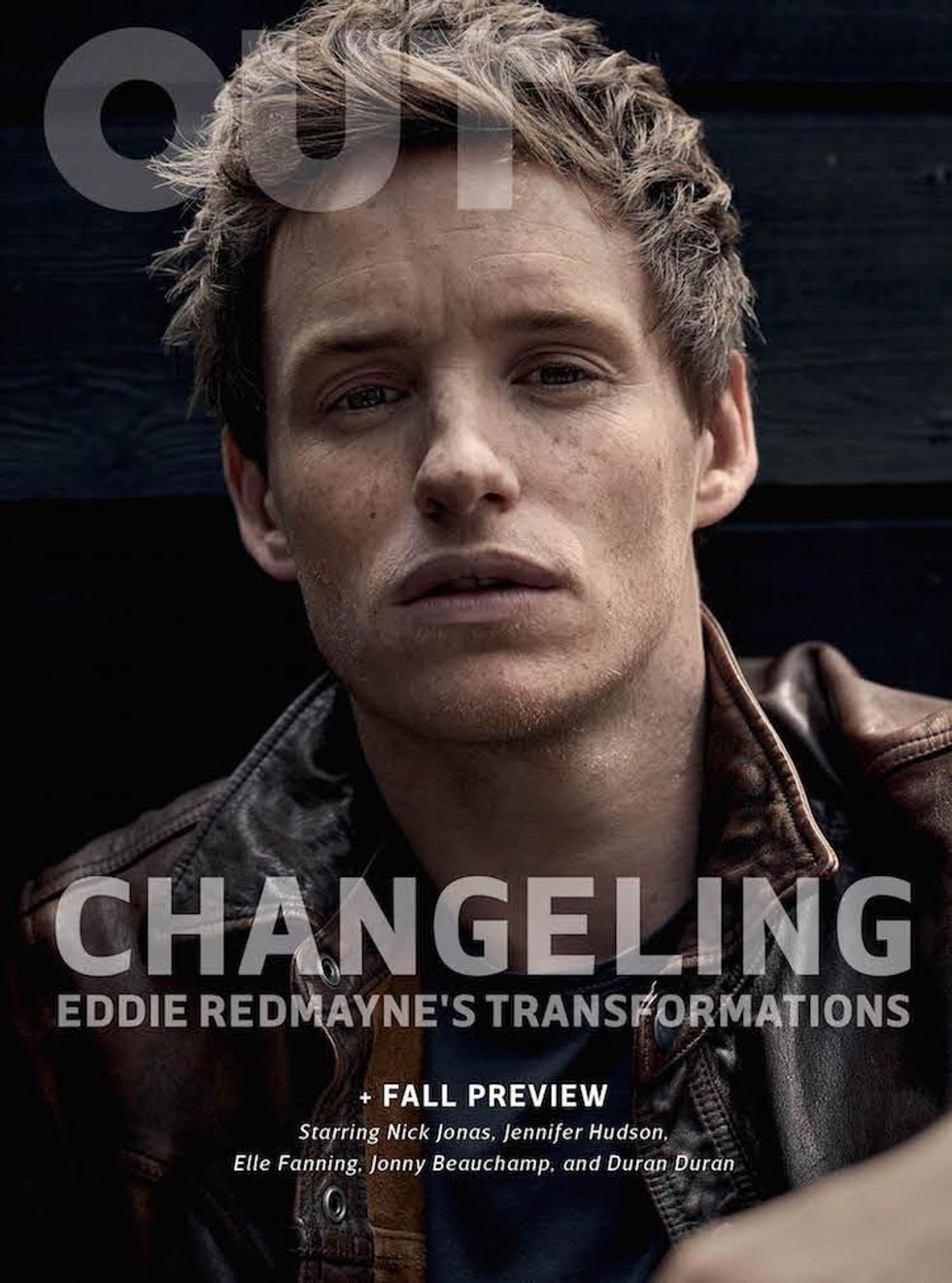

Photography by John Balsom | Styling by Grant Woolhead

Eddie Redmayne had a rude awakening on LGBT issues in 2008, when he was rehearsing Now or Later at the Royal Court Theatre in London. He was playing the gay son of a fictitious American president. "His father was negotiating with Iran," he says, sitting in a subsidized arts cafe in South London. There was a line Redmayne was not quite delivering, one that centered on the significance of the negotiations for his character. The director, Dominic Cooke, had to explain it. "Dominic said, 'Ed, you know, it's not just a line. I'm not telling you to do this, but you can find images [online].' " The actor, a firm believer in the power of incorporating every iota of knowledge he can find into a role's gestation, took a look when he returned home that evening. "It's so fucking shocking, people hanging for being gay."

Redmayne opened 2015 leaping from the red carpet to his winner's speech to an after-party in an awards season that gifted him the big four: Best Actor at the Screen Actor's Guild, Golden Globes, BAFTAs, and Academy Awards for his portrayal of Stephen Hawking in The Theory of Everything. The performance drew comparison with Daniel Day-Lewis's in My Left Foot, though Redmayne's great triumph and skill were to find the lightness and attractiveness of Hawking's disability, the exact inverse of Day-Lewis's visceral reading of physical incapacity.

He keeps his Oscar statuette on a side table and still sometimes stops in his tracks when he gets home drunk to find it sitting there. "I'll come back and sit on the sofa and -- argh!" He mimes jumping out of his skin. "You check that it feels real." He isn't quite sure how to go about getting it insured. "I haven't yet. I probably shouldn't say that, right? But I don't know what its value is. You can't sell them -- you're not allowed to. So when you call the insurance people, what do you say it's worth?"

There were psychological processes to go through, too, juggling the promotion of one pivotal role with the production of another. By the time of the Academy Awards, he had begun filming another part: playing 20th-century transgender icon Lili Elbe in The Danish Girl. "I can't tell you how nervous I am at the start of a thing," he says. For the two weeks before winning his Oscar, Redmayne had been shipped from a drab West London supermarket car park meeting point to a stage set to film possibly his most challenging role to date.

Anxiety has been a recurrent problem for him at work, something he attributes to never having attended drama school. When he was filming 2007's Savage Grace with Julianne Moore, the first project that drew wide public attention to Redmayne, he was in thrall to the actress's ability to switch from casual conversation into character at a glance. "She has this extraordinary capability. Everything about filmmaking is nerve-wracking. You're supposed to be at your best when you're most relaxed, and yet everything about being on set is unrelaxing."

The high-octane publicity circus for The Theory of Everything didn't help. "People are just asking relentlessly: 'How does it feel?' And you are trying to come up with an answer and can't because there is a part of you that is going, I actually have no idea. I'm just trying to keep my head afloat."

A born people pleaser, Redmayne is generally able to keep that anxiety mostly invisible to the common eye. "I am a very, very lucky man," he announced in his midnight blue Alexander McQueen tuxedo at the Oscars, a sharp distillation of his public persona. At surface level, there is none more privileged. He was born and raised in the pristine affluence and luxury of Chelsea, West London, the son of wealthy parents working in property and finance. He was schooled first at Eton, Britain's most prestigious private establishment (his classmates included the heir to the throne, Prince William, and Redmayne's acting ally Tom Hiddleston), then at Cambridge University.

There is a vaguely Downton Abbey aspect tracing the four contemporaneous British film stars of his generation who have settled in most comfortably at Hollywood's top tier -- with Redmayne and Benedict Cumberbatch holding court upstairs, and Tom Hardy and Michael Fassbender grittily polishing the silverware below. The latter seem to have emerged out of the same gene pool of British working-class matinee idols that gave us Albert Finney, Terence Stamp, and Michael Caine; the former in the dandier mold of Laurence Olivier. Because of The Theory of Everything, Hawking's personal blessing of his performance in it, and an unencumbered awards haul, Redmayne is now lord of that particular manor. He wears it with the 'What, me?' humility that has marked his publicity folio so far.

Underneath his glittering career and obliging public disposition is a man of curiosity, intelligence, and sensitivity. The London mayor Boris Johnson and British prime minister David Cameron are both old Etonians. Redmayne could not be further removed from their social model of blustering, curt certainty. He has none of the command of a room possessed by those elder acting Eton alumni, Dominic West, and Damien Lewis. He is warm, effervescent, and seems unsure why life has dealt him the cards it has. When he becomes animated on a subject, he is like a puppy finding its first ball of wool, pronounced freckles dancing about his face. He says he specifically chose the cafe where we meet because of his sentimental attachment to it, and becomes progressively more enthusiastic as he recalls all the performances he prepped for in the adjoining rehearsal rooms, his voice lifting in register with each memory. He has tangible bouts of class guilt and works with a charity to enable those less privileged through drama school. He is categorically one of the good guys.

"I try to do little things to find a way to help," he says, "But really, it is just about having to accept that I have been exceptionally lucky." He liked Eton. "It really is about friendship. You live intensively with these people for five years, from the age of 13 to 18, and those friendships are pretty solid."

When you begin studying Redmayne's acting resume, gender is a recurring factor. I wonder aloud why that might be. "I don't know," he says. "But it's riveting." An early role, while he was still a Cambridge undergraduate, was playing Viola, the girl who pretends to be a boy, in a 400th-year anniversary stage production of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night. It mirrored his dramatic experiences at Eton. "Because I was at an all-boys school, I played a lot of girls' parts as a kid," he says. "I look identical to my mother. Everyone's always told me that, all my life." He doesn't remember it being an issue for his classmates. As he was wrapping production for the film version of Les Miserables in 2011, director Tom Hooper gave him the script for The Danish Girl. "I found it profoundly moving," he says.

