David Wojnarowicz. Two reasons you may not know that name:

--our culture can't remember, can't deal with, can't fathom the angry young man;

--it's too hard to spell (and pronounce).

Let's deal with the second reason first. Everyone spells it wrong. Forget it.

And the first reason, of course, is why you should know who David Wojnarowicz is. Where are all the angry young men? Contemporary life is not only culturally constrained, it is a compromise of privacy, of identity, of rage. We have to log on. We have to survive. Network, or perish. What happens to the fuming young artist who sledgehammers his dealer's wall? Who ditches his friends by the road in Nevada? Who marches in and takes paintings out of the exhibit? It's a romantic picture, the outsider, the rebel, but in reality, we are all too replaceable, too jaded, too doomed to wield our mallets. Or perhaps, we are too doomed to do it all the time. The anger that David Wojnarowicz channeled, his lashing, spitting invective against a life prescribed from birth, has become familiar, a mundane emotional disorder, easily treated by another prescription. Rage, at the governmental handoffs to hemorrhaging corporate behemoths, at the senseless cues of teleprompters, has become the dial tone of everyday life.

Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, by Cynthia Carr. Two reasons why it should be anticipated as the cultural biography of the year:

--sex isn't criminal;

--political art is not a compromised, twisting branch of art, rather, it is the truer art, while non-political art, art devoid of politics, is the poor sick offshoot of creativity.

1999. The New Museum hosted a retrospective of Wojnarowicz's work. Amy Scholder, his editor--first at City Lights and then at Grove Press--had worked on the catalogue, and was a year from releasing her third Wojnarowicz project, In the Shadow of the American Dream: The Diaries of David Wojnarowicz.

By ostensible measure, Wojnarowicz, 46 and relatively young, had cracked popular culture. But Wojnarowicz had been dead for seven years, and the aftermath of September 11, 2001, would put the country on a cultural course, literally, of zombies and vampires. In his early paintings, employing out-dated supermarket posters as his ground, Wojnarowicz satirized a contemporary ethos akin to the undead. "Scientists," Wojnarowicz told Carr, who wrote about and was consequently friends with the artist, "have discovered that if the head of a moth is cut off it can still continue to lay eggs. Somehow I don't think civilization is all that different... Society is almost dead and yet it continues reproducing its madness as if there were a real future at the end of its collective gestures."

The backstory of this difficult creative attitude is the stuff of Carr's first two hundred pages: the Dickensian upbringing that messed David up--foster parents, abusive father, flakoid mother, and years as a Times Square Hustler. Then, David as a young man, falling in love in Paris, obsessing over Arthur Rimbaud, and seeking to shock himself into a higher awareness. It is the biography's least scintillating stretch: Carr doesn't bring much life to Wojnarowicz's alcoholic father, who must have had something going for him to get all those women to fall in love with him--and while Carr does animate Wojnarowicz's mother, it won't be for another couple of hundred pages. But the promise of Wojnarowicz's future work, and the horrorshow of Wojnarowicz's personal catastrophe, push Carr into the glorious years of New York City's East and West Village: the sudden excitement of galleries springing up like mushrooms in a land that rich people had forsaken; the open spaces of big lofts and cheap rent; and the shame-free sexuality of city nights-- from the swaggering cruisers on the Hudson waterfront to the wife swappers at Plato's Retreat.

The backstory of this difficult creative attitude is the stuff of Carr's first two hundred pages: the Dickensian upbringing that messed David up--foster parents, abusive father, flakoid mother, and years as a Times Square Hustler. Then, David as a young man, falling in love in Paris, obsessing over Arthur Rimbaud, and seeking to shock himself into a higher awareness. It is the biography's least scintillating stretch: Carr doesn't bring much life to Wojnarowicz's alcoholic father, who must have had something going for him to get all those women to fall in love with him--and while Carr does animate Wojnarowicz's mother, it won't be for another couple of hundred pages. But the promise of Wojnarowicz's future work, and the horrorshow of Wojnarowicz's personal catastrophe, push Carr into the glorious years of New York City's East and West Village: the sudden excitement of galleries springing up like mushrooms in a land that rich people had forsaken; the open spaces of big lofts and cheap rent; and the shame-free sexuality of city nights-- from the swaggering cruisers on the Hudson waterfront to the wife swappers at Plato's Retreat.

