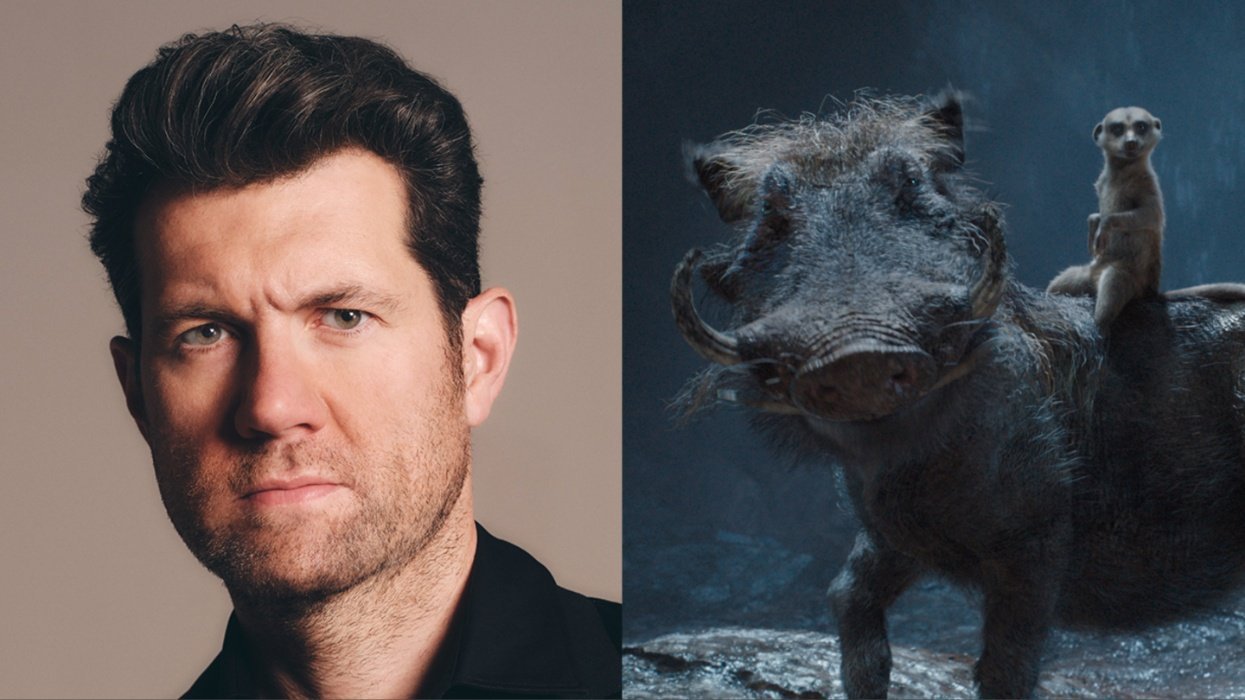

Photo by Jason Bell for the 2009 Out100

Tony Kushner was one of Out magazine's first OUT100 honorees 20 years ago, in the inaugural edition of our annual, celebratory portfolio. An emerging playwright, Kushner was neck-deep in the buzz surrounding Millennium Approaches, part one of his AIDS-themed stage epic Angels in America, which had just debuted on Broadway. Often put in the same arena as Larry Kramer's The Normal Heart, Angels likewise shook the zeitgeist in how it viewed the epidemic; however, it aimed for vastness in both theme and scope, and eventually became a stirringly literate "fantasia" on so many facets of the gay experience: social, political, spiritual, sexual, existential, and, indeed, medical.

In the years since, Kushner won a Pulitzer for the play, has been nominated for multiple Oscars, collected countless theater accolades, made musicals, and collaborated with the likes of Steven Spielberg and Maurice Sendak. He even made the jump to TV, turning Angels into a hugely lauded HBO miniseries with the help of director Mike Nichols. He's now partnering with the network again for a forthcoming, very hush-hush series, as well as working with Jeanine Tesori (Caroline, or Change & Fun Home) on a new musical production.

Punctuating Kushner's achievements have been more OUT100 hat-tips (in 2003, 2004, and 2009, to be precise), which were highly deserved for a man so uncannily skilled in articulating artful critiques of society. Kushner knows Angels has had a profound impact on many (including yours truly), but when we recently met for a lengthy coffee date to look back on his work, he said it's the responses to his other projects that can truly lift him up.

Out: So take me back to 1994. It was the first year you were featured in the OUT100, and Angels in America had just made its Broadway debut the year before. What's it like to be in the wake of such a tremendous passion project?

Tony Kushner: I don't think it was so much of a passion project. It was a play--my second professional play [after A Bright Room Called Day], and I really approached it like that. I was commissioned by the Eureka Theatre to do a play for them, and when I started working on it, I was in my early thirties. But by the time I had finished the first part, Millennium Approaches, I began to get the sense that there was something about this play that had not been true about [Bright Room]. The minute I sent copies of the first draft to people, there was an immediate excitement about it. New York Theater Workshop gave me space for the first reading of it, and we did a workshop production of it around 1989 in LA. A couple of months later, the National Theatre in London called and said that they wanted to do the play.

And this was still just for Millennium Approaches?

Yeah, I had only barely begun work on part two, Perestroika. By the time the first production of part one opened in San Francisco, it was already running in London, and Ian McKellen talked about it on the Tony Awards, and Frank Rich wrote a rave review of it in the Times. And he hated my first play. So this kind of crazy thing started. The interview that I always remember is one with Susan Cheever, [author] John Cheever's daughter. I can't remember what publication it was for, but it was one of my first profiles, and we spent a few hours talking. I think it was even before part one had opened on Broadway. At the end of the interview she said, "Congratulations," or something like that, and I said, "We'll see." And she said, "You don't realize what's happened yet. Your life is completely different now. Even if you didn't do a good job on the rest of the play, you've moved to this very rarified category, and you're going to be operating on a very different set of terms, in terms of your long-term career." This is what I remember her saying, and I found it kind of shocking. I didn't really believe it.

And after that?

In the years since, I realized that she was sort of right. It just took a while for it to catch on. It's very disorientating--I couldn't believe that it was becoming the thing that it was becoming. The openings of parts one and two were both featured on the front pages of The New York Times and it was on NBC Nightly News. It turned into this sort of gigantic cultural phenomenon for a while. Mark [Harris, Kushner's husband] always says that celebrity and success is basically a character test. I think that's true, and I think I did pretty well. I didn't get crazy, I didn't stop working, I didn't freeze up, and I didn't go out and buy, you know, 95 expensive automobiles, and become bankrupt and go to Hollywood and start writing bad action movies. But it was really an overwhelming and strange time. I keep a journal but I've never had the nerve to go back and read what I wrote about during all that. I'm not sure what I'm afraid of exactly, but there's something that makes me hesitate.

I kept a journal in my early twenties, during the time I was coming out, and it's loaded with dialogue from Angels in America. It came into my life just when I needed it--the HBO miniseries, not the play. I get what you meant about it not being a "passion project," per se, but it's admittedly odd for me to hear that, since I always envisioned Angels as something that just poured out of you.

In one sense it did just pour out of me, and things rarely do. I wrote the first draft of Perestroika in 10 days. It was, like, 700 pages long. I couldn't stop writing. I would try to go to sleep and I would wake up two hours later. But I was a lot younger then--I couldn't do it now. When I say it wasn't a passion project it's because that term seems, to me, to always be something separate from what you do for a living. And I've never written anything that I didn't care about emotionally--not just because I'm an emotional person, but because if I can't find something that's deeply moving to me, I become the dullest person on the planet. I have to care about it a lot to access any talent I have, otherwise, I just become sort of like a block of wood. At the time, if I had thought, you know, I'm going to write the thing that I'm going to be remembered for and it's going to win all these prizes, I don't think I would have written a word of it. I'd have been too frightened. But I had a number of things that I know I wanted to address, and I was writing it for a theatre company in San Francisco, so it was a really good time to write about being gay, and that was part of the permission.

Images from the 1993 production of 'Angels in America' with Stephen Spinella and Joe Mantello

I'm going to leap ahead to 2003, which was the second year you were featured in the OUT100, and the year of your Angels HBO adaptation, among other projects.

That was a really exciting time for me. My play Homebody/Kabul, which I had been working on in 1997, was in rehearsal just before, in 2001--it was in rehearsal at the New York Theatre Workshop when the towers came down, and it was my next full-length play after Angels. It made its own kind of noise, and it was touring and produced in various other countries. Meanwhile, [composer] Jeanine Tesori and I were working on Caroline, or Change, the first musical theater piece I had written, and I was having what, I think, remains the most pleasurable creative experience of my entire life. I'm madly in love with Jeanine and I come from a family of musicians, so in some ways that piece was the most autobiographical thing I'd ever written. That was between 2003 and 2004, and right around that time, I had just written a book, Brundibar, with Maurice Sendak, and Homebody/Kabul came back to New York with Maggie Gyllenhaal starring in it. So there was a ton of stuff going on, then in the middle of it, HBO did Angels.

