Interviews

WATCH: 'We Steal Secrets'

Alex Gibney's documentary unravels the mystery behind Bradley Manning, Julian Assange, and the trouble with WikiLeaks

May 23 2013 6:06 PM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

jerryportwood

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

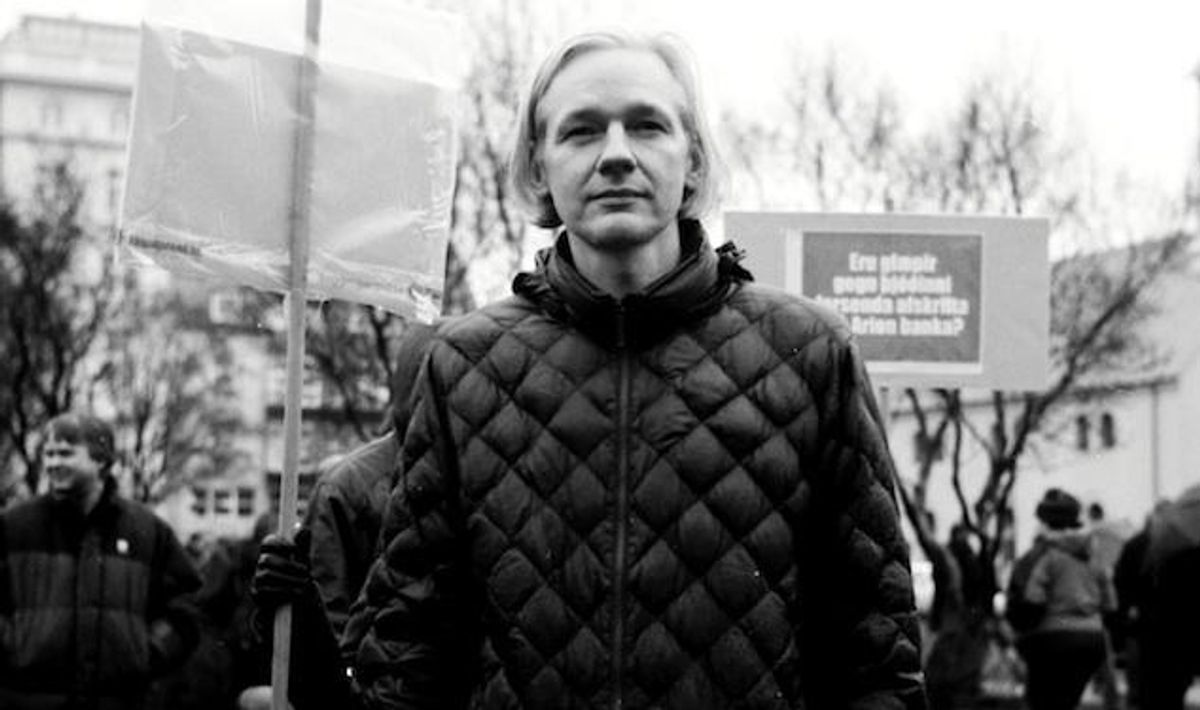

Pictured: Bradley Manning caught on camera at a Boston party in a clip from 'We Steal Secrets'

Perhaps you think Julian Assange is a freedom fighter at the center of a grand global conspiracy dedicated to crushing him as he battles for truth. Or Bradley Manning is not a heroic whistleblower, but a disgrace to LGBT people. No matter what notions you bring to the table, Alex Gibney's startling documentary, We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks, applied nuanced analysis to a complicated web of intrigue, intelligence, and personalities. Although WikiLeaks founder Assange appears to be the star of the film, it is the information that Gibney is able to cobble together concerning Bradley Manning's history that enlightens a story just weeks before he goes to trial.

We caught up with Gibney before the May 24 theatrical premiere of the film to find out if he thinks Bradley Manning is a hero (not exactly), if he's ready for the hostility the film will undoubtedly receive (perhaps), and how he got Lady Gaga to give permission for him to use "Telephone" in a pivotal moment of the film (he wrote her a letter).

