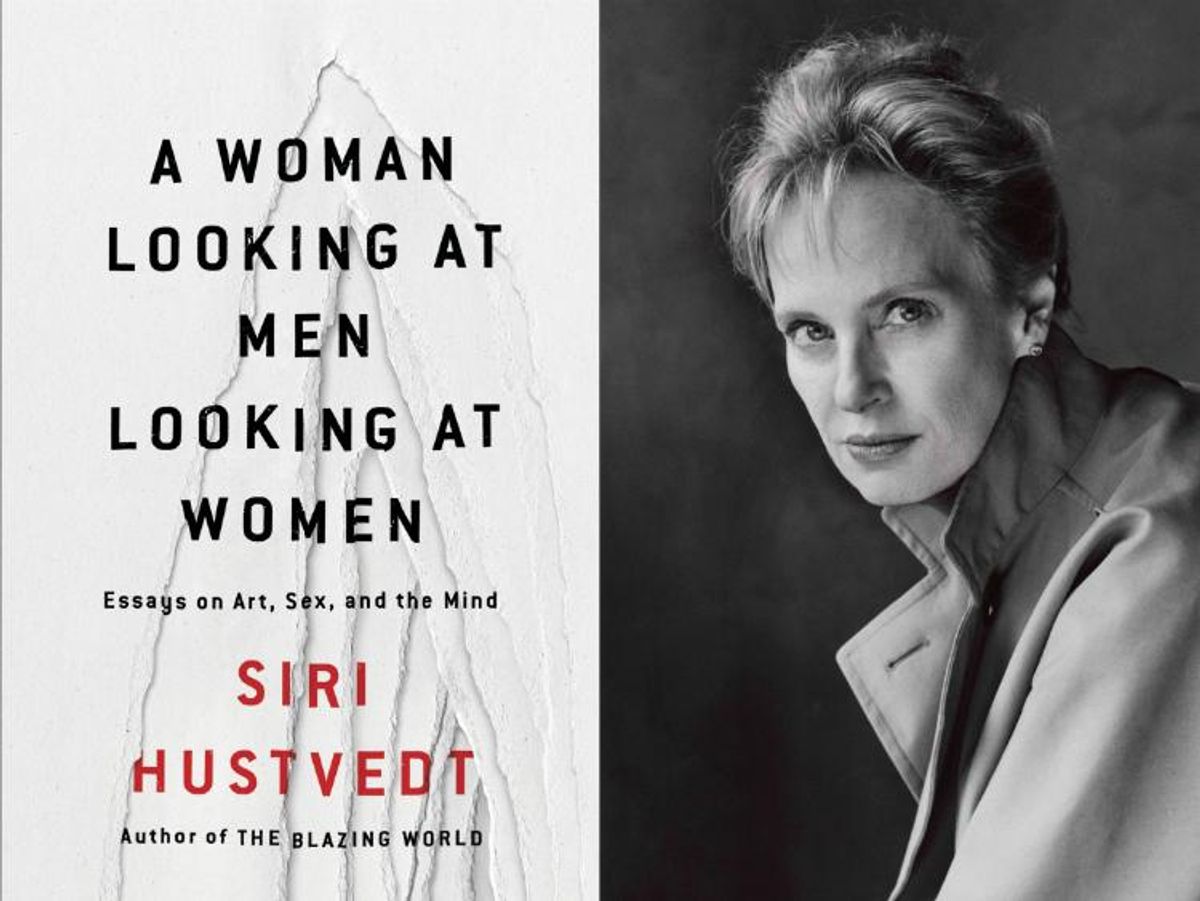

Photo of Siri Hustvedt by Marion Ettlinger.

In her new work, A Woman Looking At Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex and the Mind, prolific writer Siri Hustvedt dives into haunting, every day questions: What is thinking? What is a mind? How can we understand the relationship between art, sexuality, and gender? With a systematic investment in bridging the gap between science and the humanities, Hustvedt has produced a series of essays that explore the mysteries of our linguistic system and the structures that put power, gender, and sexuality in tension with one another.

Navigating through male representations of women in art in the first section of the work, Hustvedt brings to light flawed perspectives, often enriching or adding complexity to a viewer's relationship to the bodies depicted within a frame--whether a painting, screen, or page. She then moves forward with a scientific approach and pinpoints the moments when a person can explicitly notice his or her mind coming into shape; this involves, but is not limited to, the rise of sexuality, the identification with a specific gender, and the place the chosen body will have in the society. To conclude her work, Hustvedt zeroes in on her own practice: masterfully letting her language unravel into a self-reflexive critique.

