Photographed by Roger Erickson for Out.

Last year, Aubrey Allicock played the role of gay boxer Emile Griffith in Champion, Terence Blanchard's opera-in-jazz, in St. Louis. A Tuscson native of Guyanese and African-American descent, Allicock has since graduated from Juilliard's top-tier program for opera singers, and performed in productions of Rinaldo and Alice in Wonderland. This fall, he makes his debut on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera in a new production of The Death of Klinghoffer.

Directed by Tom Morris (War Horse) and composed by John Adams (Nixon in China, Doctor Atomic), The Death of Klinghoffer is based on the 1985 hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro by Palestinian terrorists, which resulted in the killing of a wheelchair-bound Jewish passenger, Leon Klinghoffer.

Since its premiere in Brooklyn in 1991, the work has drawn praise and criticism for its libretto, which some Jewish organizations have called anti-semitic. While this new staging hasn't failed to anger protesters outside Lincoln Center, Allicock, who plays one of the Palestinian terrorists, tells us why Klinghoffer should be required viewing, regardless of where one stands on current affairs.

Out: The Death of Klinghoffer marks your stage debut at the Met. How are you feeling?

Aubrey Allicock: I worked at the Met back in 2010 as an understudy, but this is my first time singing on the stage. Surprisingly, I feel really comfortable. I know the music because I've sung the role before for six productions of Klinghoffer. I know what my voice is able to do with it, and I'm actually finding myself being able to explore my character further. It's more about being more comfortable with the character--because the music is no problem.

How did you prepare for the role of Mahmoud?

I read the ship captain's memoir, in which he describes his peculiar relationship with Mahmoud on the Archille Lauro. There's one instance when Mahmoud is listening to music from his country on a radio. He gets happy and he starts to share this music with the captain in his broken English, translating the lyrics from Arabic to English. The captain [writes] that he felt like he was with one of his kids. Adults don't usually appreciate the same music. You listen to it, and you pretend to be interested just to keep them happy. Through doing that, and opening a little bit of yourself, you find common ground. [The captain and Mahmoud] connected on that level, and saw eye to eye at least on something during this terrible event.

Did you have a personal issue with playing such a controversial character?

The two other lead cast members were attacked on their Twitter account. Some people wrote on their wall: "You've been marked for life"; "We'll never forgive you for doing this"; "You're a terrorist." I don't have a Twitter account, so I haven't been targeted. Because I'm seasoned in this role, I'm looking for a deeper angle than, "I'm a terrorist." Out of the four hijackers, Mahmoud is much more the philosophical, emotional one. During his first aria, he explains to the captain how he grew up. His first toy was a real gun. His mother was killed, and his brother was decapitated. This is how this person was growing up. He doesn't know anything else but war. His AK-47 is his first love. In his culture, his gun makes him a man, it's a weird rite of passage.

Apparently, most people who criticize the opera claim that they haven't seen it in its entirety...

In this staging, the part of Omar, one of the terrorists, is sung by a woman who is Israeli. She used to be an Israeli soldier, and in this production she plays a Palestinian woman. This is conflicting for her as well, but not in the way of people who haven't seen the opera and calling it 'trash' and 'terrible.' It's completely different for her.

Some cast members also switch parts across the opera: They play both crew members on the ship and Palestinians, correct?

We do it because it's our job, this is what we're taught to do as an opera singer: You throw yourself into a role. For any actor, no matter how tough it is, you need to know how to open yourself up, push everything aside, and actually take that role on, and do the best you can at it.

One interesting fact is that Alice Goodman, who wrote the libretto, was Jewish and converted to Christianity while writing Klinghoffer...

One can never know what she was really going through during that time, but I find that very interesting. There are some things in the libretto that are definitely a nudge at one religion or the other, but it's definitely telling the story of the hijacking, and what happened.