Out: So many of us think we know this story, understand it and views of what side of it we're on. open up that conversation again, are you worried that people are dogmatic about who is a hero and who's not and will come after you?

Alex Gibney: Well some have already. I'm not so worried about it. I want to engage that. In a lesser way that's what the film is about. It's saying, "Don't believe everything that you read. And what's the Dylan line, "Don't follow leaders, watch the parking meters." Blind faith is not a good thing. Trust but verify.

Looking at WikiLeaks, I had a similar feeling to what was going on in the organization of what was going on in the Catholic church when I was working on that documentary. The idea of the church saying, there's so much that we do and it's good, so these scandals that involve priests abusing children, just give us a break. Who said that one had anything to do with the other?

That's what I thought was great in the film, that you reinforce that the Bradley Manning issue is different from the Julian Assange issue. The WikiLeaks case is different from Julian's personal life as well. There are obviously many stories, but it's mainly two stories you're telling here, right?

I wish there were only two! But yes, it's two stories really. At its heart there are two characters, Bradley Manning and Julian Assange. When I started, it was only about Julian. Bradley Manning was a character who had been shunted into the wings, and it seemed more appropriate to bring him center stage, particularly now with his trial coming up in a couple of weeks.

That's some of the most heartbreaking stuff. We've had access to his online chats before, but the way you and the team animated those, putting the text of the sentences on the screen. I had a strangely emotional reaction that I wasn't expecting.

We discovered the same thing in the cutting room. This guy Tim Webster, the army counterintelligence guy that Adrian Lamo went to, he said this interesting thing when I talked to him. He said Lamo is very charismatic online. That through typing and the text that you enter into a computer, that you can perceive that kind of charisma--it mada me think, We're now talking to each other increasingly through text, so why shouldn't Bradley Manning's texts be presented online? And with Andy Grieve, my editor, and Will Bates, the composer, we found a way of making that come to life. It's powerful and emotional even though it's text.

That's another of the messages that you're making sure people understand: It's not just secret dealings and hushed conversations. Two people, Adrian and Julian, manipulated an idealistic young man through their chats.

And when we're typing stuff down, sending texts or emails to each other, we forget how not-private that is. Even when we post stuff on Facebook, we think, Oh yeah, that's sort of private. It turns out it's the most public possible thing, after all, the government is hoovering up all that data in case they find a key word that they can use down the line. It's a peculiar kind of isolation and intimacy and this sense of privacy: Typing by yourself at a computer feels alone and private. Everything you type is probably public in some shape or form.

No, I don't know any journalist has met Bradley Manning face to face. I'd like to.

But you said not having access to them gave you the freedom to explore in a new way. Can you explain what you mean a little more?

Sure, I can't remember exactly if it's Andre Gide, who said, "Art is born of constraint and dies of freedom." Sometimes having constraints ends up pushing you to do interesting things in a film that you otherwise wouldn't do. In case of bradley manning, we couldn't interview him, but we had these chats, particularly when the second batch came out. There was a lot missing and when Wired released all of the, or all that we know about, it gave a much well-rounded portrait of the man. We decided to use those chats. It seems obvious now in the movie, but it didn't seem obvious at the time. We were terrified: How can you put that much print on the screen? We decided to embrace it.

On the other hand, with Julian, we were trying to convince him to talk to us from the beginning of the film all the way until the end. But at some point I sensed, even if he did talk to us, he wasn't going to be able to take us back to a moment prior to the release of the Afghan War Logs. When he was not so famous. When he was not so much a kind of spin doctor, always thinking about soundbites the way a politician does. They aren't talking to you, they are talking to hear that echo off a wall. What was that Julian Assange before that? How could we present that. We dug back deep into some of the earlier conversations.

Then I got in touch with this filmmaker, Mark Davis, who had made a pretty good film about Julian. He had just followed him around. To be able to use that footage--not as cut-up clips but uninterrupted with all its pans and swoops--it conveyed that idea of an "itinerant hobo," as Davis said, wandering the world with his laptop, trying to right wrongs. It was before all the fame had hit and was surrounded by lawyers and agents. Finding Mark and interviewing him so he could give us perspective on that moment was terribly important. You get this cinema verite feel inside this larger film which was an important moment.

