In the ring with the velveteers, the heavy hitters of New York’s first all-gay boxing class.

July 08 2014 2:40 PM EST

May 26 2023 1:34 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

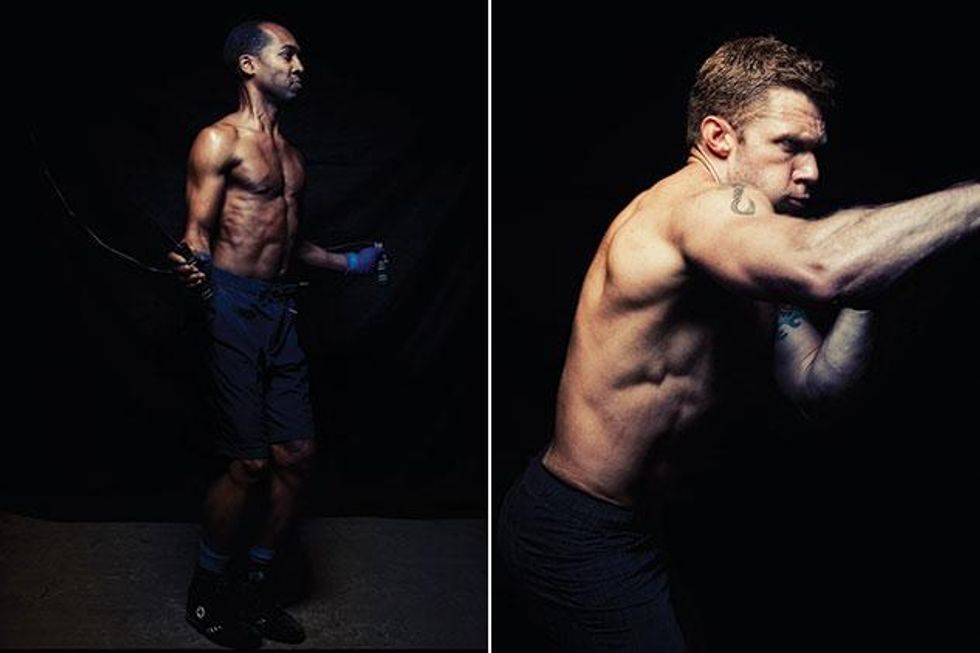

Photography by M. Sharkey. Shot on location at Gleason's Gym, Brooklyn, N.Y.

"I always emulated my father," says Myles Valentine, pulling his shirt down after showing off the 15 stab wounds etched into his ribcage, back, sternum, and face.

We are having coffee on a drizzly afternoon in downtown Brooklyn. Now 57, Valentine spent much of his early life upriver, doing 21 years of hard time bouncing around New York state's most notorious maximum security prisons: Clinton, Comstock, Elmira, Auburn, Downstate, Green Haven. He did four straight years in 23-hour lockup at Southport. During that time, learning to box gave purpose to his days.

SLIDESHOW | MEET THE VELVET GLOVES

"In prison, all the best boxers were what we called 'booty bangers,' " Valentine says, a term for inmates who expect sex in return for small acts of kindness, like a boxing lesson or a cookie left on a bed. Valentine wasn't a banger -- he wants to be clear about that. In fact, he says he was sent to solitary confinement for attacking his first trainer in lockup, a guy called Louie Comstock -- named after the prison -- when Comstock made a pass at him.

"In prison you have two sides, predator and prey, and the thin line between that is the religious converts," Valentine says. "I was a predator, but I was a nice guy."

One morning in 1972, at the age of 15, Valentine ran away from his Flatbush, Brooklyn, home, and began sleeping on the subway and living off candy bars. His father was a violent disciplinarian and Valentine had been fighting kids in school -- many of whom teased him for being a Jehovah's Witness -- since the first grade.

Around the same time, teenage boys in north-central Brooklyn had popularized street fighting. A slapdash, knuckle-brawling league brought delegates from every neighborhood: Fort Greene, Bed-Stuy, the Marcy projects, Farragut, East New York, Bushwick. They sent their five or six best fighters to weekly skirmishes in a park, guys who arrived in their best duds -- velour track suits and Kangols -- and sparred in leather gloves using a street technique known as the 52, a style involving hand blocks that's been passed down through generations.

But formal training in prison taught Valentine boxing's most important axiom. "This game is about being a gentleman," says Valentine, a trim man of about 5-foot-9 with a solid gold grill. "When you know you have these tools, you need to have common courtesy. Be versatile. Always leave the door open, because you never know who will walk in."

Today he coaches. By virtue of one of his star pupils, Francisco Liuzzi, he is the unwitting man behind the curtain of New York's first all-gay boxing class, Velvet Gloves Gentleman's Boxing, a bimonthly Saturday morning class at the health club Clay, a boutique pamper palace near Manhattan's Union Square.

Today's tiny pack of openly gay professional athletes includes one boxer, Orlando Cruz, a recent contender for a featherweight world championship who married his husband last year in Central Park. Although boxing has long attracted eccentrics, dandies, and romantics, the sport remains elusive for gay men.

The Gay Games, the international summer sporting event that draws nearly 10,000 athletes to compete in 36 events every four years, included competitive boxing only once, in its inaugural event in 1982. There are no plans to incorporate the sport into the Games this year, or in 2018.

Vance Garrett, a 34-year-old event producer who lives in Chelsea, founded Velvet Gloves in November after a discussion with Liuzzi, who is Garrett's trainer at another gym. Most

sessions have sold out.

