In a new memoir, Sean Strub — the founding editor of POZ — recalls his time in the forefront in the fight against AIDS.

January 10 2014 9:00 AM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

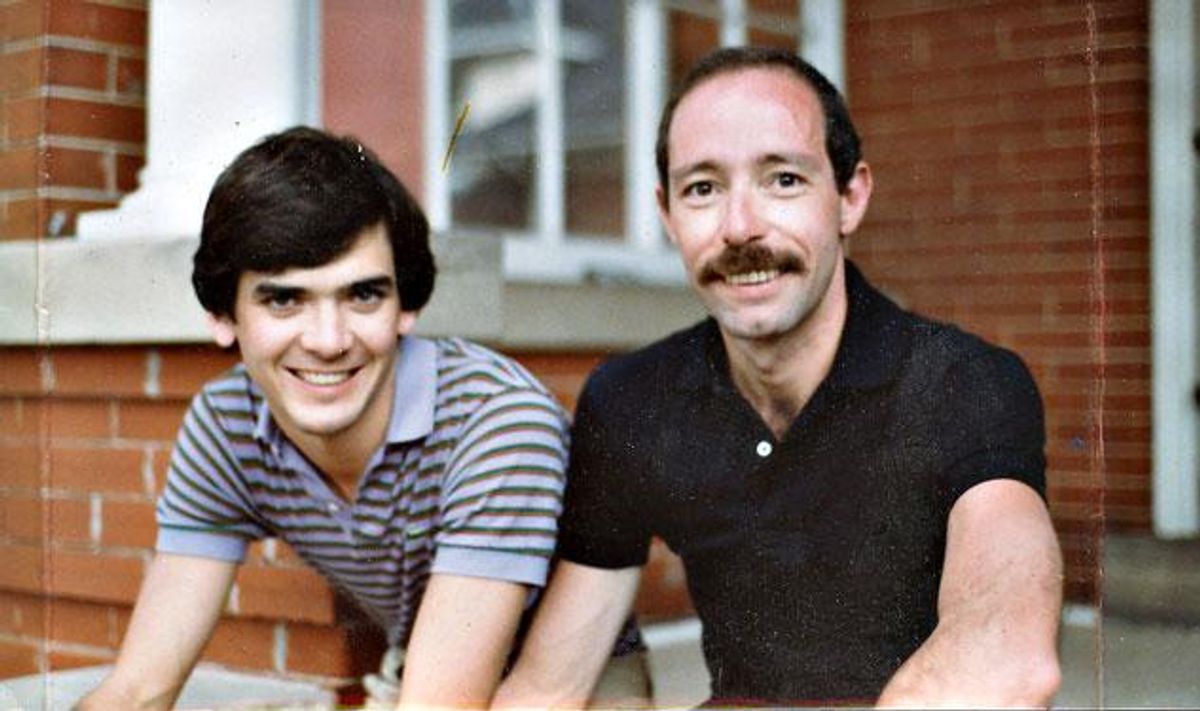

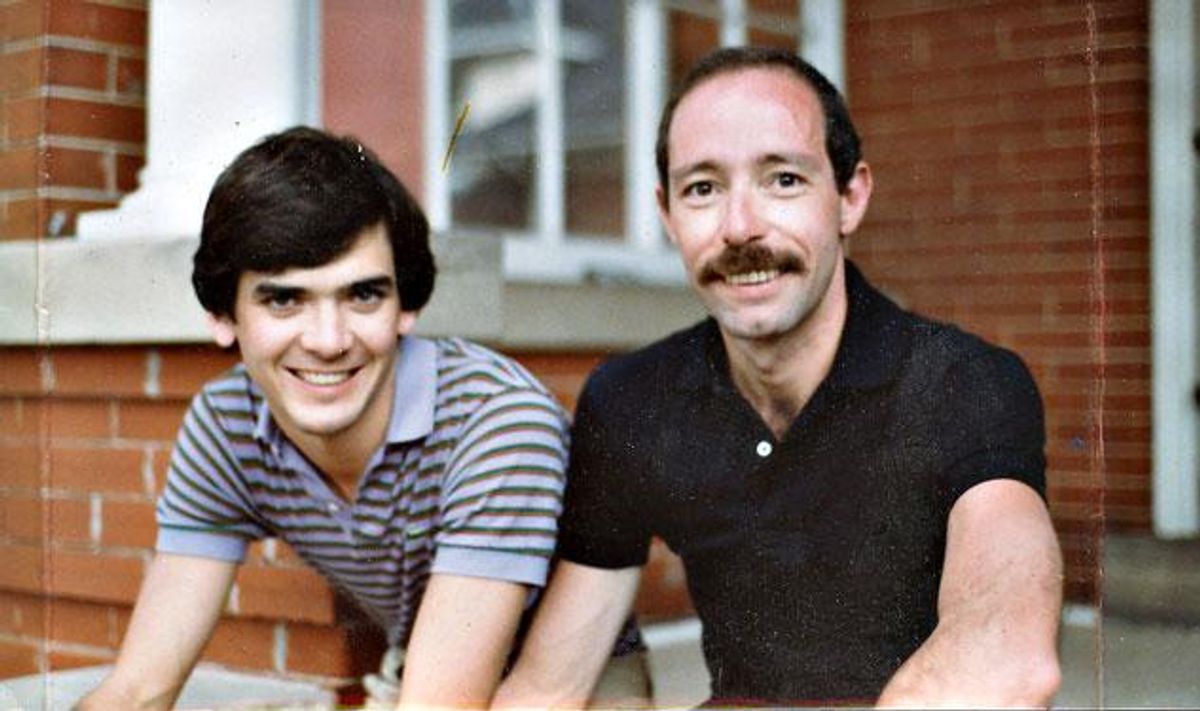

The two men in the photo above had just spent the week snuggled up in a single bed at a mutual pal's house in Denver, becoming fast friends as each turned an important corner in their young careers.

Sean Strub, left, had for the first time been hired by a political campaign even after telling the boss he was gay, a bold declaration encouraged by Vito Russo, right. Copies of Russo's book, The Celluloid Closet, had just arrived via a new service called FedEx.

It was a good day, and they were a little stoned, loose and affectionate. Strub said, "If I had to die when I was young, I would want it to be at the end of a day like this." Russo, struck by the sentiment, recorded the quote in his journal.

It was June 5, 1981 -- the same day on which the Centers for Disease Control published its first report about a rare kind of pneumonia found in five Los Angeles gay men.

AIDS would eventually touch every angle of the two men's lives and work. Russo helped found GLAAD, which devoted much of its early work to calling out homophobic coverage of the epidemic. He died of AIDS in 1990. Strub tested positive for HIV in 1985 and parlayed his experience with political fundraising into amassing donations that helped create and sustain organizations from AIDS Medical Foundation to ACT UP. He later founded POZ, a monthly magazine that blended treatment updates with sumptuous portraits and profiles of HIV-positive people. He fully expected to die within months of its launch.

He didn't, and in his new book, Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS, and Survival, Strub proves to be a rare breed of narrator, one who weaves a rich tale that both predates the early crisis--he arrived in Washington, D.C., in 1976, still swooning over Carter's liberal optimism even as gay politicos clutched tightly at their closeted power--and managed to survive its darkest days.

"I write pretty quickly, but I'm a polemicist, not a memoirist," says Strub, whose book comes in at 410 pages, a hefty but compelling read. "I started out knowing memory could be unreliable, and discovered exactly how unreliable. I wake up in a cold sweat every other night thinking of things I forgot to put in and people I forgot to mention."