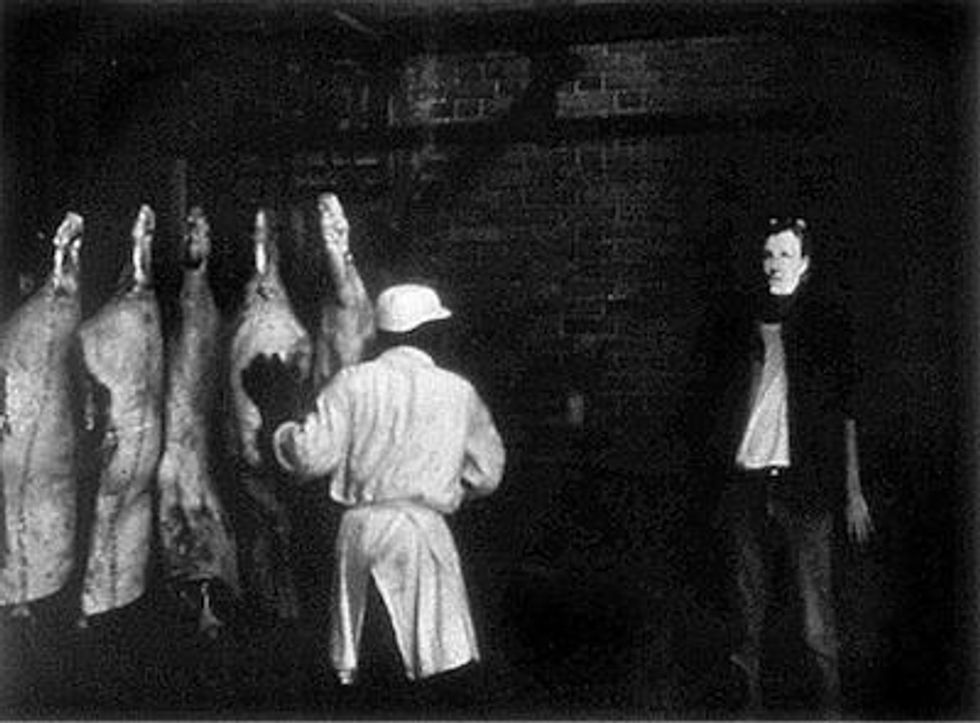

"Arthur Rimbaud in NY (in meat packing district)," 1978-1979. David Wojnarowicz. gelatin silver print

In the late '70s, Wojnarowicz moved from one New York City neighborhood to another, Hell's Kitchen to the East Village to Dumbo, fashioning himself a writer in the tradition of the beats (William Burroughs), evading work, and embarking on a series of photos, men in Rimbaud masks (sometimes sexual images, sometimes not), that would mark his metamorphosis; he was an artist willing to take on wildly disparate subjects, and to do it with paint, with photographs, with film, with performance, with sculpture.

Which leads to the other reason the first decade of the 21st century turned away from Wojnarowicz. There wasn't enough stuff to sell. Keith Haring's estate, to a lesser degree, faced the same problem. Curations of Haring's bigger scale works, on drop cloths and tarps, try to push the collectible object, but Haring is lost in the presentation. Haring would talk to you in the street, and marker a dog onto the cover of your new CD. That was the social revolution Haring was after. Infinite reproducibility. Which is, in a great irony, his saving grace in a market economy. Advertising. November, '86, Haring's major unveiling at the Whitney: Absolut Haring, an advertising campaign for the vodka. Andy Warhol had recommended Jean-Michel Basquiat for the gig, Basquiat couldn't make up his mind, and Warhol tossed it to Haring. In retrospect, we think of Haring and Basquiat as East Village personas. In fact, Basquiat and Haring, while they showed in the East Village, were standard bearers for Soho--Soho being Uptown's answer to a very dangerous threat to its hegemony, the East Village.