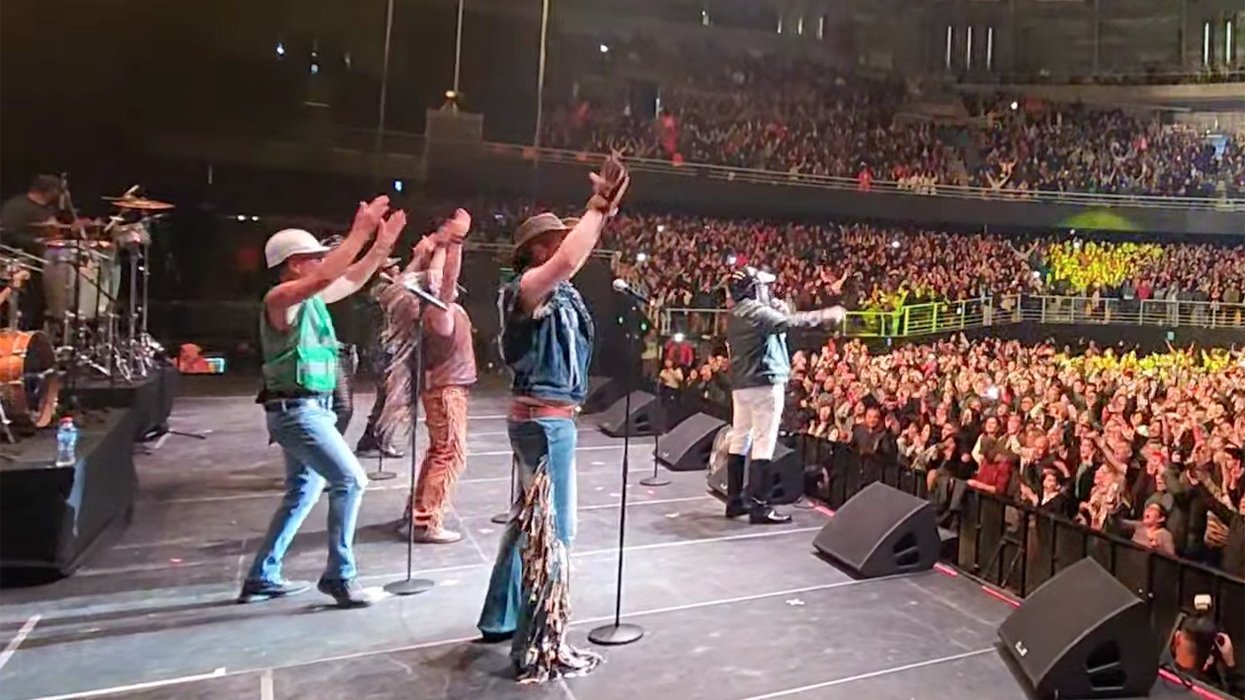

From Left: Aubrey Allicock (Mamoud), Paulo Szot (Captain), and Sean Panikkar (Molqi) in The Death of Klinghoffer | Photo: Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

At one moment during the opera, the captain says to Mahmoud: "If you could talk like this, sitting among your enemies, peace would come." What would you tell those who criticize Klinghoffer to "make peace?"

First of all, I would tell them to actually watch the production. I know most of them have read the libretto, but it's only one thing to read the libretto. Sometimes, reading the libretto doesn't make sense unless you see it in action, because you can say words and portray something else at the same time, and they're two different things. [The protestors] think they know the opera because they've read the libretto. I would say, first of all: Please see the production, and only then can we talk, about anything. This opera does not choose sides. This opera does not promote terrorism. It's not a Jew-hating opera; it's nothing that they're claiming it to be. I said it in rehearsals: "How are these people saying all these things about this opera, and I'm watching this beautiful masterpiece unfold in front of my eyes, when I'm sitting in the Met auditorium." I don't know what to do to give them peace. Just come and watch it, and be open.

When the opera was staged in St. Louis in 2011,public conversations took place with the community. Why has the Met accepted to back down on some programs, namely canceling the live theater transmission of the show and the discussion panels that were planned ahead of the premiere?

This opera was supposed to be in movie theaters around the world live in HD, and [the Met] took it out last June, which was very upsetting for a lot of us in the cast. I know a lot of people around the world that can't make it to New York, and they're saying "What a shame." It's been taken away from everybody else who could have possibly have the opportunity to see the show, and probably heal all of the accusations about the show since its inception.

Though it's a difficult piece to watch for anybody, in the end, Mrs. Klinghoffer, the widow of Leon Klinghoffer, gets the last word in a stirring aria...

That aria just rips your heart to pieces. It gives me chills and makes me want to break down into a corner and cry for her.

Is the opera, then, meant as a way to carry on the memory of Klinghoffer through this tragedy?

It's part of human nature to carry on and move on. Klinghoffer is not redeeming for the terrorists, but it's redeeming for any culture that's been oppressed, or suppressed. When you say it's tough for people to watch it, I was thinking about the first time I tried to watch 12 Years a Slave. I couldn't make it through half of it. I had to leave the movie theater. It took me at least a month to go back, and force myself to watch the entire thing. I was getting weird thoughts on racism and slavery, and walked in with all these negative thoughts. Once I watched it, from the beginning to the end, it completely changed my mind about the movie itself. It's showing slavery in such a brutal way. I thought at the very end, Well, this is what happened, and this is how you do tell the story to actually show everybody what really happened. It's not sugarcoated. It hurts to see it, but it was real.

This also really happened. [The opera] needs to be seen. Most people don't like to be confronted with things, anything, and most people don't understand it. I think this is what John Adams and Alice Goodman were trying to do: to present a side that hasn't yet been presented. Yes, in the opera, the Palestinians sing more than anybody else, and yes we learn more about their history, but we already know the history of Israel. Everybody needs to be heard.

The Death of Klinghoffer opens on October 20 at the Metropolitan Opera, in New York. For more information and tickets, go to

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays