Before he became the controversial artist who helped shape a cultural and sexual revolution, Robert Mapplethorpe was a shy altar boy born in a military family. He once considered becoming a priest, as his friend and creative partner Patti Smith recalled when she introduced Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive, a new book focusing on the creative process behind the photographer's work.

"Robert loved art books," Smith said in her opening remarks at the book launch, held at the Rizzoli bookstore this week. "He wasn't much of a reader, in fact he hardly ever read. But he would look at art books for hours and hours on end. He would just absord them. One of his great dreams was to have a big coffee table book. I always thought that was such a strange dream to have a coffee table book of one's work. He didn't really live to see this happen, but many many beautiful books have been done that fit nicely on a coffee table, and of course, this latest one, his archive, is especially wonderful."

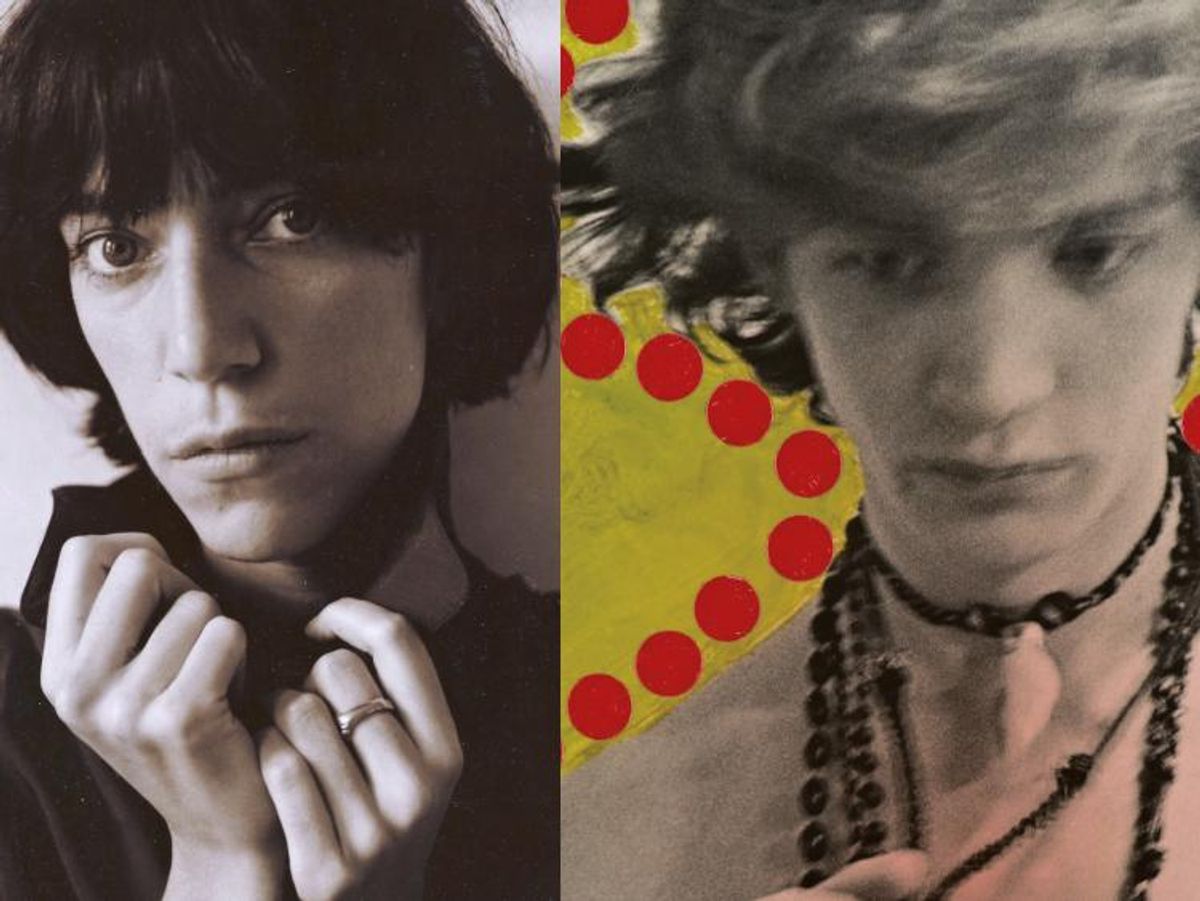

Indeed, the unveiling of Mapplethorpe's personal collections gives new insight on his body of work. Before finding the "perfect medium" in black and white polaroid photography, the artist dabbled in sketching and creating all sorts of artefacts, jumping restlessly from subject to subject.