Writes Carr: "David complained that, during his first show, someone at the Milliken Gallery had said to him: 'Why can't you be like Keith Haring--full of fun?' David's work was full of sex and violence--politics expressed at the level of the body. He painted distress. Soldiers and bombers. Falling buildings and junkies. His images had the tension of some niceness opened up to its ruined heart. ... David would expose the Real Deal under the artifacts--wars and rumors of wars, industrial wastelands, mythological beasts, and the evolutionary spectrum from dinosaur to humanity's rough beast."

As the East Village community took shape--and it was a community, unlike the loose affiliation of enemies that constituted the 57th Street art scene--Wojnarowicz found a venue to show his work, and a support system to fabricate it. At that time, the challenges of process were significant, but the East Village's casual barter atmosphere allowed Wojnarowicz to get what he needed--art supplies to photographic prints. Carr's account would have benefitted from some additional context--at least to say collaboration was an active political statement, and creative model (last year, Alan Moore looked at New York collaboration, 1960s to '80s, in Art Gangs: Protest and Counterculture in New York City, released by Autonomedia). The East Village art experiment was consciously dismantling categories, redefining the artist, the critic, the art dealer. Concurrent to the East Village arts scene, an East Village literary scene was flourishing (check out Up Is Up But So Is Down: New York's Downtown LIterary Scene, 1974-1992, from New York University Press) and it's only an anachronistic mindset that allows a clear distinction. But if Carr doesn't make the argument, she provides the evidence; her portrait of Wojnarowicz and his circles is sensitive, unimpeachable, peerless, and in all likelihood the biography of the year. Fire in the Belly is an extraordinarily human account, and Carr achieves the rare and unique biographical ideal: time travel.

"Wojnarowicz Wall Drawing at Pier 34," 1983; color photograph by unidentified photographer

Perhaps the East Village was not Eden: drugs, crime, decay, and still, there was the egoism of artistry, the claims of origins and carping in the ranks. But the era was one of artistic freedom. Freedom, in the financial sense: artists were setting up studios for close to nothing, and for literally nothing in the thriving arts hive of the then abandoned Pier 34. Freedom, as well, in the collaborative sense--images were developed in a larger creative consciousness. Following Robin Winter's 1979 "The Dog Show," artists, including Haring and Wojnarowicz, looked to dogs as part of their visual language.

