Cleopatra Kambugu refuses to be a victim. She refuses to be silenced, or made afraid. She simply wants to be free to live her life and love her man. It's a universal feeling, this wanting, needing to be free, but in a place like Uganda, and for a woman like Cleo, freedom is hard fought.

As one of the few openly trans women in Uganda, and in all of Africa, Cleo faces any number of challenges to freedom, but she's luckier than most. She was able to travel to Thailand for her gender confirmation surgery, though her native Uganda does not recognize her as female. That comes with its own set of problems, particularly when traveling, or trying to secure healthcare.

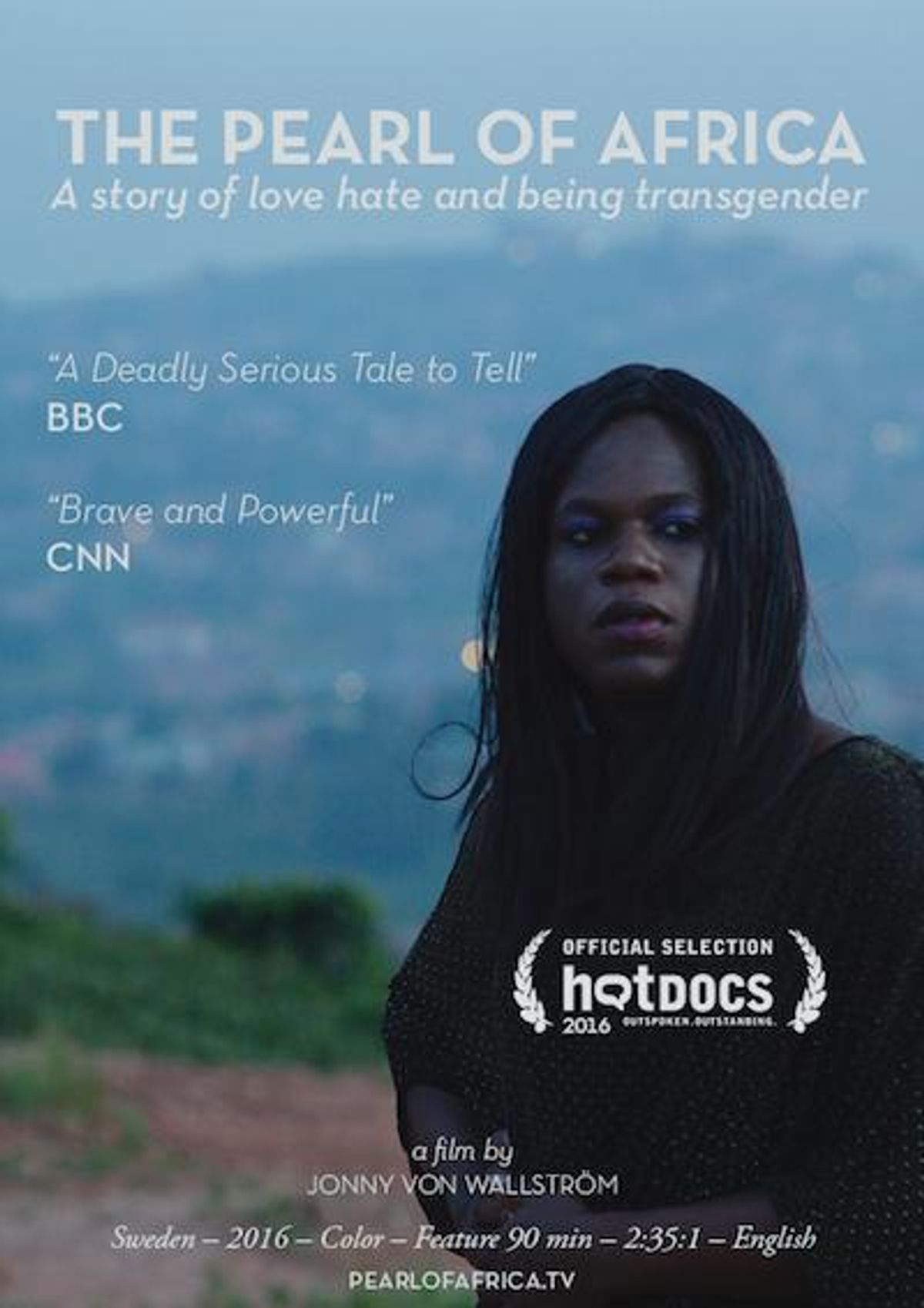

Hoping to shed light on a nearly invisible population within a country shrouded in homophobic myths and realities, Cleo began sharing her story in the popular webseriesThe Pearl of Africa. Now a documentary, Cleo's story has the ability to reach an even wider audience.

