquor store near Novarro's house. The proprietor told him that Novarro had just placed a delivery order for cigarettes -- one carton of Winstons and one of Marlboro. Weber offered to drop them off to Novarro (who didn't smoke). When Weber showed up at 3110 Laurel Canyon Boulevard around 5:30 p.m., his boss appeared at the door in a dressing gown and was surprised to see him. Weber thought that he could smell lotion on Novarro and noticed he had a freshly trimmed mustache and goatee. He wasn't invited in. Weber would later testify, "I had the feeling that he had guests."

Ramon Novarro with Greta Garbo in Mata Hari

The next day, Halloween, Weber reported to Novarro's home for work at 8:30 a.m. The house was in a state of disorder: chairs were overturned, a pair of spectacles was crushed on the living room carpet, and liquor bottles were strewn around. Weber searched the nine-room house. At first, he didn't see anything out of the ordinary in the bedroom; the curtains were closed and no light could come in. After he drew them, he made out the figure of Novarro, nude, lying on his back on his bed, his face severely beaten. Scrawled on the mirror with a brown makeup pencil: US GIRLS ARE BETTER THAN FAGITS. The name LARRY was written in ink on the blue bed sheet next to the body. Scratches were carved into Novarro's neck.

Weber phoned the police, and, within minutes, investigators (and a phalanx of reporters and onlookers) arrived. A newspaper photographer stumbled upon a pile of bloody clothes (a jacket, undershirt, T-shirt, and two pairs of underwear) in the ivy bed on the other side of the 8-foot-high iron fence that separated the property from the lot next door.

The preliminary coroner's report issued later that day read:

"Blood noted (smeared) on floor in bedroom, on ceiling, and tooth noted lying on floor at foot of bed. Decedent's hands were tied behind his back with brown electric cord, (a white condom was found in decedent's right hand) and electric cord extended down and was tied around decedent's ankles. Lacerations and ecchymosis were noted on face and head."

The next day, Novarro's murder made the front page in newspapers across the country. The headline from The New York Times read "Ramon Novarro Slain on Coast; Starred in Silent Film 'Ben-Hur.' " The Los Angeles Times chimed "Ramon Novarro, Silent Film Era Star, Beaten to Death." Police announced that the murder weapon had been found, a silver-tipped cane.

The final autopsy report revealed that Novarro's blood alcohol level was .23 (today's legal limit in California is .08). He had a fractured nose, and there was bruising on his chest, neck, left arm, knees, and penis. The cause of death was determined to be suffocation. Novarro had choked on his own blood, due to "multiple traumatic injuries of face, neck, nose and mouth."

III

On October 21, nine days before the murder, 17-year-old Tommy Ferguson arrived in Los Angeles. In March, he had escaped from an Illinois reform school where he had been sent for beating up an older man and robbing him. Wanting a fresh start for him, his grandmother had put Tommy on a plane with instructions to stay with his 22-year-old brother, Paul, and his wife of three months, Mari, in their Gardena apartment.

When Paul was growing up, the Fergusons were an itinerant family, depending on where their father, Lucky, would find work as a steeplejack (repairing and painting steeples, towers, bridges, anything high and dangerous). Lucky was a daredevil even when not working. Once, when he had a broken leg, he jumped off a high bridge into a river carrying Paul, a toddler at the time. The family would move between Alabama and Illinois. This was no small feat. Lorraine and Lucky had 10 children; Paul was the oldest. "He'd wake you up in the middle of the night and say, 'Look what I caught,' " Paul remembers of his father. "The whole bathtub would be full of big ol' catfish. He was a good guy when he was sober. He was a womanizer and he'd rather drink than buy groceries or pay rent. He was a regular piece of hillbilly shit."

Lucky would disappear for weeks at a time, leaving Lorraine with the kids and no money. When he was 10, after being struck by his father, Paul left home and hitchhiked from Florida to his grandmother's in Chicago, eating wild onions on the way. Lucky died of spinal meningitis when Paul was 12. At 14, Paul left home for good and hitchhiked to Mexico and then to Wyoming to work as a rancher. At 15, he joined the army, by lying about his age, and was honorably discharged a year later.

Lorraine married Norman Smith and had two more kids (Paul got into a physical altercation with Norman at their wedding). Tommy and Paul were not close, but the brothers' names and fates would soon be inexorably intertwined, a blood bond not just in fraternity, but also in lore and crime. But that was days away. Tommy and Paul had wildness in common. Tommy had been in and out of juvenile detention centers and mental institutions. Tommy had run away at 15. They didn't grow up together for very long in the same household. They had both dropped out of school, but were exceptionally smart.