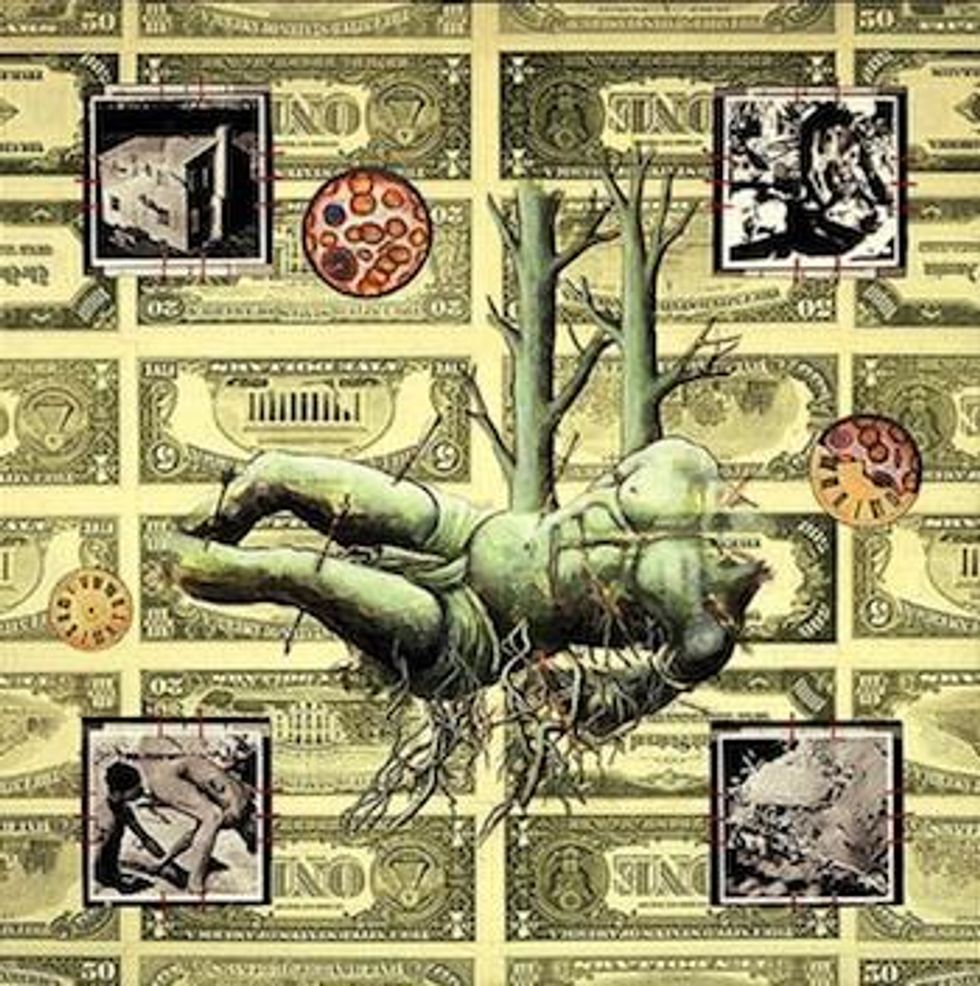

Animals, in particular, were a recurring theme: 1979's "Animals in the City," at ABC No Rio, returned for an encore engagement in 1980. Christy Rupp, the curator of "Animals in the City," contributed something of an overall aesthetic, which can be felt in Wojnarowicz's "cockabunnies" (cockroaches with rabbit ears and tails glued to them) and his iconographic puking cow. Haring's pigs recall the pig fixation of Debbie Davis (who Haring included in his Club 57 Twenty-five Artists show of 1980), and his aliens harken to the the aliens of Rich Colicchio, founder of the East Village gallery, 51X. Christof Kohlhofer's "25 Billion Dollars," which showed in the epochal 1980 Times Square show, is of a piece with Wojnarowicz's use of U.S. currency in the late '80s. The associations are seemingly endless, and invoke an artist's Canaan, and what might have been, had it not been for the mysterious "gay cancer" that first hit the news in New York in 1981.

For all its promise, the storm of excitement that swept over East Village art left little behind but rubble and the few successes who washed up in Soho. David was one of the successes, but his relationship to the more conservative Soho environment, which wanted paintings (and not particularly toothy ones), was tenuous, and he was emblematic of the East Village, which had become busied and hypocritical, and the target of a negative publicity campaign mounted by Soho. In the midst of what would later be called the AIDS crisis, the East Village wasn't capable of self defense. Wojnarowicz witnessed the death of many of his closest friends, among them his mentor, photographer Peter Hujar, who is best-known for his portrait, "Candy Darling on Her Deathbed," and emerged from his own diagnosis enraged, productive--his work defied the presumption that art is apolitical, that beauty is bald of activist consciousness.

