Entertainment

Mopping Drag Slang

Why we should stop using 'realness,' and start getting real...and other thoughts of a post 'RuPaul's Drag Race' world.

April 23 2012 9:51 AM EST

May 11 2016 2:32 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Why we should stop using 'realness,' and start getting real...and other thoughts of a post 'RuPaul's Drag Race' world.

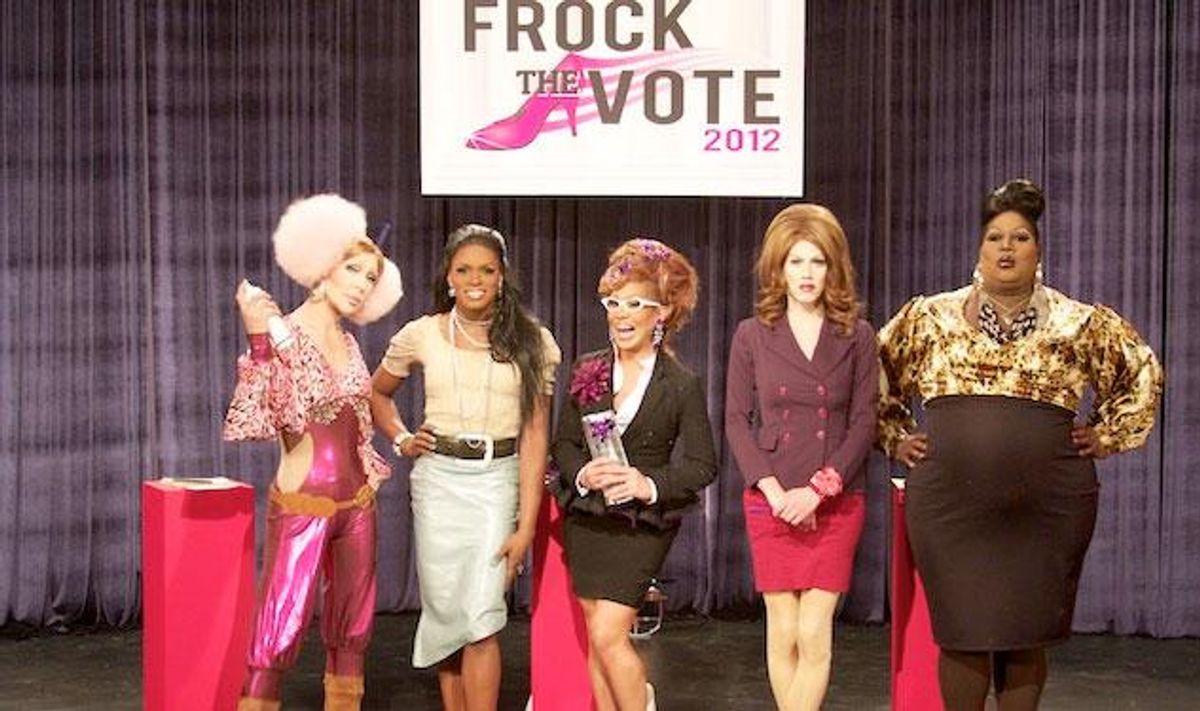

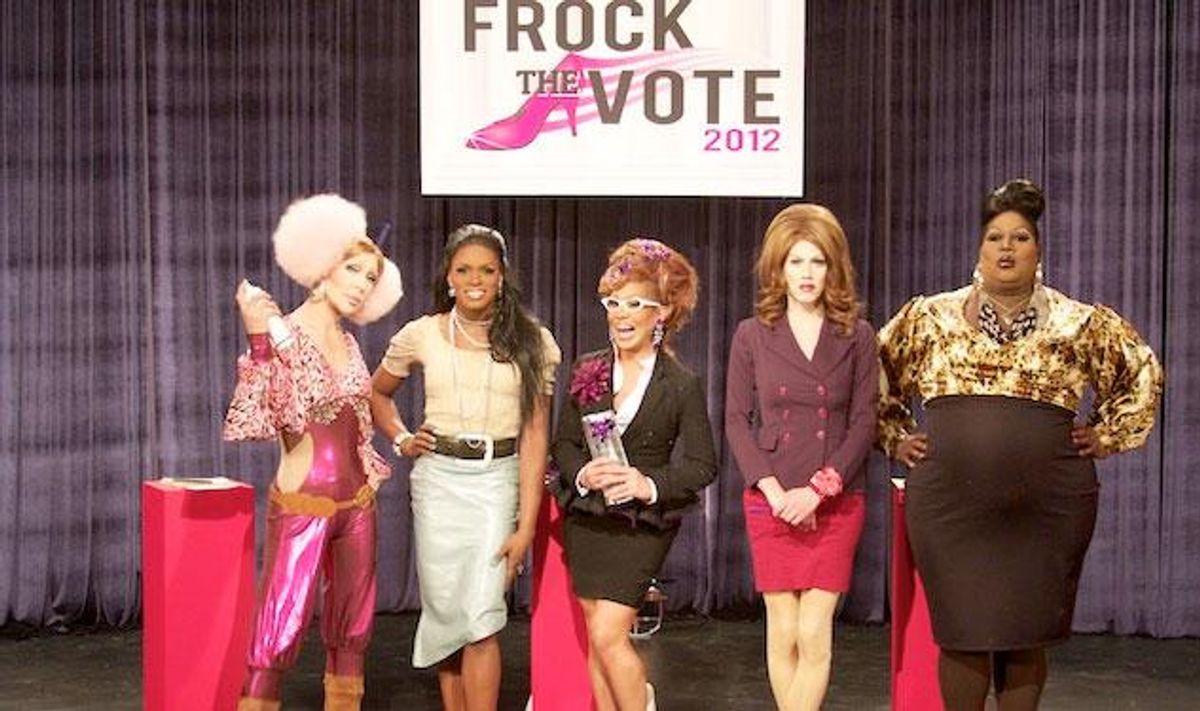

Photo of RuPaul's Drag Race courtesy Logo

A few weeks ago, the New York Timesreported that teenage girls are the most linguistically influential group in America. They add "like" to every sentence, and five years later, all of us do. They make everything sound like a question, and before you know it, even senators are upspeaking.

But while I respect the power of ninth grade girls, they influence me less than another group of fabulous ladies: Drag queens.

Specifically, I mean the queens on RuPaul's Drag Race. Those ladyboys have changed the way I speak, replacing my dried-up 90s slang with words like "fish" and "sickening" and "mop."

But why Drag Race? Why not imitate Jersey Shore or Real Housewives or Project Runway?

For one thing, drag slang is witty. Think about the acronym in "Charisma, Uniqueness, Nerve, and Talent." It's also evocative. If I dislike a queen's attitude, I couldjust say, "Phi Phi is a phony," but my feelings are clearer if I say, "The next time I see that Phi Phi bitch, I'm gonna read her for filth!"

And there are deeper reasons to appreciate the show's language.

Some of the terms have clearly been created for the cameras, or at least consciously reiterated for maximum TV impact. Shangela probably said "Halleloo" before she rolled into RuPaul's studio, but somewhere between wearing the corn-sage and popping out of the big package, she realized it was a viable catchphrase that could solidify her persona. "Halleloo" became part of her performance, and I respect her professional savvy in maintaining it.

And Shangela's just copying RuPaul himself, who dispenses trademark-worthy phrases like the Oscar Wilde of extended cable. He obviously knows that every "peek-a-Ru" extends his brand, and he knows that I know it, too. When I repeat his phrases (and Slate has compiled a list of Ru's most powerful catchphrases), I don't feel like a sell-out, but part of a self-aware game.

Then there's the show's othertype of slang--the kind that emerges naturally from the drag queen experience. When the queens say they're sickening or they're going to mop your purse or they ain't tryin' to have no kai kai in the dressing room, they're not branding a catchphrase. They're using that language because they're drag queens, and that's how drag queens talk.

Learning and repeating "real-world" drag language makes me feel connected to a purely queer universe--a universe that doesn't stop to see if straight people have caught up. Even in 2012, even as an out gay man who lives New York City and works in the theatre, I don't inhabit that space very often, but when I say "serving" and "fish," I feel a little more connected to the queer community and the series that celebrates it. My slang confirms my citizenship in queer culture, and when other people understand it, we can look at each other and feel connected.

In those moments, the lingo on RuPaul's Drag Race is more than a collection of awesome words. It's a vessel for belonging.

And yes, I know straight people watch Drag Race. But being gay makes me feel like I watch it better, like the show is mine.

That's a complicated feeling. After all, I don't actually belong to drag culture, and by using its language, you could argue that I'm stealing the words from drag's mouth. You could argue--and people have--that Drag Race and To Wong Foo and Paris is Burning commit cultural violence by turning the lives of underground queer communities into mass-market entertainment. You could argue that pushing drag into the gay mainstream, or even the American mainstream, destroys what made it meaningful in the first place. (Read Steven Thrasher's take on the current New York City ballroom scene, "Paris is Still Burning.")

Consider this: When he was researching a recent project, queer filmmaker and artist Wu Tsang encountered a Tumblr post that read, "99% of gay white males misuse 99% of the dialog from the film Paris is Burning. Stop saying Realness. #OccupyBallroom." That underlines the frustration in ballroom drag--typically a queer community of color. They create a world, and then other people twist it.

I called Tsang (who's work is currently on view as part of the Whitney Biennial and at the New Museum's triennial) to ask about the meaning of "realness," and he said it doesn't mean 'you look like a real woman.' It's more than that. "'Realness' is this really large idea of performing and being. Being is a kind of performance. It transcends any kind of cross-dressing."

I almost never use the word that way. When I wear a suit, I joke that I'm serving "executive realness," but I'm just talking about a costume, not my essence. That's a sin I commit against drag language, and I'm sure I commit others all the time.

But should that cancel my joy in speaking that way? Can I balance the positive and negative sides of appropriating words from queer subcultures?

I asked Tsang what he thought about the appropriation problem, and he said, "I feel 100% ambivalent about that. I feel like I see truths to both sides." He wrestled with the issue when he made the documentary Wildness, about a queer performance party he helped create in Los Angeles. Initially, the party attracted people of color, but as it got more popular, the audience grew, and some felt that bigger crowds ruined everything.

"I had this impulse to be politically righteous around that stuff and say, 'Well, this is a marginalized community and we need to protect it,' " Tsang said. "But actually that becomes paternalistic and kind of fucked up. It presumes there's some sort of culturally stable bubble world that has to be protected the way it 'should be,' versus constantly evolving and interacting."

Tsang noted that even though Paris is Burning, the landmark documentary about the New York drag scene, has a troubled legacy, it was a lifeline for him as a kid in rural New England. Likewise, I'm sure there's a lonely queer kid somewhere in America who's streaming Drag Race right now and feeling better about herself. In that sense, appropriation helps people.

And no matter what it's doing, appropriation is unavoidable. As Tsang sugested, unless you live in a bubble, you're going to interact with the cultures around you. Whether you're a teenage girl or a ballroom queen or a member of the Occupy movement, your language will never belong to you alone. Someone else will be moved or offended by it, or turn it into art.

And that's why I can't apologize for mopping drag slang. It inspires me. It makes my life better. Tomorrow, a German tourist may hear me say "serving" and take it to Cologne, and then I'll have been appropriated too.

However, even as I'm appropriating and being appropriated, I can be aware of what's happening. Staying mindful of where my slang comes from can remind me to respect any culture whose language is so strong that I want to learn it. Meanwhile, accepting that other people will borrow from me can remind me I'm not a loner, but a participant whose identity is constantly reforming. If I pick up "sickening" with gratitude and pass it on with respect, then maybe I'll feel more sickening as I make my voice heard.

Mark Blankenship is a culture writer in NYC. He edits the theatre magazine TDF Stagesand tweets as @IAmBlankenship. He works out to the song "Tranny Chaser."

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right