Paul admits that Tommy was sharper than he was. "He was real smart, probably smarter than me," Paul says, "but it was like he devoted that intelligence to fucking shit up." The first thing that comes to Paul's mind when thinking of his brother was him wetting himself when he was too old to be doing so.

And now, Tommy was in Los Angeles, sleeping on his couch. Paul had last seen Tommy two years prior. Paul had been living in Dallas, and Tommy hitchhiked through. On the second day of staying with him, Tommy stole Paul's girlfriend's jewelry, pawned it, and took off.

At 6-foot-4, Tommy -- lanky with an angular face -- was taller than Paul, who had the build of a welterweight boxer. Tommy's general comportment made Mari nervous, and he was another mouth to feed. "When you first met him, he was real nice," Paul recalls today. "He was intelligent, but weird. He was able to go from light to dark when you looked at him. He could look like Boris Karloff in a minute, and other times he'd look handsome."

It wasn't long before Mari told Paul that she didn't want Tommy there. This was Paul's third marriage. When he was 16, he married a 42-year-old woman (it was annulled nine months later). Another marriage at 19 ended in divorce. Paul met Mari through her brother, Larry Ortega. Tall and handsome, Larry was a prostitute and had worked for the infamous arranger "Mr. Richard." Larry also arranged meetings for his fellow hustlers on the side, and sometimes tried to get Paul to do jobs for him. Larry had been friends with Paul and always told him that if he met his sister he'd fall in love with her. Sure enough, that's what happened, and they married shortly thereafter.

As the oldest child, Paul hustled to contribute to the household. "I was selling myself to feed my family while my dad was out doing radio towers," he says. "When I was 10 years old, I would sell myself to the local pervert to get meat, beans, and bread to take home." Paul wouldn't consider what he had done since moving to L.A. hustling. "I was a houseguest," he explains. "There's a difference. Not much, but there's a difference. It's better to be a houseguest, I think. But, you know, I had relationships on that level." Sex was involved, but Paul attests that it was more of an afterthought, that he had real friendships with the patrons, that they weren't solely clients. In June of 1964, Paul had posed for nudes in Chicago with physique photographer Chuck Renslow who remembers Paul as a hustler recommended to him by a friend. "He was gorgeous, his butt was beautiful," Renslow says. "But he was very sullen and didn't smile." Paul also appeared in a couple of porn films.

Just before Tommy's arrival, Paul had been laid off from his contracting job, and he and Mari were penniless. On October 29, Mari and Paul got into a heated argument (about a can of evaporated milk) that exacerbated the situation. Mari left to stay at her parents' house. It was just Paul and Tommy in the apartment now. Tommy told Paul that he sometimes hustled for money. "He did dumb things like that," Paul remembers, "like he was confessing and I was the priest or something. I said, 'You can't stay with me, but maybe I can fix something up. There's gay people who might put you up.' "

Paul phoned Victor Nichols, a real estate developer with ties to the hustling world, for leads on unloading Tommy. "He asked if Tommy was good looking," Paul recalls. "I said, 'Sure.' He gave me Novarro's number and I called and talked to him about Tommy. Novarro says, 'OK. Come on up.' " Tommy would later testify: "When Paul and Mari broke up, I felt it was my fault. Paul was in bad shape. I was a nuisance to him. I was just ready to get drunk... I was bored with California. I wanted to go back to Chicago. Paul said we were... going to meet a homosexual for some drinks, and one of us would have to go to bed with him."

The next afternoon, the brothers hitchhiked from Gardena to the West Hollywood home of one of Paul's friends-with-benefits with whom he had briefly lived -- the friend would sometimes drive Paul to his rendezvous with men. Paul asked for a ride to Laurel Canyon. Around 4:30 p.m. they were dropped off outside of Novarro's home.

Novarro came to the door in a blue and red silk robe and invited the brothers inside. Paul had vodka while Tommy drank beer and tequila. Novarro read Paul's palm and told him he had a long lifeline. Paul plinked "Chopsticks" and attempted "Swanee River" on the piano. Novarro served them chicken gizzards and ordered cigarettes from the liquor store. In an effort to flatter and impress, Novarro told Paul that he had Hollywood qualities. "He said I could be a young Burt Lancaster, a superstar, another Clint Eastwood," Paul would later testify. Novarro went so far as to phone his friend, a press agent, and suggest a meeting. That would be the last anyone would hear from Ramon Novarro.