(Pictured: Christof Kohlhofer's "25 Billion Dollars," 1980, wallpaper fragment from the Times Square Show)

Carr, in her evocation of Wojnarowicz as a mature artist, meets the high expectation of the artist's first full biography. The narrative of Wojnarowicz's struggle to remain sane, to make work, and to soldier against political factions determined to ignore, suppress, and do away with him, is as riveting and moving as Crime and Punishment, and as heroic and active as James Bond. In the midst of attacks on the National Endowment for the Arts (President Ronald Reagan had tried to abolish the NEA when he took office in 1980), which called out works by Andres Serrano, Robert Mapplethorpe, Annie Sprinkle and many others, Wojnarowicz contributed a text piece to Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, an exhibition curated by Nan Goldin for Artists Space. The essay "Post Cards from America: X-Rays from Hell," distilled Wojnarowicz's thinking on politics and arts, which he'd been working with as his primary subject matter since 1986. Wojnarowicz sought to personalize his political experience, and the essay is a tirade, but a justified one.

City, state, and federal government had massively failed to address AIDS, taking years to acknowledge that there was even a problem, acting with lackadaisical neglect on information it did have about the disease, and legislating (at least in New York) burdensome restrictions on testing. As late as 1985, New York's health commissioner, David Sencer, denied that there was a "crisis." The city, he told the San Francisco Chronicle, had done enough: "The people of New York who need to know already know all they need to know about AIDS." Everything, said Senser, was under control. Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., reported Randy Shilts in his 1987 book, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, "conservatives in the White House worried that people in the government should not be in the business of telling people how to have sodomy."

City, state, and federal government had massively failed to address AIDS, taking years to acknowledge that there was even a problem, acting with lackadaisical neglect on information it did have about the disease, and legislating (at least in New York) burdensome restrictions on testing. As late as 1985, New York's health commissioner, David Sencer, denied that there was a "crisis." The city, he told the San Francisco Chronicle, had done enough: "The people of New York who need to know already know all they need to know about AIDS." Everything, said Senser, was under control. Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., reported Randy Shilts in his 1987 book, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, "conservatives in the White House worried that people in the government should not be in the business of telling people how to have sodomy."

In his Artists Space essay, Wojnarowicz fantasized about dousing Senator Jesse Helms with gasoline and setting "his putrid ass on fire," and throwing Congressman William Dannemeyer off the Empire State Building.

(Pictured: David Wojnarowicz. Bad Moon Rising, 1989 Mixed Media.)

Since 1985, Congressman Dannemeyer had blocked AIDS education, sought to quarantine people with AIDS, and promulgated the science that "AIDS emits a spore that has been known to cause birth defects." As a publicity stunt for his soon-to-be released book attacking the gay rights movement, Dannemeyer read a ludicrous description of his vision of "What Homosexuals Do" into the Congressional record:

"Activities peculiar to homosexuality include: rimming, or one man using his tongue to lick the rectum of another man; golden showers, having one man or men urinate on another man or men; fisting or handballing, which has one man insert his hand and/or part of his arm into another man's rectum; and using what are euphemistically termed 'toys' such as one man inserting dildoes, certain vegetables, or lightbulbs up another man's rectum."

Wojnarowicz's essay went on to call Senator Helms "the repulsive senator from Zombieland," and dub New York's Cardinal John Joseph O'Connor, "the fat cannibal in black skirts." (Wojnarowicz had actually backed off on the Cardinal O'Connor line, having revised from the original "the fat fucking cannibal in black skirts.")

Various disclaimers, and Artists Space removal of NEA funds from the costs of producing the catalogue (Wojnarowicz wasn't in the gallery show), didn't deter the opposition from returning fire. The new chair of the NEA, John Frohnmayer, bungled the affair, caving to pressure to withhold the $10,000 NEA grant. The showdown was widely viewed as a test of the "Helms amendment," which enabled Congress to censor the actions of the NEA, and the NEA to decide (overseen by congress) what was obscene:

"None of the funds authorized to be appropriated for the National Endowment for the Arts or the National Endowment for the Humanities may be used to promote, disseminate, or produce materials which in the judgment of the National Endowment for the Arts or the National Endowment for the Humanities may be considered obscene, including but not limited to, depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts and which, when taken as a whole, do not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value."