What was the most surprising thing about the Angels phenomenon, including its migration from stage to screen?

The thing that I didn't expect, which almost started to happen immediately, was that the play began to get taught in a lot in colleges, and I feel like a substantial part of its still healthy, ongoing life is that it seems to work really well as a text for reading--it's had a real life among college students. It was pretty much being done all over the world before Mike Nichols first asked if I would be willing to let him do a film version of it, and also, in the years between that and the Broadway debut, I worked for several years with Robert Altman on a film version. Bob and I both decided finally, and mutually, that we weren't going to do that. He's a great artist, and he sort of redefined what "epic" meant in modern American art, but I think it was not meant to be.

The concept of Robert Altman's Angels in America conjures up all sorts of thoughts.

You know, he had some really interesting ideas and then some really strange ones. I began to get the feeling that the way he worked was incredibly improvisational and to move the amount of story that you need to move to keep the play coherent, it was just not going to happen. And then there was no one else I really wanted to let make this into a movie and I was going to let it go. I never thought of someone like Mike, and then he called and said, "Can we meet?" Working with him was an incredible education and a great thrill. It was the perfect way to be inaugurated into the world of filmmaking, which I knew absolutely nothing about. And given Mike's immense talent in theater as well as film, he really wound up being the perfect person to do it. He said that what people always do is make the mistake of feeling that you have to open out the play to make it a film, and in doing that, you destroy the essential claustrophobia of the theatrical event. That's a great phrase, and I think he's dead right about that.

I never saw the Broadway production of Angels, but I loved that the film retained stage-centric things like having actors play multiple characters.

I asked him, "Why do you want to do that?" And he said, "I want to see Meryl play a rabbi!" But I think the real reason was that he got that it was a way of preserving some of the theatricality and it was, you know, a failed illusion--one that's almost successful but not completely successful, so you can experience it but have skepticism at the same time. I had watched a lot of the filming, and I knew that a lot of the stuff was astonishing, and that the acting and the cast were so great. But I was still terrified. I remember HBO did this big fancy premiere at the Ziegfeld, and it would be the first time an audience had seen it. On the way, I was just complaining on and on in the back of the limo with Mark, and finally the limo driver turned around and was like, "Look if you hate this so much, why don't you get another line of work?!" But then the movie took off.

Another milestone in 2003 was your commitment ceremony with Mark Harris. It was first time such a thing with a gay couple was published in The New York Times' Vows section. That's a pretty historical moment.

Yeah, that meant a lot to people, more than we realized it would. We just sort of said we'd do this because we thought it would be a hoot, and they called us and asked us if we'd be in the front for our announcement. People still come up to me with a copy, or a laminated copy of the photograph.

Have you laminated it?

The Times sends you a laminated copy. We don't have it hanging anywhere or anything, but the woman who wrote the piece did a beautiful job, and I think it just meant a lot to people that it was there. You know, my father is in the picture, in the background, smiling. He's very loyal to his family. But when he got back to Lake Charles, a cousin, this asshole, came up to my father and said, "I saw that picture of you in the Times, and boy, do you look uncomfortable." My father never spoke to him again.

What are some things about Mark that enrich you as a person and an artist?

Mark and I first met in 1997 and, he's the absolute perfect husband for anyone involved in the arts, especially in theater or film, because he's got such incredible clarity about what matters and what doesn't. He knows how to make the distinction between what you want as an artist and the blur of media hyperactivity that surrounds everything that happens. It's there in the way he writes about the Oscars, which I think is so wonderful. He loves all of it for what, at its best, it can be: a kind of national expression about thinking about film. And he's completely unmoved, and unsentimental, and dismissive, or even condemnatory of the part of it that turns filmmaking into a blood sport. He's less of a theater person than a film person, but he he keeps track of everything, and he had the same kind of clarity about theater--what you need to listen to and pay attention to, and what you don't.

Over the years, every time I've listened to him, I've been very glad, and every time I'm having a hard thing to handle it's been a godsend to have him here to bounce things off of. And the times I haven't listened to him--and there haven't been many--I've really regretted it. He's been a kind of reality principle for me.