Paul Ferguson in court

IV

After they left Novarro's house, the Ferguson brothers walked to the apartment of Victor Nichols (who had given Paul Novarro's phone number in the first place). Tommy napped on the leopard-skin sofa while Paul told Nichols that Novarro was dead. Eager to get them out of his apartment and not involve himself, Nichols gave Paul eight dollars for taxi fare back to his apartment.

The days after Novarro was killed were a blur to Paul. "I just kept thinking, What am I going to do? And there's no answer. It was a lost week. It was just empty. I would put a pot pie in the oven and it would be there two days before I realized it was still in," he remembers. The pair walked about 15 miles from Gardena to Bell Gardens, to the apartment of a former coworker and friend of Paul.

He continues, "We walked and walked. Tommy would question me and I'd tell him to shut up. There's no reason or rhyme. It was just being lost. There was no direction to go. There was no place to go. What could I do? There was nothing to do. It was over with."

The police immediately started questioning known male prostitutes, and Paul's name came up in some interviews. They took particular interest in Paul's brother-in-law, Larry Ortega, due to the LARRY written next to the body (Larry had, in fact, spent the night with Novarro the week prior and often rented his services to him). But Novarro's phone record was the real beacon. Police traced a 48-minute call to 19-year-old Brenda Lee Metcalf in Chicago, made at 8:21 p.m. on October 30. When Chicago police interviewed her, she told them that she had been speaking to her boyfriend of about six months, Tommy Ferguson.

In her statement to Chicago police, taken weeks after her initial interview, Metcalf said: "He told me that he and his brother were invited to this movie star's house... Then he told me he was working and trying to save enough money so he could send me about $300 so I could come down there and get married... I don't know how he got on the subject, but Tom told me that his brother knew there was $5000 behind one of the pictures in the house, and that they were going to try to find it." The "$5,000" amount in Metcalf's statement wasn't present in her initial interview with police weeks prior and would end up being a crux of the case. Also, no fingerprints from the Fergusons were found on any picture frame on the walls. Metcalf's statement continued: "Tom said my brother was upstairs with Ramon and he was trying to find out where the money was... Then I heard a little bit of yelling and... and Tom said, 'I have to go before my brother really hurts Ramon, and I wanna find out what's going on,' and that was the end and he hung up."

The Fergusons both had records in Chicago (Tommy had an extensive juvenile rap sheet, and Paul had served time for taking a rented car across state lines). Their fingerprints were rushed to Los Angeles. Police determined that they matched samples taken at the crime scene. On November 6, detectives arrested the brothers in Bell Gardens; Tommy was in the apartment of Paul's friend, and Paul was in a nearby diner.

During the interrogation, Sergeant Robert Smith asked Paul about his hustling: "And you bang these fruits really hard frequently and you stomp them?" Paul answered, "That's a lie. There's nobody in the world that ever said I stomped a fruit or hit one. And that's the God's truth." When asked if he used the term "faggot" derogatorily, Paul responded, "They're no different from anybody else. They're my friends. If I meet one on the streets, I don't cross the street." At first, Paul denied having anything to do with the murder. Later, he said that he passed out, and, when he awoke, Novarro was dead.

During his interrogation, Tommy said that, after the phone call with Brenda, he went to the bedroom, where Paul had gone to be intimate with Ramon. Tommy said, "Ramon was all hit in the face and all that stuff, ya know, and the back of his head was bleeding and then I took him into the shower, you know, to wash off." Tommy alleged that the next day Paul told him, "He died bravely... That's all he wanted out of life was to live and suck a few dicks."

At his arraignment, Paul was ordered to be held without bail pending trial. The juvenile court ruled that Tommy be tried as an adult. The brothers were charged with murder and tried together. Deputy district attorney James Ideman was assigned the case.

"I saw them as tough kids," Ideman says. "They were called hustlers at the time. I'm not sure if that word is still used. They were looking to make a buck and possibly have sex with men for money. They wanted to steal or rob if they saw the opportunity."

At county jail, Paul got into an altercation with a group of black inmates. "This black sergeant asked me about it. I told him, 'Look man, you're just another nigger, you don't care what the fuck happened,' " Paul says, "and he put me in the hole." Paul remained in solitary for the duration of his stay. By the time the trial had begun, he'd contracted hepatitis C and lost 29 pounds.

V

The summer of 1969 was a season of turmoil and upheaval, war and protest. As the Vietnam War raged, closer to home, in burning Los Angeles, the Tate-LaBianca murders committed by the followers of Charles Manson darkened the city.