"I think there's a sense of wonder about boxing. I know, coming from a theater and nightlife background, that creating a space where people can experience a sense of wonder safely is what it's all about," Garrett explains. "I know a lot of those guys wouldn't go to a traditional boxing gym."

Blake Fortson, a 28-year-old with a genteel Georgia drawl who lives in Bed-Stuy, works as a landscape architect. He and his boyfriend, Justin, are regulars at Velvet Gloves.

"I would never train with Myles -- I'd be terrified," he says. "I love that I'm being forced to be with gay men, which I wouldn't normally do. I feel like it's so hard to just be friends with gay men."

Christopher Davis, 49, a retired Broadway dancer and current producer for the Broadway Cares program Dancers Responding to AIDS, has been a Velveteer since Day 1. "We're all concentrating so much on learning the technique, and just trying to keep up or not pass out," he says.

This being New York, the class swarms with dancers. They've found that they transition to the sport easily.

"It's like cracking a whip," says Garrett, who trained in ballet and acrobatics. "If you know how to initiate from the center of your body, your limbs will follow. Awareness of that is what sets up a great pirouette and a punch. Also, everything is in plie. If you get too pulled up, you're off your center and you're really vulnerable."

On a recent sold-out Saturday, the boxers assembled in three rows for a rigorous 30-minute conditioning warm-up before pairing off to spar with gloves and punch pads. There is no actual hitting in the club, especially in the face. Garrett assures prospective students of this when he promotes the class on social media. There is, however, plenty of sweat, leather pounding leather, and audible grunts. Instruction focuses on technique and the extreme level of concentration and coordination required in boxing, running through combos of jabs, straight punches, and uppercuts. Remaining light on one's feet is key.

New York's endless cadre of competitive gay sports organizations includes volleyball, sailing, bowling, basketball, hockey, wrestling, and rugby, but boxing falls short of fully making the leap. One of the country's most infamous boxing gyms sits just across the East River: Gleason's, in Dumbo, Brooklyn, where Valentine and Liuzzi often train. It is a place untouched by time, hosed with glory -- a shelter for wayward men, introverts, tender hooligans, and the eccentric coaches who scream at them to become fighters.

"You can look at someone and know if they are really in the game," says Liuzzi, a statuesque, eagle-eyed 36-year-old who will compete in the Golden Gloves this year.

"You have marks on you -- not just marks on your face, but on your demeanor. Doing time is part of the demeanor, too. You have a form that is built from the utility of the sport, being quick and limber. Things like big chests and big shoulders and big

biceps don't mean you punch any harder than skinny guys."

Or, as the late notable pro boxing referee Wayne Kelly put it: "Boxers, like prostitutes, are in the business of ruining their bodies for the pleasure of strangers."

"Teaching gay guys is really no different than teaching straight guys, except the gay guys tend to show up in better physical condition," Liuzzi says.

Well before LGBT athletes were media darlings, one of the most famous openly gay pros was a champion boxer and Hall of Fame inductee. Emile Griffith's death last summer at 75 made few ripples outside the boxing world, where Griffith had close ties to the likes of George Foreman, Mike Tyson, and Joe Frazier.

"Emile was way ahead of his time. For anyone to not think he was gay is absurd," says Williamson Henderson, Griffith's boyfriend throughout the 1970s. "He was a founding member of the Stonewall Veterans Association."

Books, films, and press about Griffith continue to dance around the issue of his sexual orientation. He and Henderson met at the Stonewall Inn in the 1960s and together participated in the uprising at the bar on June 28, 1969, the event that started the modern gay rights movement. Today, Henderson is the director of the SVA, of which Griffith was vice president for many years. He marched with the SVA in New York City's Gay Pride parade in 2007.

Griffith remains a legend in boxing for a fight at Madison Square Garden in 1962. That night he unleashed a string of fatal blows on his opponent, Benny Paret, who taunted him with a gay slur during the weigh-in.

"His whole family knew he was gay," Henderson says. "He wasn't secretive about it. He went out to the gay clubs more than I ever did."

After Griffith's death, New York Times columnist Bob Herbert recalled an interview with Griffith in 2005 in which the fighter finally came out. "He told me he had struggled his entire life with his sexuality, and agonized over what he could say about it. He said he knew it was impossible in the early 1960s for an athlete in an ultramacho sport like boxing to say, 'Oh, yeah, I'm gay.' "

Griffith would never see the extraordinary amount of money now flowing to gay athletes. This year, Jason Collins's Brooklyn Nets jersey was the top-selling jersey in the NBA after he was signed to the team, and Michael Sam (see page 62) won a starring role in a Visa ad before he made the NFL draft. Griffith died in a tiny studio apartment on Long Island where he lived with Luis Rodrigo Griffith, identified in the press as his "roommate," "caretaker," "adopted son," or "companion of

35 years."

Few of the Velvet pugilists had heard of Griffith. Fewer still have much interest in boxing outside the twice-monthly class. "As gay men, are we doing this class in a sense to prove to our younger selves, and to heterosexual male members of our family, that we can be gay and still be perceived as masculine men in a heterosexist

society?" Davis asks.

He recalls a class in which Liuzzi advised the students, while they were learning to uppercut, to think of someone who had pissed them off. "We just all went there," Davis says. "It's physical and emotional. It's cathartic."

During class, Davis's mind might revert back to the playground, high school, or even college, where he was a competitive cheerleader.

"I'm thinking fuck you to all those people who never thought I was as strong as they were," he says.