Much like his close friend Bjork, Icelandic writer Sjon is now a one-word celebrity.

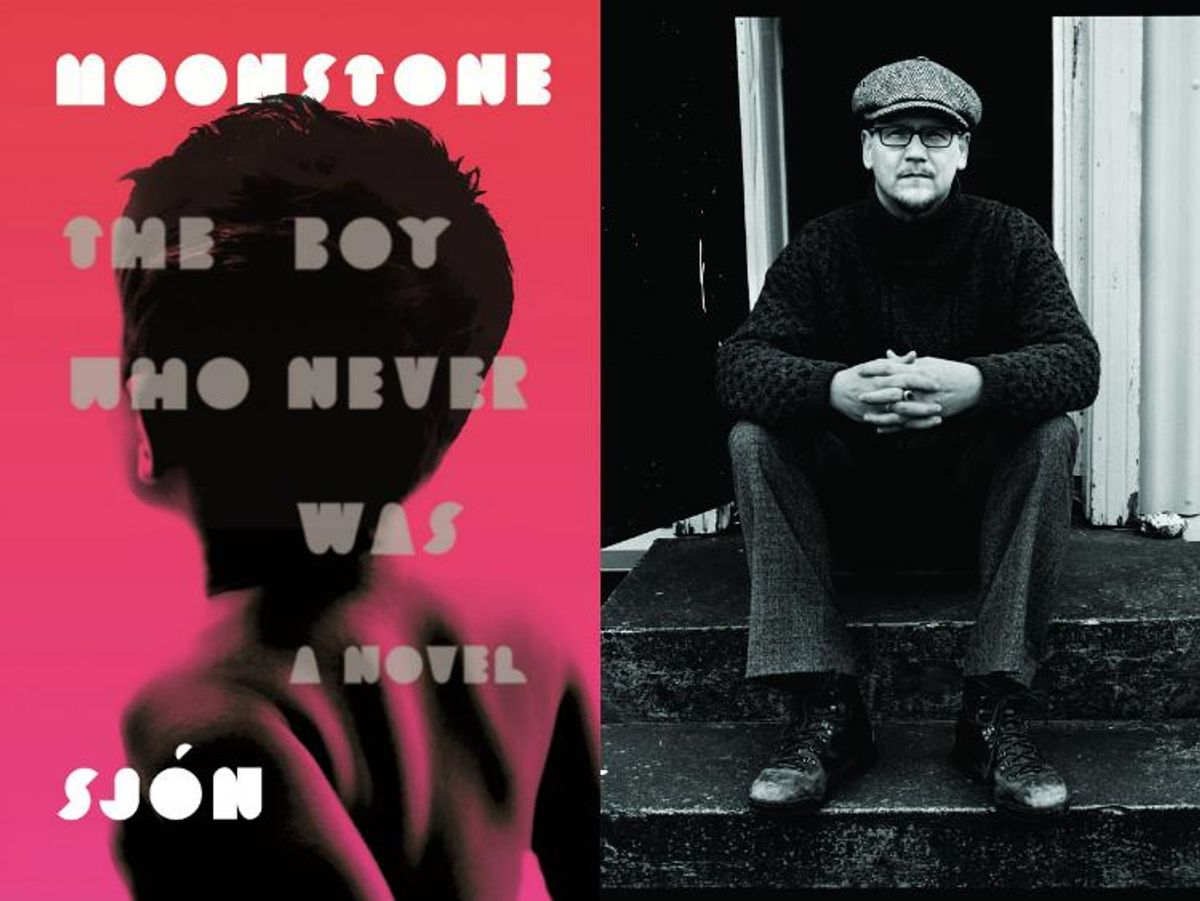

Thanks to the incredible praise given to his recent novel Moonstone: The Boy Who Never Was, Sjon is proving to be an important new voice in queer literature. His provocative novel uses its gay protagonist to explore the importance of cinema to achieve self-knowledge, while also offering a powerful revision of Iceland's unacknowledged LGBTQ history.

With a slightly psychedelic style that blurs reality with fantasy, Moonstone tells the story of a young gay boy in Iceland who, between cruising the town for sex and going to its two movie theaters, dreams of one day meeting the female star of his favorite film before a plague soon ravages the country.

Although Sjon does not identify as queer, Moonstone is nevertheless an incredible work of queer literature, acting as a cultural intervention into Iceland's forgotten and problematic gay past. Having grown up in the age of Andy Warhol and David Bowie, Sjon has adapted the attitudes of these gay icons into his own fiction, all in an effort to show that being queer can enrich the human experience.

