Ahead of his company’s 30th anniversary season in New York City, choreographer Stephen Petronio relives his wild ride in a new memoir.

April 07 2014 11:10 AM EST

November 02 2015 9:59 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Ahead of his company’s 30th anniversary season in New York City, choreographer Stephen Petronio relives his wild ride in a new memoir.

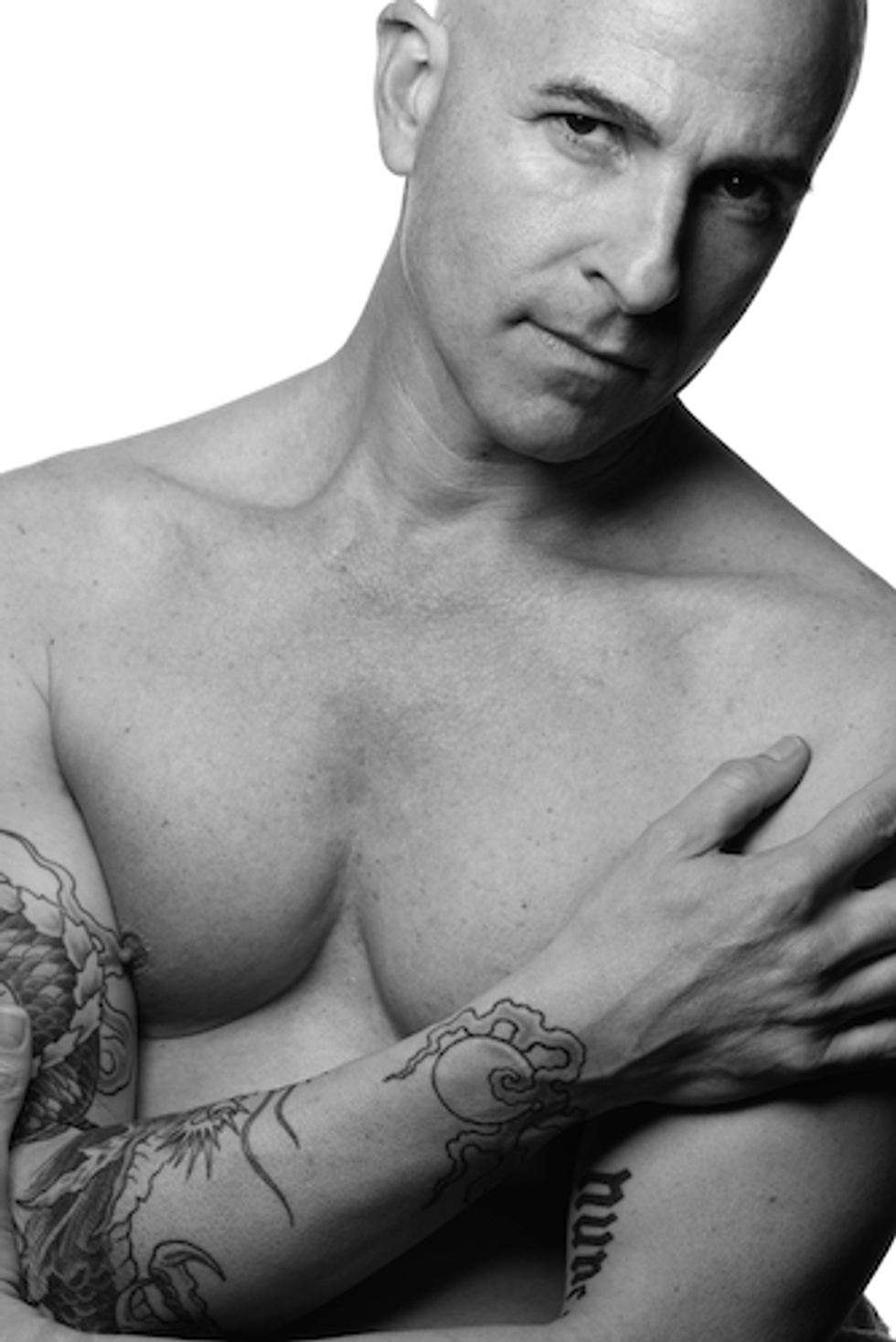

Stephen Petronio Company: Nick Sciscione (left) & Joshua Tuason | Photography by Sarah Silver

When we first meet Stephen Petronio in his new memoir, Confessions of a Motion Addict, he's in London in 1989 suffering from a serious hangover. The playback from the night prior looks something like this: coke, ecstasy, whisky, wine, coke, sex, blackout. The following morning, in search of coffee, he's arrested for wearing a lewd Vivienne Westwood T-shirt and cheekily defends himself in court to the amusement of the crowd. His point is clear: Dancers can be rock stars, too.