"Many films about transgender people, or black people, often focus on them being different," said director Jonny Von Wallstrom. "I wanted to fill that space with a personal love story, where the human being is at the center."

The Pearl of Africa is a love story between Cleo and her quiet, but fiercely loyal partner Nelson, who stands by her side throughout her entire journey. Wallstrom followed Cleo and Nelson for 18 months amid mounting anti-gay discrimination as she worked towards improving the welfare of Uganda's LGBT community.

Cleo was outed three years ago on the cover of Red Pepper, the nation's biggest tabloid, a week after the Anti-Homosexuality Act was passed. Though the law was later ruled invalid by the Constitutional Court of Uganda, it made the world stand up and take notice to the dangers faced there by LGBT people. Of course, the world has a short attention span, and any number of atrocities taking place at one time, but Cleo is here to remind you that the fight is not over.

OUT: Tell me about your background and when you started to come to terms with your gender identity.

Cleopatra Kambugu: I grew up in a family of 12. I come from a family of 12 children. I was one of the last four born who lived with my dad. My dad raised us as people who are able to express themselves without fear and with agency and that's who I am. That's how I'm able to express myself when I'm called to it.

I didn't have so much information. Even now, I'm uncomfortable about the label transgender, but that's what I'm called right now. I started questioning my gender identity when I was in university, combing the internet and books in the library about gender, [about] whenever people identified outside the binary in different cultures [like] in India--and this is even before I got to LGBT. I started looking up trans-identifying individuals on the internet. There were people who shared information about how they were dealing with it mentally and medically. I would say it was about that time that I found comfort, but I didn't quite have a support system. I was 23 or 24 when I started to discover the LGBT community in Uganda and interacting with them.

What's the atmosphere in Uganda like for LGBT people?

It's quite hard. For most people, it's about really being on the down low and being a bit anonymous just to survive. Coming out means a lot of things. It means having to deal with how people will [react and] the backlash that will come with [it]. How I present, and transgender people present, how they express their gender is looked at as atypical and wrong. It's better to hide it. For me and for other transgender people, you don't really decide to come out.

I've found trans people who have been able somehow to access medication but [if] you don't have the legal papers that speak to your gender your papers and travel documents are generally obsolete because you can't use them. Even if you could use them, when people find out that you're transgender--[from] whatever is in your document that your government won't allow you to change--it's difficult to access a job. It's difficult to travel. It's difficult to access any health insurance. You can access healthcare through a private hospital, which is quite expensive, and given all the different layers of not being able to have medication, not being able to have employment, and not having an income, it's very difficult to access private healthcare. It's quite bad.

Is there a strong activist presence there?

Yes, there is a very strong activist presence. I was working with an organization called Trans Support Community in Uganda up until that time I was outed through a local tabloid. I currently work with an organization called UHAI EASHRI (The East African Sexual Health and Rights Initiative), which is a division of activists that works to resource LGBTI and organize events in Africa. That's where I work currently as a grants administrator.

You mention in The Pearl of Africa that it's less difficult to be trans than gay. Do you still think that?

While we might have a judicial system that seems to be progressive, and while we might have voted down the anti-homosexual act, a lot of work needs to be done in shaping perceptions, shaping attitudes, and conversations around sexuality and gender. It's just part of the very many sexuality and gender issues that Africa has been grappling with. [Queer people have a lot of input] in terms of shaping these conversations and helping people understand and appreciate the plight of LGBTI people and that their plight is no different from that of any other African or Ugandan person here.

Do you fear for your safety?