Out: You've said you strongly identify with queer culture. What is it about queer culture that attracts you?

Sjon: When I was coming of age as young person involved in literature and music in the late '70s and early '80s, queer culture was a part of your required reading. To be in the know, you had to read William S. Burroughs and Jean Genet, watch the films of Derek Jarman, and be excited about Andy Warhol and his entourage of superstars. For me, the transgressive nature of their works was just very exciting. I drew energy from it in my own search for ways to challenge my surroundings. Queer culture today is at the forefront of exploring what it means to be human, how we can expand the human experience and our ways of living, and I am still being inspired by it.

As a teenager, you idolized David Bowie. Did Bowie have any influence on your novel and writing about queer identity?

I think my generation owes much to him. He put himself out there in his outrageous costumes and make-up and was ready to take on the ridicule it inspired. Simply by putting the question of gender and sexuality on the agenda with his queer personas, Bowie made it a part of your growing up to answer it for yourself and not to take it for granted that you were heterosexual. For kids living in a small city on the edge of the world, a place of about 85,000 people--where there were only two known "kynvillingar" [sexual deviants]--it was a big step toward liberation to be given license to be "special" by imitating and loving the androgynous alien Bowie projected.

You have written lyrics for Bjork--who you have also toured with--and Lars Von Trier. What was it like working as a songwriter with these two icons of music and cinema?

It was easy. I have known Bjork since we were teenagers, she was 16 and I was 19 when we met, and we spent years talking and arguing about the cultural movements we brought to each other's notice. To work with her is always a good opportunity for old friends to sit down together and continue a conversation that was started 35 years ago and produce lyrics on the side while we are at it. And I loved working with Lars. It was like a master class in filmmaking and I hope he took something away from it too.

For the main gay character of Moonstone, cinema provides an important escape from his harsh and lonely world. Why does cinema play such a central role in this young boy's life?

I think that in general cinema opens up new possibilities for the audience's self-exploration and self-understanding. The size of the images and close-ups of bodies in action make the experience irresistible. So, to be in a crowd but nurturing your own vision of what is going on in front of everyone's eyes, to secretly decode the glances, postures and touches of the characters, to have a crush on the actors and actresses in every possible way, that is cinema. By its nature, it is a sanctuary for all things queer.

What was the most challenging part of writing Moonstone? As a straight man, was it difficult to incarnate a gay 16-year-old boy as your narrator?

It was not difficult since we share much even though our times and sexuality divides us. I have been a 16-year-old, with everything it brings in growing up into a newly sexually awakened body and mind. And I was a film addict from a very young age. To imagine his clandestine relationships with the men of Reykjavik wasn't difficult either. It just came with the story and the ways it could play out in a town of 15,000 people were quite obvious. It was more difficult to write the intolerant society in which he lives into being without being judgmental.

The subtitle to your book is "The Boy Who Never Was." Do you think this reflects how members of the LGBT community can sometimes feel invisible or unacknowledged in society?

The title refers to the fact that until recently Icelandic members of the LGBT community have had no place in our nation's history--it is as if they never were. I was aware that on many levels it was a political act to write a queer main character into the narrative fabric of the days when Iceland gained its sovereignty. The new Iceland that was born on the first of December in 1918 was to be a strong masculine society that fed on misguided ideas about our Viking past. So it had no tolerance for limp-wristed ninnies. Luckily in the last three decades much has changed in the way we see each other and ourselves.

Your book blends different literary forms but ultimately ends with an emotional epilogue about your uncle who died of AIDS. Why was it important to end with his story?

When my uncle Bosi died I knew that one day I would write something that would honor his life. There was a feeling of debt and the need for some kind of justice to be done. And then it happened while I was writing Moonstone that I was finally writing that something for Bosi. The reverse mirror is that the book's description of a society ravaged by the Spanish influenza--where the queer character comes to the help of those who have ostracized him--holds up to the days when men who had been diagnosed as HIV or were suffering from AIDS-related complications were demonized. It felt right to state it clearly that behind this historical novel of a boy who never was there was also the story of Bosi and other men who did truly exist.

Purchase Moonstone here.

Nathan Smith is an arts and culture writer. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, TheAtlantic, and Forbes. Nathan tweets at @nathansmithr.