The script, the handiwork of playwright Lucinda Coxon, was the story of Einar Wegener, the Copenhagen artist whose gender confirmation surgery in Germany in 1930 is believed to be one of the first successful examples. "I knew nothing about it, going in," he says. "It felt like it was a piece about authenticity and love and the courage it takes to be yourself."

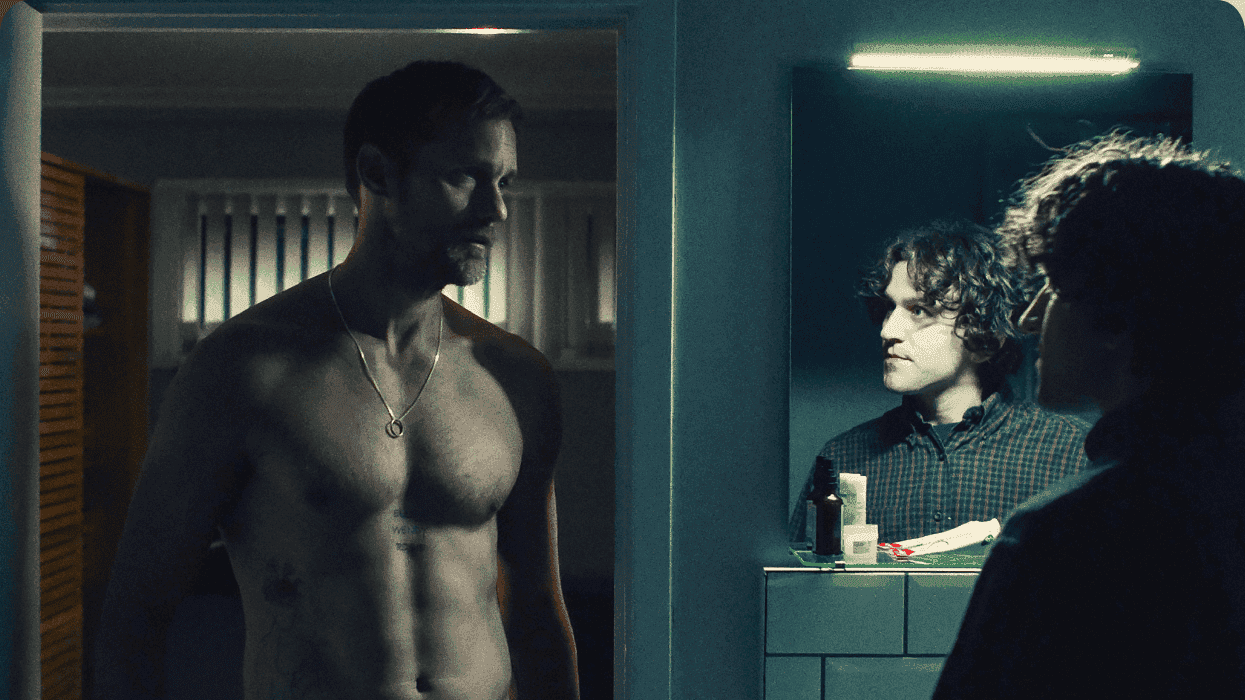

In 1904, Wegener married Gerda Gottlieb, another artist, for whom she posed as a woman, unleashing a previously untapped sense of her authentic self. The pair moved to Paris and Wegener lived as Lili Elbe, the Danish girl of the title. Redmayne's supporting cast includes the luminescent Alicia Vikander as Gerda and the formidable character actors Matthias Shoenaerts and Ben Whishaw. Hooper, the director, is a former Oscar winner himself for The King's Speech.

Between Les Miserables and The Theory of Everything, Redmayne shot Jupiter Ascending under the instruction of transgender director Lana Wachowski. "What an extraordinary woman," he says. Because The Danish Girl was by then waist-deep into development and Redmayne had begun serious self-schooling on trans issues, he spoke with her about it.

"This project had gone in and out and I didn't even think it would ever get made, if I'm being honest," he says. "But I did start talking to Lana about Lili and she told me how important the book, Man into Woman [an edited collection of Elbe's letters and journal entries], was to her. And also the art, specifically of Gerda. She very kindly continued my education, pointed me to literature, and where I should be headed." The Danish Girl is an adaptation of a book of the same name by David Ebershoff, a fictionalized account of Lili's life.

Redmayne is currently rehearsing the role of Newt Scamander in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, the Harry Potter prequel, next door to the cafe. Proving that if you look hard enough, the gender question is everywhere in the modern public discourse, he found a trans emblem in Potter world.