The State of California v. Paul Robert and Thomas Scott Ferguson began on July 28, presided by Judge Mark Brandler. The charge was first-degree murder. "We were asking the death penalty," Ideman says. "They didn't intend to kill him, but it was a felony murder if a death occurs in the course of a robbery. It was not premeditated, they didn't go there with the intention of taking his life, just his money." There was no charge of robbery, however. The only thing taken from the house was a shirt to replace Paul's bloodied one used to mop up the crime scene. Richard A. Walton, a court-appointed attorney, represented Tommy. Cletus J. Hanifan was Paul's lawyer (paid for by extended family).

Ramon Novarro's problems with alcohol were well-documented during his lifetime, but his sexual proclivities, an open secret in Hollywood circles, had been closely guarded from the public. Every aspect of his sex life was now to be examined. "Mr. Novarro was a homosexual and probably had been one for many years," Ideman said in his opening statement. "But he was a discreet homosexual. He did not go into the streets and try to pick up people. The young male prostitutes would come to his home, and he was usually careful about who came to his home."

Over objections from the defense that her testimony would amount to hearsay, Metcalf took the stand to recount her phone call with Tom, including the reference to the $5,000. Paul's landlady was called and claimed that Paul was late on his rent (he had in fact paid it early) and had mentioned to her that he was coming into $5,000 nine days before the murder, proof of pre-meditation if true (Paul denied this exchange altogether, and her veracity was doubted by officials, but possibly not the jury).

The defendants and their counsel sat behind the same table, but it was a forced proximity -- there was no effort to put on a united front. Hanifan and Walton pitted their clients against each other. Paul testified that he had passed out after drinking too much and awoke to Tommy telling him, "This guy's dead." Tommy testified that he had walked through the bedroom and had seen Paul and Novarro nude on the bed, and that the second time he entered, Novarro was alive, albeit bloody, and that's when he helped shower him.

Tommy testified that Novarro then said, "Hail Mary full of grace, the Lord is with thee," at which point Paul hurled a pen at his brother on the stand and screamed, "Oh, you punk liar son of a bitch! Tell the truth!" and was reprimanded by Judge Brandler. Tommy added that Paul donned a vest and bowler hat, waved a cane around, and danced, vaudeville style, covered with blood.

Tommy Ferguson consults with his attorney Richard A. Walton

Paul and Tommy's mother, Lorraine Smith, was next on the stand. It was the first time she had seen her sons since their incarceration (she hadn't seen Tommy since he was 15). She testified that Tommy wrote and told her that Novarro "deserved to be killed. He was nothing but an old faggot," but did not produce the letter. Her testimony put the burden of blame squarely on Tommy.

A letter from Smith to Tommy dated May 27 was introduced into evidence by his defense. It read in part: "Paul Robert wrote the first trial day and said everyone seems out to save his own skin and he's in a corner now. Tom, when you testify, think about what you're saying. You're holding Rob's life in your hands. You can either let him live or die."

That day, Smith spoke to the Los Angeles Times: "She said her younger son had been in an Illinois mental institution twice and had been in and out of jails and juvenile halls since he was 13. She believes he is capable of violence... 'I was deathly afraid of him,' she said.' " She told the paper that Paul hadn't been any trouble.

During his closing argument on September 15, 1969, Ideman waved crime-scene photos at the jury. "What kind of monsters would do a thing like this?" he asked. "These two male whores are experienced. They've lived on the streets for years. Why all of these serious injuries if not to get him to tell where the money was?... Novarro was paying a lot of young men for a long time."

He closed with, "Neither of the Ferguson brothers will admit striking Mr. Novarro even once... I was beginning to wonder if what we were dealing with was a suicide. Perhaps Mr. Novarro wrapped himself in that electrical cord and beat himself to death."

Hanifan maintained that his client, Paul, had been asleep during the murder, and that it was committed by Tommy. Besides placing the blame solely on Paul, Walton cast his net wider. "Back in the days of Valentino, this man who set female hearts aflutter, was nothing but a queer," he told the jury. "There's no way of calculating how many felonies this man committed over the years, for all of his piety. What would have happened that night if Paul had not gotten drunk on Novarro's booze, at Novarro's urging, and at Novarro's behest? Would this have happened if Novarro had not been a seducer and a traducer of young men?" Walton accused Paul and his mother of conspiring to focus the blame on Tommy so Paul could avoid the gas chamber (Tommy wouldn't face the death penalty because of his age during the crime).

The jury deliberated for two days before finding the Ferguson brothers guilty of first-degree murder. At the sentencing hearing, Tommy confessed, "He kept trying to put his fingers up my rectum... I started hitting him... I hit him again, and he hit the floor." He then added, "He died of a broken nose, and I'm the one who busted it." Ideman urged the jury to ignore his confession and maintained that Paul had been the aggressor. The brothers were sentenced to life, a punishment to be served at San Quentin.

VI

"In my neighborhood in California, we did not bless the door that opened wide to stranger as kin. Paul and Tommy Scott Ferguson were the strangers at Ramon Novarro's door, up on Laurel Canyon," wrote Joan Didion in her treatise on 1960s Los Angeles and the last gasp of the summer of love.

As the Fergusons served their sentences, the legend of their crimes infiltrated pop culture. Charles Bukowski wrote the thinly veiled "The Murder of Ramon Vasquez." Salacious magazines featuring crime scene photos and the nude images of Paul were rushed into production. Truman Capote interviewed Paul for a 1973 TV special on the prison's death row. The most infamous reference to the murder, however, was the section in Kenneth Anger's remarkably entertaining (and inaccurate) exploration of decadence, Hollywood Babylon. He asserts that the murder weapon used to kill Novarro was a lead dildo cast from Valentino's member, and that it was crammed down his throat suffocating the actor. The phallus didn't exist, but this urban legend still persists.

In the 1970s, an avid fan, Ryan Kelly, who often dressed like Novarro, purchased his home (along with some of his furniture). He claimed that Novarro haunted it. Kelly was killed in the late '80s by his brother with a shotgun up the street from the house. The house has since been demolished.

Paul and Tom Ferguson enter the courtroom for their murder trial, 1969.

VII

San Quentin was famous for being one of the most violent facilities in the nation. One of Paul's first jobs at the prison was picking up bodies and wheeling them out of common areas on a gurney. "There were frequent stabbings," says Jim Parks, the associate warden at that time. "Murders everyday is a little exaggerated. One week we had five murders, but that didn't happen every week." Parks remembers Paul well. "For a convict, he was a pretty straight-up guy -- and not like the rest of the hoodlums," he says. "He made a point of staying away from most of the convicts."

Paul thrived in the harsh environment. He was the host of the prison's radio station and conducted interviews. He studied welding and sheet metal work, and also creative writing. He received an associate's degree from the College of Marin. In 1975, he won a P.E.N. award for his short story, "Dream No Dreams." People wrote a small piece about Paul winning the award, and he gained an admirer, a married woman, who would leave her husband for him. They were allowed conjugal visits and were later married.

Tommy made frequent escape attempts and was often relegated to solitary. Paul was allowed out of prison to work in a forestry camp as part of his rehabilitation. "I saw Tommy the day I went to forestry camp," Paul says. "I gave him my TV and radio. It was my third time giving him my TV and radio. He was hocking them for drugs. He was doing everything -- marijuana, cocaine, glue." This would be the last time Paul would ever see Tommy. The brothers were paroled after serving seven years, but never spoke again.

Tommy continued his trajectory established in San Quentin. He married his prison psychiatrist, a woman in her fifties, and briefly worked in a mental institution. The marriage didn't last. He had a daughter with his second wife, but that marriage also ended in divorce. Paul and Tommy's younger sister, Denise Vignes, recalls of Tommy: "He was calling my mother. I guess he'd get drunk or manic or whatever. I remember him saying, 'I'm going to kill you.' It got to the point where my mom said, 'OK, Tommy, come on down. I'll be out in the street.' And she went out there and he never showed up. That's all we heard from Tommy. He never tried to rejoin the family."

On January 18, 1987, the Associated Press reported, "Thomas Scott Ferguson, a drifter on parole after a prison term for the slaying of silent-film star Ramon Novarro, was sentenced to eight years in prison for raping a 54-year-old Chico woman." He was paroled in 1990. In 1991, he racked up multiple charges of public intoxication, failure to appear in court, and petty theft.

Vignes says that, upon his release, he briefly stayed with one of their brothers and his partner. "Sometimes they would come home and all of the pillows would be slashed with a knife," Vignes says. "They would look for Tommy, and he would be sleeping on the roof. He didn't like to be by people at night."

"I think Tommy didn't feel loved," she continues, "and my mom would be very mystified about this. She'd go, 'Tommy would be six years old, sitting there watching TV, and just take a leak in his pants on the floor.' Tom told me that he was scared to death all the time. Back then, we didn't have all that psychology and what to do with a kid. I think Tom got lost in the shuffle of 12 kids."