In fact, the Helms amendment wasn't in play, because the grant had been awarded to Artist's Space in 1989, a year before the compromise was enacted, and the NEA backed down, shelled out, but a cultural war had been sparked, and Wojnarowicz was quick to understand the repercussions. Writes Carr:

"Few on the 'art' side of the culture war saw what was beginning here, while the far right found a uniquely exploitable world--skilled professionals making highly charged imagery that they could take out of context. The right wing frothers soon learned that--yes, nuance could be crushed, intimidation would work, and facts did not matter. Right-wing media would get the lies our unchallenged. ... Meanwhile, the Frohnmayers ... of the art world thought they could reason with the right, thought truth would change perceptions. They thought this was an episode, not the beginning of a train wreck. But David with his rebelliousness and his passion and his hairtrigger temperament and his illness that had made him even more sensitive to the total blockage in society--he got it immediately."

Social conservatism had adopted AIDS as proof of the sinfulness of homosexuality, but Wojnarowicz was unwilling to accept the presumption, and the sex and anger stayed in the work. "I don't think having AIDS is something heavy," Wojnarowicz told Rosa von Praunheim for his film Silence=Death, "it is the use of AIDS as a weapon to enforce the conservative agenda that's heavy."

As an emblem of what was wrong with the arts, Wojnarowicz continued to trigger salvos: in 1990, Reverend Donald Wildmon mounted a letter-writing campaign, xeroxing details from Wojnarowicz's works. (Wojnarowicz successfully fought back, issuing an injunction against Reverend Donald Wildmon and the American Family Association for violation of the New York Artists' Authorship Rights Act.) As recently as 2011, Wojnarowicz was in the news: after fielding complaints and fiscal threats from the Catholic League, Minority Leader John Boehner, and Representative Eric Cantor, the Smithsonian Institution removed Wojnarowicz's short film A Fire in My Bellyfrom the National Portrait Gallery's exhibit Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture.

But Wojnarowicz's larger contribution is not combative or controversial. In his work, he manages to summon, amidst all of the above, himself, a living man, with thoughts, emotions, memories and sexuality. Carr's biography performs the same miracle, tracking not only the trajectory of an artist who crossed paths with history, but a man whose boyfriend told him no, he could not take a dead vulture home in the car.