For the past four decades, Petronio has been a staple of the New York dance scene--initially as the first male dancer to join the post-modern pioneer Trisha Brown's company, and later as the director of his own troupe. This week, the Stephen Petronio Dance Company celebrates its 30th anniversary at the Joyce Theater (April 8-13), remounting past works and premiering a few new ones (coincidentally, Brown's company is performing a few blocks away as well).

It's an impressive milestone, and Petronio has distinguished himself along the way with a singular brand of whipping limbs, urgent leaps, and proud eroticism. His is indeed the work of an addict (hence the title)--fetishizing speed, hungry for more, at home in the dark, lusty corner of the club where anything goes.

"Everybody's addicted to something," Petronio writes, not for the first time, in his book. "I love these addictions like old friends. For better or worse, they belong to me."

In Motion Addict, Petronio takes bold ownership of his demons and presents a raw portrait of the artist as an unapologetic thrill-seeker. For the childhood portion of his story, Petronio paints a warm, albeit hectic, picture of an extended Italian-American family in 1960s New Jersey. He's a self-proclaimed mama's boy; his relationship with his father was a mix of respect and intimidation. Like many male modern dancers, Petronio discovered movement in college and fell under the tutelage of post-modern luminaries like Steve Paxton and Lisa Nelson before making his way to New York in 1978, where dance became his life.

But sometimes you get an uncomfortable feeling that actual people seem to matter less than substances and physical release (whether on stage or in bed). For example, we're told of the impressive circumference of 20-year-old Jeff's penis and how, on Petronio's first international tour, an unsuccessful sex session was salvaged when a bottle of body oil was found in the bathroom. But of his two marriages to two women, we are told almost nothing. The effect of this imbalance of details is that hook-ups feel more meaningful than marriages.

Even a seven-year relationship (a monogamous romance during the disorienting early years of AIDS that Petronio credits with likely saving his life) is given an unceremonious dismissal: "I'm also single after seven years with Justin Terzi and enjoying it." The breakup comes out of nowhere, with no explanation of cause or exploration of feelings, just moving on.

The most jarring example, however, is with his daughter, who Petronio decided to have with a female friend in 1989. "But she's another story," he writes of his daughter, and that's the first and last we hear of her. We're shown a picture of his 2010 wedding to husband Jean-Marc Flack but never hear the details of that day or how it changed him or his art. (The book, however, is dedicated to both husband and daughter.)

Like Petronio's choreography, the chronology and thematic organization of the memoir careens all over the place. In his dances, this is thrilling; on the page, it's confusing. Because the book is written in the present tense, you're always in the moment, but not always sure which moment: East Village in 1978 or London in 1992 or back to New York in the '80s. Or simply "one year later" in Putnam County. It's as if Petronio's experiences all took place at once--and are all still happening. In other words, it feels like Petronio is reliving his life (mainly the most exciting, extravagant parts) rather than reflecting on it.

At one point, when describing a heroin binge and questioning a codependent relationship, Petronio's writing slips--accidentally, it seems--into the past tense: "I'd been so in love, obsessed with Michael... But in the end I couldn't trust what was between us. Who knew what either of us really felt, or for that matter who we really were. We were too high to decipher."

Why he decided to alter the otherwise consistent verb tense of his prose here is unclear. But the passage allows for distance and a sense of true internal searching that is lacking elsewhere: Finally, the motion addict pauses. It's refreshingly revealing and, consciously or not, gives haunting weight to this moment and this man.

Sometimes Confessions of a Motion Addict, despite its title, feels more interested in shocking readers than moving us. There's an impulse to pose to Petronio the same questions he asks of Michael: But what did you really feel? What do you regret? What did you learn? The glorification of his binges and short change given to supposedly significant people in his life (wives, husband, daughter, the dancers who realized his vision for three decades) makes it difficult to decipher.

Whether this is a reflection of the man or simply a reflection of the book, we don't know. Still, the memoir is ultimately, and commendably, an honest portrayal of Petronio's obsessions, all of which have contributed to his dances--dances that are rightly celebrated as visceral, ravenous, and riveting.

Stephen Petronio Company's 30th Anniversary Season, April 8-13 at The Joyce Theater, NYC

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right