Tommy served time for failure to register as a sex offender when he moved to Palm Springs. "He felt like he was carrying this whole Novarro thing his whole friggin' life," Vignes says. "He was so adamant with me: 'I was on the phone with my friggin' girlfriend when that happened. I never touched the fucking guy.' " Tommy committed suicide on March 6, 2005. "He went to Motel 6 and cut his throat. No letter no nothing," says Vignes, who had to identify the body.

Paul Ferguson at the Jefferson City Correctional Center

VIII

After his release from San Quentin, Paul married again and had a son. He was a successful entrepreneur, doing such disparate things as owning a restaurant, a rodeo, a nightclub, and a racetrack. A remarkable collection of his autobiographical short stories, No More War Stuff About God, Anymore, was published by a small imprint in 2009. For a time, he followed in his father Lucky's footsteps and was a steeplejack. Paul is currently serving a sentence of 60 years for a 1989 rape and sodomy charge.

Paul contends that the prosecutor, Christopher J. Miller, who is now the district attorney of Ripley County, Mo., framed him. Paul alleges that Miller had represented him in a previous real estate deal and shouldn't have been prosecuting the case (Miller denied an affiliation with Paul). Paul filed an appeal for Habeas Corpus in 1996, among the documents supporting a relationship were affidavits and a receipt from Miller's firm. Paul's request was denied (Miller didn't respond to requests for comment).

Reclining in a blue plastic chair in the prison's visitation room, Paul discusses the events of October 30, 1968, at Ramon Novarro's house. "I'm drinking and listening to him talk about the movies," Paul says. "I'm going, Wow, this guy can tell some pretty good stories. But I'm getting drunk. The next thing I knew, I find myself being overwhelmed by this body, and just, like, hairiness, and I guess being kissed or whatever the fuck it was. And I come out of that, I go, 'Get the fuck-,' and boom, and I walked out. So, that's what happened. So of murder I was innocent. Of manslaughter, I wasn't innocent. Even of manslaughter, maybe you could say I was innocent, but I was guilty of hitting him. I did hit him, but I did it in a drunken stupor."

Paul insists that what the police referred to as a "striking instrument," the cane, was manufactured evidence, that he never saw it until it was exhibited at trial (the cane is listed on the original preliminary autopsy report, however, as is the condom in his hand, which Paul says was planted, too, he thinks by detectives). Paul maintains that there was no murder weapon. He continues, "I'll tell you what, I'm a boxer. When I hit you, I probably hit you three or four times. I remember standing beside this man and coming out of this heavy drunken fog and hitting him and seeing him fall on the bed. But I didn't do anything more than that. Mr. Novarro died because he was so drunk that the blood in his throat; the involuntary muscle in his throat didn't work because the alcohol suppressed it. If he had turned his head, if he had been a little more sober, he would not have died. That's the God's truth."

Of Tommy's involvement, Paul says, "Basically nothing. He was supposed to be staying there. He was on the phone to his girlfriend, and he heard me hit Novarro. Next thing, I was sitting on the couch and I went back in the front room. I poured a drink and sat down on the couch and I dozed off and he came in there and said, 'You gotta come with me.' And I went in there, and he pointed at Novarro and said, 'This guy's dead.' Mr. Novarro was lying on the floor, and we picked him up and put him on the bed. Then we got the brilliant idea: Let's make it look like a robbery."

Paul continues, "I was telling my lawyer and mother what happened, and they said, 'You can't say that because you will get the gas chamber.' Tommy got wrapped up in the circumstances, but was crazy and didn't know what to do. He had a huge IQ, but it worked against him. Sometimes being so smart makes you dumber than shit. You think you can outthink people when you're way off in the clouds."

"As far as Mr. Novarro, I came to peace with that a long time ago," Paul says. "I'm at peace with: what happened, it was not intentional; it was an accident. I'm not at peace that a human being is dead and I was a part of that. That has haunted me. I never deliberately hurt Mr. Navarro. I am absolutely responsible, but it's not the things that you do, it's the things you do intentionally. It's who you are. You have a lot of shit written on your brow with your regrets. And I don't know what role it played in my brother Tommy's suicide either. I have to wonder about that."

When Paul gets escorted back to his cell, a letter awaits him. The Missouri Supreme Court approved his request for an appeal hearing. "What will come of this might be my freedom," he writes in a letter later in the week. "I've all the evidence to prove what I say."