Out: How did this work come about? Did you intend for the book to be a short essay collection with a larger exploration at its center?

Siri Hustvedt: All the essays in the book were written over a four-year period--between 2011 and 2015. I would say they represent half my life, the half that writes nonfiction and is immersed in science as well as the arts and humanities. I think of the book as a trilogy, three books in one. I have foreign publishers who are publishing them one at a time at six-month intervals. The middle section is a 200-page essay on the mind-problem that just whooshed out of me. The problems and irritants it treats had been building up in me for a long time.

In "Much Ado About Hairdos," you explain that accessories participate in the performance of gender. Do you feel as though children are still subject to gender-expectation or have accessories become relatively gender-neutral?

I think children are still under tremendous pressure to conform to one side of the gender binary or the other. The culture is changing, and children are freer than they were, but the conventions remain brutal. What is now called heteronormativity allows girls greater sartorial freedom than boys, for example. A girl dressing up as a boy doesn't come with as many assaults as a boy dressing up as a girl. And yet, the freedom girls have also connotes their oppression. The boring men's suit remains the garment of power. My utopian fantasy is that every person could indulge his clothing desires without sanction. Wouldn't that be lovely?

What kind of expectations do you think nonfiction has of its reader? How do you create an intimate reading experience?

I have been writing both fiction and nonfiction for a long time. Writing novels always means becoming someone else, and entering the plural reality of many characters. Writing nonfiction means remaining in the single voice of an argument. Nevertheless, over time, my fiction and nonfiction seem to have formed an alliance. In both, I like to apply multiple perspectives to one problem.

My last published novel, The Blazing World, is told in 19 different voices, each of which has a different perspective on the same story, and they do not agree about that narrative. The reader is called upon to enter the ambiguities that appear among all those different voices and make some sense of the story for herself or himself. I think that that's what I'm also asking the reader to do in my mature nonfiction: Look here, there are all these possible ways of thinking about what the mind does, what the body is; or, how we dress or what we do with our hair. You can take almost any sort of object and then say: Look how complicated and interesting all of this is. Maybe I can take you on a journey into some of those complexities and push you into thinking about them in another way. That's what's really interesting. We don't have to buy into the readymade schemas out there in the culture--whether it's hormones, sex differences, psychology, the brain, or hairdos. Give me anything! Usually there is some deadening cultural truism that goes along with it. My interest is in breaking them up.

In "No Competition" you address homophobia by way of Michael Kimmel, who explains that it is "the fear that other men will unmask us, emasculate us, reveal to us and the world that we do not measure up, that we are not real men." In 2016, the gay community is effectively normalizing, infiltrating politics, pop culture, and science. Has the paradigm shifted?

At this moment of political backlash, it's difficult to get our bearings. Personally, I've always thought about sexuality as a fluid business, although it may be less fluid if your particular sexual desires are threatened. Many supposedly heterosexual people have homosexual fantasies and adventures. A dear friend of mine had only male lovers until she was well into her 50s. Now she is happily living with a woman, but she told me she had never wanted a woman sexually until this woman came along. The erotics of ordinary life are rich and complex, and in the age of Trump we must fight to protect the differences of our desires.

Where do transgender people fit into this equation?

As I said, my utopian ideal for sexuality is fluid, a continuum of masculine and feminine rather than a fixed notion of either. In one of my essays, I cite a case from the '80s of a person who identified himself as transgender, but did not use the pronoun "she" and did not dress as a woman. After his partner died, he sought help from a hypnotist and developed pseudocyesis--a false pregnancy. The wish altered his body. A person who feels he or she is in the wrong body must be free to do whatever he or she wants. My question is: What is a man and what is a woman? What are we talking about, and how does trans-sexuality either confirm or threaten those ideas?

The implication of gendered pronouns is that those who identify with plural pronouns do not fit in the scheme. What is your take on this?

I've always understood the reasoning behind the pronoun "they," and there's something lovely about identifying oneself as plural. I think we are all plural realities. In the novel, plurality is allowed free reign. At the same time, "they" is awkward grammatically as a designation for just one person. But then language is about use and once a phrase or a pronoun is used often enough, it becomes part of the language.

Purchase A Woman Looking At Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex and the Mindhere.