A scene from 'Lincoln' starring Sally Field and Daniel Day-Lewis

Caroline, or Change premiered on Broadway in 2004, the third year in which you were featured in the OUT100, and then Munich opened in theaters in 2005, marking the first part of what would become a very fruitful relationship between you and Steven Spielberg. This seems like it was a major transition period for you.

HBO's Angels had gotten me Kathleen Kennedy, Spielberg's producer, who called me for a breakfast meeting to see what I was doing. And I said to her, "What are you guys doing?" I thought I'd do the Angels film and then go back to theater, and Kathy said, "Well, we're doing two movies--one about the murder of the athletes at the Munich Olympics and the other about Abraham Lincoln." I wound up doing both movies, but Angels kind of made the connection with Spielberg.

I did the first draft of Munich, and I wouldn't let him pay me for it. I wanted to do it on spec, because if I know that if there's some huge check in my bank account that I have to somehow earn, it would frighten me and I wouldn't be able to write a word. I wanted to be able to fail because I'd never written a [theatrical] screenplay. So I sent him a 272-page first draft, which seems brief compared to what I went up to with Lincoln, which was 500 pages. When I finally worked on Lincoln, I think the whole time I was writing it I was like, He's never going to film this. This is some weird exercise in I-don't-know-what and he'll say, "Thank you very much." And that will be that.

So, 2009 was the most recent time you were part of the OUT100, and you were probably very deep in the Lincoln zone at that point. What else was happening in 2009?

I was doing a season of plays at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, and I had written The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures. The weird thing about that was that I was working on Lincoln the whole time, and I kept thinking I'm going to stop working on Lincoln and I'll have time to go work on it later. But I started working on Lincoln in 2005 or 2006, and it took maybe four years to get to the first draft. I just couldn't find a way in, or which part of the story I wanted to tell to make it into a feature-length film. It was so overwhelming that I kept delaying starting work on [The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide...], and then I finally had to ask Michael Greif to direct it, cast it, and design it without a word of the script. Soon I got the Lincoln script down to 250 pages, and Spielberg gave the script to Daniel Day-Lewis. We had to go to Ireland to meet [Day-Lewis] and have a lot of discussions before he finally said yes.

What are you up to now?

I'm working on an adaptation of a big, sort of famous German-language play, but I can't say which one. And it may be for a big star, but I can't say whom. It's for Broadway, and I recently finished the first draft. I also just finished the second draft of the new movie that I'm working on for Spielberg. It's based on this work of history, The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, by David Kertzer, about the kidnapping of a Jewish child by the Vatican in 1858 in Bologna, Italy. I thought it was going to be easy because it's this incredibly exciting story, but I sort of overlooked the part where you have to make a dramatic account of something that American audiences--or most people on the planet--know nothing about, which are these stories of the unification of Italy in the middle of the 19th century. So it's been harder than I realized. Then I'm working on an HBO series--which I can't say anything about except that it's an original idea and it's contemporary--and I'm developing a new musical with Jeanine Tesori about the death of Eugene O'Neill.

One thing I've tried to do--and perhaps failed to do in this interview--is not tie you too tightly to Angels, simply because it means such a great deal to me. But, thinking of the arc from 1994 to 2014, it did bring you a lot of things, and, as you said, the film brought you a lot of things. When you truly reflect, do you think of it as being the work, or just another work?

No, I mean, it's certainly the thing that I'm known for. I do always get very happy when anyone comes up and says, "I really loved Caroline," or, "I really loved Homebody/Kabul," or, "I really loved The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide." But mostly its Angels in America this or Angels in America that, and I'm fairly certain that when I die my obituary is going to say, "The author of Angels in America." But I kind of knew at the time that it was going to be a non-reproducible moment--one of those things where I wrote the right play for the right moment, without really realizing or being conscious of what I was doing, and so this sort of astonishing thing happened. And if I felt that I was going to have that happen every time that I wrote I would never write again. And I think, certainly, Lincoln was a big deal. It got me to the White House and I got to have dinner with Barack Obama, and I was very, very happy.

I feel like I've had other successes and it would be depressing if everything after Angels sort of disappeared. Still, I don't think anything is going to mean quite as much as that meant, to a great deal of people. If something else hits big, great, but that's never my job. The minute I start to think, Oh, this is going to be big, or, This doesn't feel big; why am I doing this, I'm finished as a writer.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right