I do. I do fear for my safety and my life. When I'm traveling, I'm often asked if the documents I'm carrying are actually mine or from some other person. In some instances, I've had to have a medical examination to prove that those documents are my documents and it's very undignified to have to go through. But I also know that the plight of transgender people who haven't even had surgery is even worse than mine. They don't have the privilege that I had to have been able to have the surgery. I really think about how undignified it would feel to have to strip naked at border points in East Africa, to prove they are of the gender that they are expressing. So many other trans people can't access healthcare, in terms of hormones, so they--and I don't like to use this term--but they don't even pass and what it means for trans people who can't pass is that their plight is harder. That's harder on them because they can't speak to the gender binary.

Do you think things are changing?

I would say things are changing because there are so many activists who are trying to do this change. A colleague of mine once told me that, "Even if people are talking about something, then change is coming." People have started a conversation around gender and sexuality in Africa.

What's the biggest challenge toward change?

If I was to point to one thing it would be general support. We need a lot of support in whichever form that comes. For people to come on board and see something's wrong and do something about it. When people come together to make change happen, then change starts happening even faster. A few courageous LGBTI activists have been able to start this conversation, however they seek for the whole world to address the plight of LGBTI people. It's an issue that still needs to be moralized. I feel like the world needs to remember the very many other superficial identifiers that have been used to discriminate against people and what that has made. This shouldn't be another conversation about superficial identifiers leading to people being discriminated again. In different countries it's religion and in Africa right now, it's sexuality and gender--for someone to be denied access to social amenities and to justice just because of who they sleep with or who they identify as. It is wrong and I feel that's a conversation that needs to be pushed.

Have you seen trans representation in the media, and if so, what's your general opinion of it?

Yes, I have, mostly from America. I like that the media informs the public that there is this other variable of humanity, this other variable of gender that's called transgender people. Just enlightening them about gender beyond the binary. What I don't like about what's happening right now, is that people that are transgender are trivialized. I don't like how trans people are portrayed in certain documentaries and movies and I would like to see trans people lead the narrative about trans people. You don't have a trans person being played by a man, [but] trans people actively participating in telling these stories about their realities and just informing the world about who they are.

Was it tough to tell your story on camera? Did you have reservations?

Jonny [von Wallstrom] basically followed me around anywhere. He wanted to shot good and bad moments. Moments where I was struggling with getting back on my feet after my surgery. That had to be shot in order to know what it means to have surgery. To experience and live through my journey. It's a story about hope. It's a story about how it can be done in Africa. It can be done anywhere else. It's a story for hope for trans sisters and brothers here. I felt like someone had to start speaking.

How did you and Nelson meet?

Nelson and I met in 2004. We went to the same high school. We were in the same class. We used to use the same men's room. For a long time, we weren't completely out as a couple because at that time I hadn't started transitioning. He's what society called a heterosexual man [but] what that meant for him was having feelings for people who are transgender. Society wonders why he makes that choice, what that is a reaction to. He was battling that. "I'm a straight man, why am I interested in someone who [is trans]" and what that means. We started and it became easier when I started transitioning and I was able to "pass" as a woman. That made it easier for us to express ourselves in public, but also, through the whole journey [raised questions about] what it means to be in love with a transgender person and how to deal with the whole backlash from your family, friends, colleagues, your boys when they look at you. He's an introvert.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about Uganda and Africa?

There are so many misconceptions about Africa, but for me, one of the biggest misconceptions about Africa is about victimhood. I don't think we are [victims], I don't like how we are portrayed as a continent that is shrouded in victimhood.

Would you ever want to leave Uganda?

No. I don't want to leave. I'm staying in Kenya right now, but I'm able to interact with my community in Uganda. It's a good place for me because I can still go back home and work. To continue that fight around realizing social justice, liberty, and equality for people who are LGBTI. I'm one of those people who wants to stay and fight. I called this fight. I need to do that for myself.

What's your biggest dream?

To be able to live in a world that's not judgmental. That can think and respect differences. You don't have to understand something to respect it. You don't need to label something to understand it. You don't have to put logic to everything you see, sometimes experiencing humanity and life is just breathing in and breathing out and just experiencing it.

The Pearl of Africa premieres April 30 of the International Spectrum program at the 2016 Hot Docs Canadian International Film Festival.