Now 55, Strub welcomes the recent surge in AIDS histories--he appears in most documentaries of the period, including 2012's VITO and How to Survive a Plague -- but cautions that it's easy, with the most acutely painful days in the past, to succumb to nostalgia. "I fear that activism has been kind of romanticized," he says, "and [we are left with] this belief that it started with ACT UP."

Strub's focus -- in the 1980s and in the book -- sits squarely on the grassroots HIV-positive folks who organized support groups, buyer's clubs, and treatment information newsletters. And he's vocal about acknowledging a deeply held divide between institutions such as Gay Men's Health Crisis and the sex-positive community activists -- later embodied by the defiantly queer ACT UP poster-boy types -- who resisted much of the immediate, panicked conventional wisdom that gay men must be celibate or commit to lifelong condom use.

Three decades into surviving, Strub sees the stigma of having HIV -- like the rates of new infections among gay men -- getting worse. "When someone tested positive 15 or 20 years ago, there was a loving LGBT community that took on this epidemic as a shared responsibility, that put their arms around you and said, 'We will get through this together,' " he says. "Young gay people often don't know anybody -- or don't think they know anybody -- with HIV, and the LGBT movement has largely left AIDS behind.

"There's a real sense of not wanting people to forget and yet being surrounded, particularly in gay culture, by a world that has forgotten. There is a kind of compulsion to tell that story, and as time passes there are fewer and fewer around who can speak first hand."

In POZ -- which has now existed for 20 years, long after Strub stepped away -- there is still an emphasis on a healthy skepticism of medical authorities and the fundamental, once-radical assumption that if you believe you can survive, you will increase your chances of doing so. For a decade, Strub published his own lab charts in the magazine, soliciting often contradictory advice from doctors and other practitioners. He also oversaw a strict policy that only HIV-positive people would grace its glossy cover. This month, for the first time, it will be his own face staring out. "I have to tell you, I'm excited," he says. "I'm that somebody out there who finds out they're going to be on the cover of POZ."

Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS, and Survival, is available Jan. 14