RELATED | 18 Treasures from Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive

"For a while, Robert was doing these very delicate drawings that in some ways, he says, reflected his experiments with LSD," Smith said. "I thought they were beautiful and I was very attached to them, but it was very bad to get attached to things that Robert did. Because he was like Picasso. You would get attached to this type of drawing, and come home one day, and he would be doing all religious pictures. Cutting out various holy cards, reinventing them, working them into collages and montages, making boxes for them. And I fell in love with them, but then one day I came home, and he had taken this big book on Tod Browning's movie Freaks and was cutting all the freaks out, and he was creating game boards. It was a whole new avenue. Sometimes it would be that quick. I'd leave in the morning and he was, you know, dancing with saints, and when I'd come home at night, he was dancing with freaks."

As Mapplethorpe became more involved in making art, he also began to struggle emotionally with his sexuality. A bright student who finished high-school at 16, Mapplethorpe won a scholarship and attended the Pratt Institute's Graphic Art and Design program, but as graduation neared, he refused to take the exam for his social psychology class. Why? He rejected the definition of homosexuality he found in one of his textbooks, which classified it as a disease.

Mapplethorpe had to let go of his scholarship, and left the school to focus on his own projects. Then, he met the love of his life, his mentor and benefactor Sam Wagstaff. Meanwhile, Mapplethorpe's relationship with Smith continued, albeit in a platonic way, and the pair remained creatively entwined until the artist's death from an AIDS-related illness, in 1989.

RELATED | Why We Can't Forget Robert Mapplethorpe

"I'm especially moved by this book because ever since I met Robert in the summer of 1967, I got to see him execute many of the early works that are in [it]," Smith continued. "When I came to New York City, I was 20 years old. Plan A was to be an artist. Plan B, if I wasn't really good enough, was to be an artist's mistress, which horrified my parents that I had that as a goal. But I dreamed of having some kind of relationship like Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. I just thought it would be the most wonderful thing. So in the summer of love, I came to New York, I didn't have money, I didn't have a job, but one wonderful thing happened to me: I met Robert Mapplethorpe, who also had no money, no job, not even a real place to live."

From his early experimentation with religious imagery to the intricate jewlery he used to craft with Smith, The Archive offers a fascinating glimpse of the artist's evolution. Nothing was too sacred for Mapplethorpe. Organized chronogically, the book culminates into his extreme, sexually-charged photographs of gay S&M and fetish communities. But there's also a fount of undiscovered memorabilia that prove to be real gems to the Mapplethorpe enthusiast: old notebooks, an extensive collection of vintage beefcake imagery, polaroids of his and Smith's interior back when, and reproductions of his more commercial work for the likes of Vogue and the New York City Ballet.

One also gets to see some of his most infamous photographs before their final rendering. For instance, we learn that his "Mr. 10 1/2" originally showed the face of the subject, the porn star Mark Stevens. It was Mapplethorpe's choice to center the frame around Stevens's impressive member.

With over 400 illustrations, The Archive is an exhilarating survey of a virtually unknown trove of inspiration, revealing the artist's impeccable eye as a curator and collector. The scrapbook-style volume opens with an essay by Smith entitled "Picturing Robert," which is followed by a handwritten letter penned by Mapplethorpe to her shortly before his passing.

This book comes out as a companion to the exhibition Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium,on view at both the J. Paul Getty Museum and LACMA (through July 31, 2016). A sister publication entitled Robert Mapplethorpe: The Photographs is also out this month, coinciding with the exhibition, Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium at the Getty Museum's Center for Photographs.

Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive by Frances Terpak and Michelle Brunnick

With essays by Patti Smith and Jonathan Weinberg, $49.95, Getty.edu