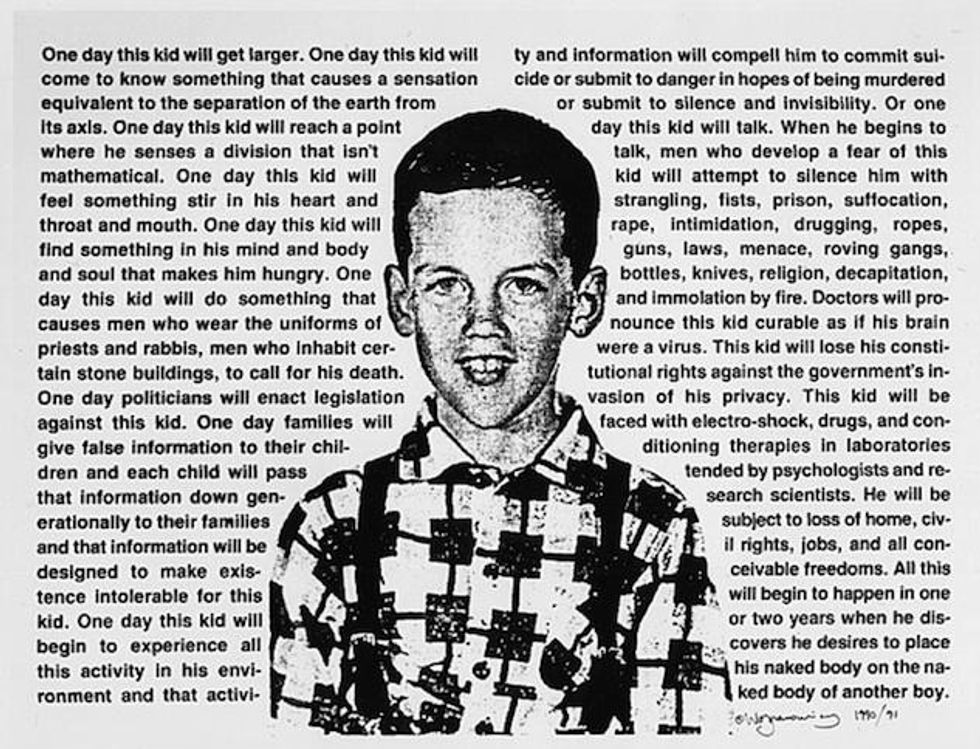

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One day this kid . . .), 1990. Photostat, 30 x 40 1/8 in. (76.2 x 101.9 cm). Edition of 10. Self portrait.

The backstory of this difficult creative attitude is the stuff of Carr's first two hundred pages: the Dickensian upbringing that messed David up--foster parents, abusive father, flakoid mother, and years as a Times Square Hustler. Then, David as a young man, falling in love in Paris, obsessing over Arthur Rimbaud, and seeking to shock himself into a higher awareness. It is the biography's least scintillating stretch: Carr doesn't bring much life to Wojnarowicz's alcoholic father, who must have had something going for him to get all those women to fall in love with him--and while Carr does animate Wojnarowicz's mother, it won't be for another couple of hundred pages. But the promise of Wojnarowicz's future work, and the horrorshow of Wojnarowicz's personal catastrophe, push Carr into the glorious years of New York City's East and West Village: the sudden excitement of galleries springing up like mushrooms in a land that rich people had forsaken; the open spaces of big lofts and cheap rent; and the shame-free sexuality of city nights-- from the swaggering cruisers on the Hudson waterfront to the wife swappers at Plato's Retreat.

The backstory of this difficult creative attitude is the stuff of Carr's first two hundred pages: the Dickensian upbringing that messed David up--foster parents, abusive father, flakoid mother, and years as a Times Square Hustler. Then, David as a young man, falling in love in Paris, obsessing over Arthur Rimbaud, and seeking to shock himself into a higher awareness. It is the biography's least scintillating stretch: Carr doesn't bring much life to Wojnarowicz's alcoholic father, who must have had something going for him to get all those women to fall in love with him--and while Carr does animate Wojnarowicz's mother, it won't be for another couple of hundred pages. But the promise of Wojnarowicz's future work, and the horrorshow of Wojnarowicz's personal catastrophe, push Carr into the glorious years of New York City's East and West Village: the sudden excitement of galleries springing up like mushrooms in a land that rich people had forsaken; the open spaces of big lofts and cheap rent; and the shame-free sexuality of city nights-- from the swaggering cruisers on the Hudson waterfront to the wife swappers at Plato's Retreat.

City, state, and federal government had massively failed to address AIDS, taking years to acknowledge that there was even a problem, acting with lackadaisical neglect on information it did have about the disease, and legislating (at least in New York) burdensome restrictions on testing. As late as 1985, New York's health commissioner, David Sencer, denied that there was a "crisis." The city, he told the San Francisco Chronicle, had done enough: "The people of New York who need to know already know all they need to know about AIDS." Everything, said Senser, was under control. Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., reported Randy Shilts in his 1987 book,

City, state, and federal government had massively failed to address AIDS, taking years to acknowledge that there was even a problem, acting with lackadaisical neglect on information it did have about the disease, and legislating (at least in New York) burdensome restrictions on testing. As late as 1985, New York's health commissioner, David Sencer, denied that there was a "crisis." The city, he told the San Francisco Chronicle, had done enough: "The people of New York who need to know already know all they need to know about AIDS." Everything, said Senser, was under control. Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., reported Randy Shilts in his 1987 book,