You also see the idealism turn. Some people are going to have conspiracies and think this was doctored or manipulated, but are you hoping people can keep an open mind and understand that Julian Assange is complicated, a man of many things. He did become a rock star to many, but he wasn't so bad at the beginning.

That's absolutely right. That's absolutely what I want people to think. [Guardian journalist] Nick Davies says it at some point: There was an aspect to this guy that was great. Then there was this other side.

Maybe I misinterpreted this, but there seem to be a moment near the end of the film that implies that Bradley Manning was communicating directly with Julian Assange, and if he is being accused of aiding the enemy, the only "enemy" he ever collaborated with was Julian Assange. Is that correct?

I wouldn't necessarily put it that way, but I think it's fair to say that at the very least Bradley Manning thought he was conversing directly with Julian Assange. And I think he was. I don't see anything wrong with that from a legal perspective but it does get to the heart of this idea of this whole electronic dropbox. It's an important contribution, the New Yorker just got one that was designed by Aaron Swartz, but I think that section of the film is saying is that a relationship, a human relationship, is important too. If WikiLeaks had maintained that relationship with Bradley Manning, he might not have needed to go to Adrian Lamo. Those chats come from evidence that the U.S. government has and released at these pre-trial hearings. [Bradley] refers often to speaking with Assange. And Assange says, "Lie to me." Which I also found powerful moment. It's a double-edged moment. All that is meant to convey something important about this source-journalist relationship. It's not just mechanical. It's not just about dropping something in a dropbox, it's a human exchange that has a lot to do with trust.

Of course we see those in the Lamo chats, he says, I'm going to give you this journalistic protection, tell me what you want. and then he turns on him.

He does, he betrays him.

Adrian is a difficult character for us to relate to as well. Perhaps that is partially due to his "being on the spectrum," or whatever it is, his personality quirks. But at the end, seeing him cry was such an unexpected moment. How did you react to that moment?

It was unexpected and I don't know exactly what to make of it. I included it with that in mind; I don't expect the audience to know exactly what to make of it. But he's crying, he's experiencing some kind of anguish for doing what he did, for being in the situation he found himself in. It's not so simple. It turns out this stuff is tough. It doesn't boil down easily to political posterboys.

I know that your producers working on the film went through own change of heart during the making of this documentary. With this politically and emotionally charged material, was there ever a moment you thought, let's not pursue this? How do you remain dedicated to a project when you know there will be such hostile reactions?

I hope all the tough decisions are made early on. I hope people examine the risks up front and know they are determined to see it through to the end. All the people here were committed, including the funder. This is an unconventional funder for this type of a project, Universal Pictures, and now being distributed by Focus World. You know, they were tremendously supportive and did not interfere at all.

Of course you were able to keep a distance, but so many people will continue to wonder, is Bradley Manning a hero, is Julian Assange a hero. Do you hope the film helps people think outside of those binaries and see them in a new way?

I think it does help people. I think people come in to the film thinking that Julian is a perfect hero. And I think they leave thinking he's an anti-hero. I think Bradley Manning, let's face it, is not a perfect person. But he is also not a stick figure or political caricature. He's a human being with a lot of flaws, but I do think what he did, in some fundamental way, is heroic. I think that's how I'd like people to see it. People want to turn things into a simple thumbs up, thumbs down experience. Everone has to wear a white hat or black hat so you can make up your mind and move on.

And, let's not forget, you were lucky enough to have Lady Gaga on the soundtrack...

[laughs] Look, she was very generous. The way it works, you go out to people and say, everyone is going to get paid the same. But there are a lot of themes that I think people are going to respond to. I wrote her a letter and she related and allowed us to license the her music.

It's actually a really great moment, I started smiling. I needed that.

It is a great moment! Bradley Manning was listening to "Telephone," by the account of his chats. It is a great moment, and then it cuts to Julian dancing in the disco. It's one of my favorite moments in the film.

Watch the We Steal Secrets trailer below:

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays