A new book argues that America’s most notorious hate crime was not a hate crime at all.

September 13 2013 10:25 AM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

aaronhicklin

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

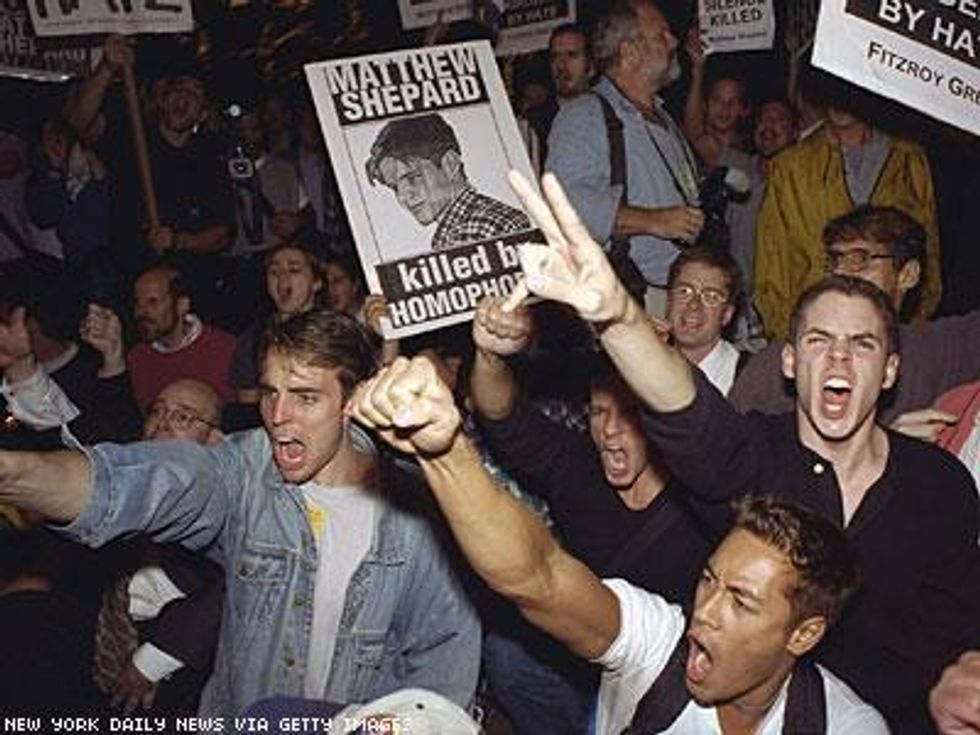

What if nearly everything you thought you knew abut Matthew Shepard's murder was wrong? What if our most dearly held assumptions about the circumstances of that fatal night, October 6, 1998, had obscured other, more critical, aspects to the case? How do people sold on one version of history react to being told that facts are slippery, and that just because we think of Shepard's murder as a hate crime does not make it a hate crime. And how does it color our understanding of a crime if the perpetrator and victim not only knew each other, but also had sex together, bought drugs from one another, and partied together? In short, has our need to make a symbol of Matthew Shepard blinded us to a messy, complex story that was darker and more troubling than the narrative we've come to believe?

None of this is idle speculation; it's the fruit of years of dogged investigation by journalist Stephen Jimenez, himself gay. In the course of his reporting Jimenez interviewed over 100 subjects, including friends of Shepard and of his convicted killers, Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, as well as the killers themselves (though by the book's end you may have more questions than answers about the extent of Henderson's complicity). In the process he's amassed enough anecdotal evidence to build a persuasive case that Shepard's sexuality was, if not incidental, than certainly less central.

Of course, none of what Jimenez discovered changes the fact that Shepard was horribly murdered, but what he discovers may change the way we interpret his murder. For many of us, after all, the crime was not simply one family's tragedy--it was a symbol to remind us that our progress in American society was far from secure, that in some quarters we were still hated, and that we should never take our hard-fought freedoms for granted. For many heterosexuals it was an equally profound reckoning that challenged the myth of America as a guarantor of equality and liberty.

All that symbolism and hand wringing may have felt necessary and cathartic, but was it helpful in getting at the truth? Where, for example, were the reporters five years earlier, when another gay man from Laramie--47-year-old Steve Hayman, a psychology professor--was brutally murdered and thrown off a Denver bridge into speeding traffic? What was it that was different about Matthew Shepard?

Add to that a President who needed to expiate his sins against the gay community--still recoiling from the double whammy of DOMA and Don't Ask, Don't Tell--and Matthew Shepard's posthumous status as gay martyr was sealed. The defendants didn't aid themselves by claiming they'd lured Shepard into their car and then flipped out when he came on to them. The chief witness for the prosecution, McKinney's girlfriend, Kristen Price, reinforced that narrative in court.

But in what circumstances does someone react so violently that they would slam a seven-inch gun barrel into someone's head hard and often enough to crush his brain stem? That's not just flipping out. That's psychotic--literally psychotic to anyone familiar with the long-term effects of methamphetamine. In court, both the prosecutor and the plaintiffs had compelling reasons to ignore this thread, but for Jimenez it is the central context for understanding not only the brutality of the crime, but the milieu in which both Shepard and McKinney lived and operated.

McKinney had been on a meth bender for five days prior to the murder (a detail originally reported by Wypijewski in her 1998 Harpers story and much expanded on in Jimenez's book), and spent much of October 6 trying to find more drugs to keep him going. By the evening he was so wound up that he attacked three other men in addition to Shepard. Even Cal Rerucha, the prosecutor who had once pushed for the death sentence for McKinney and Henderson, would concede that methamphetamine played an outsize role in Shepard's murder. "It was a horrible, horrible, horrible murder," he told CBS's 20/20 in 2004. "But it was a murder that was driven by drugs."

WATCH: Jimenez Discuss Matthew Shepard Case

No one was talking much about meth abuse in 1998, though it was rapidly establishing itself in small-town America as well as in gay clubs in big metropolises where it would soon leave a catastrophic legacy. In Wyoming in the late 1990s, eighth graders were using meth at a higher rate than twelfth-grader nationwide. Sources told Wypijewski that meth was everywhere. It's hardly surprising, then, to discover that Shepard was also a meth user, and--according to some of his friends--an experienced dealer who had fallen in with a group in Denver.

From there it's not much of a stretch to imagine how Shepard and McKinney, both in their way lost, young men, might have been familiar to one another long before the night in question.

In spite of his interviews, Jimenez does not entirely resolve the nature of their relationship. McKinney presented himself as a "straight hustler" turning tricks for money or drugs, but others--including a high-ranking officer in the Albany County Sherriff's office--characterize him as bisexual. A former lover of Shepard's confirms to Jiminez that Shepard and McKinney had sex while doing drugs in the back of a limo owned by a shady Laramie figure, Doc O'Connor. Another subject, Elaine Baker, tells Jiminez that Shepard and McKinney were friends who had been in sexual threesome with O'Connor. A manager of a gay bar in Denver recalled seeing McKinney and Russell from the papers and recognizing them as patrons of his bar. He recounts his shock at realizing "these guys who killed that kids came from inside our own community."

Not everyone is interested in hearing these alternative theories. When ABC's 20/20 engaged Jimenez to work on a segment revisiting the case in 2004, GLAAD bridled at what the organization saw an attempt to undermine the notion that anti-gay bias was a factor; Moises Kaufman, the director of The Laramie Project, denounced it as "terrible journalism," though in fact the segment went on to win an award from the Writers Guild of America for best news analysis of the year. (In Jimenez's book several witnesses also interviewed by Kaufman's Tectonic Theater Project for his play suggest that inconvenient truths were edited out of their stories in the interests of making a political statement).

There are valuable reasons for why certain stories need to be told a certain way in pivotal times, but that doesn't mean we have to hold on to them once they've outlived their usefulness. In his book <Flagrant Conduct>, Dale Carpenter, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, unpicks the notorious case of Lawrence v. Texas, in which the arrest of two men for having sex in the privacy of their bedroom, became the vehicle for affirming the right of gay couples to have consensual sex in private. Except that the two men were not having sex, and were not even a couple. As Dahilia Lithwick, writing about Carpenter's book in <The New Yorker>, concluded "The dirty secret was that there was no dirty secret." Yet this non-story, carefully edited and taken all the way to the Supreme Court, changed America.

In different ways, the story of Matthew Shepard that we've come to know and embrace was just as necessary in shaping the history of gay rights as Lawrence v. Texas. It helped galvanize a generation of LGBT youths into action, and stung lawmakers into action. President Obama, who signed the Hate Crimes Prevention Act, named for Shepard and James Byrd Jr., into law on October 28, 2009, credited Judy Shepard for making him "passionate" about the issue of LGBT equality.

There are obvious reasons why advocates of hate crime legislation must want to preserve one particular version of the Matthew Shepard story, but it was always just that--a version. Jimenez's version is another, more studiously reported, account, but he is not the only writer to challenge the popular mythology. Wypijewski was the first journalist to reject what she called the "quasi-religious characterizations of Matthew's passion, death, and resurrection as patron saint of hate-crime legislation" in favor of what she called "wussitude"--a culture of "compulsory heterosexuality" that teaches young men how to pass as men, unfeeling, benumbed, primed to cloak any vulnerability in violence.

It was Wypijewski, also, who wondered if Kristen Price--the star witness--simply thought she was helping out her boyfriend when she told the press that he and Henderson "just wanted to beat [Shepard] up bad enough to teach him a lesson not to come on to straight people." If you thought that gay panic was a better defense than a drug-fuelled rampage, wouldn't you perhaps go with it?

Jimenez is less interested than Wypijewski in that kind of social analysis, but what's striking all through this book is how desperate McKinney is to refute allegations that he is gay or bisexual himself--even at the expense of undermining his own case. Whether it was a hate crime, a drugs crime, or a combination of both, it's hard to shake the suspicion that self-hate, and a misguided culture of masculinity--which taught McKinney to abhor in himself what Shepard had learned to embrace--was as complicit as anything else in the explosion of violence that robbed Shepard of his life.

That is, of course, a kind hate crime--just not as straightforward as the version we've embraced all these years.