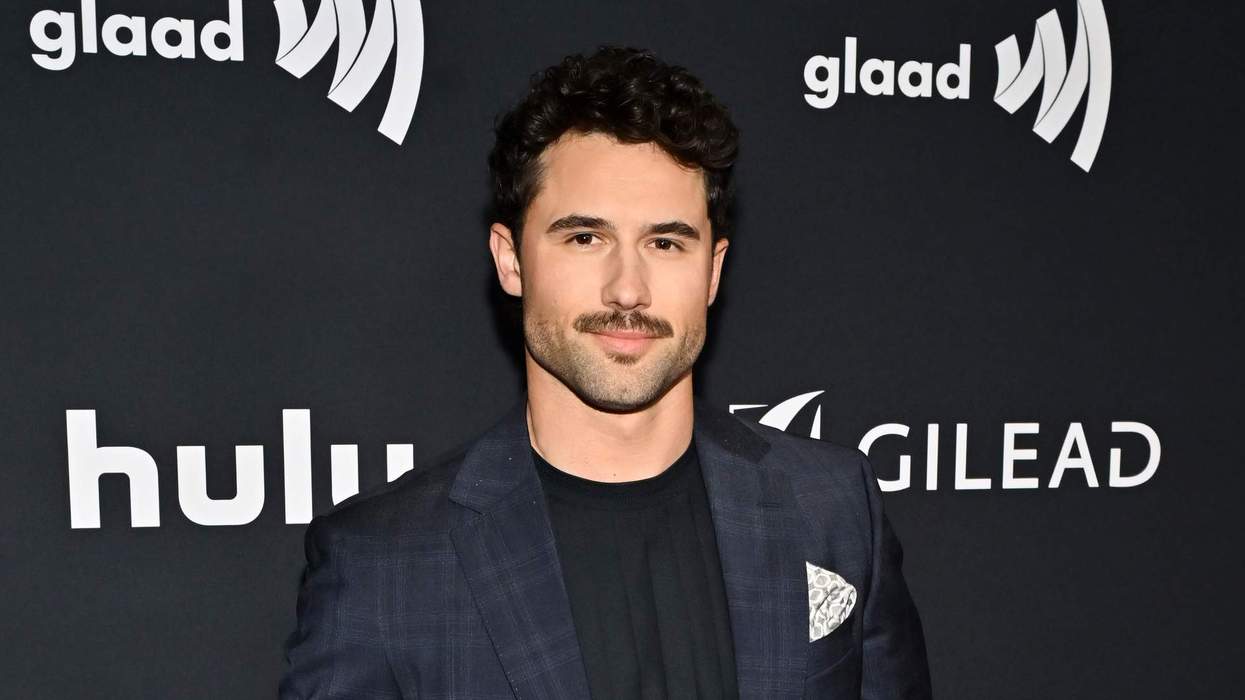

"I was watching this thing recently with this trans guy called Jackson Bird, who is huge in the Harry Potter fan community and has just come out. He does all these video blogs and is the most charismatic guy. They're normally about the Potter world and hearing him taking his audience and going, 'OK, so I've got something to tell you...' It's just extraordinary to watch. It's another generation."

Redmayne says that he does not think in a gendered way. "No, not massively." He is not sure how male he feels. "God, that's an interesting question. I don't know if I ever think of it like that." He stumbles to recall whether there were traditional male and female roles prescribed in the house in which he grew up. "I suppose it depends what you think of as masculine and feminine. I was musical, and I was into theater and arts, but I was also into sports, so I had quite a broad spectrum. I can also totally see that other people see a femininity in me." He has been aware of this perception before, in life as in work. He is not a butch man. "No. No, no, no, absolutely not."

In the three years between being cast as Lili Elbe and playing her, Redmayne's research took him far from the texts Lana Wachowski first recommended. He began with Jan Morris's Conundrum before moving on to Kate Bornstein's pivotal gender theory work. His first research meeting was with the volubly outspoken and powerful British trans activist Paris Lees. "She was the first person I'd met when the film had been green-lit," he says, "and she was very kind to me, actually. Gorgeous."

Lees took to Redmayne. "I really liked him," she says. "He's a nice, affable lad." The meeting took place at Redmayne's apartment last summer. "The grand piano didn't impress me -- it was the little details," Lees explains. "He has lovely cupboard doors. I asked him what he thought of people criticizing him for playing a trans woman. He said, 'Look, I've just played a man in his 50s with motor neuron disease. I'm acting.' I found that hard to argue with, and it really helped with my thinking on the subject."

There is a potential foreseeable problem in the trans community with the casting. "As a trans woman, I don't think that if and when they make a biopic of my life I would want a cisgender man playing me," Lees says. "Politically, it makes me groan. But if anybody's going to do this justice, then I'm happy it's Eddie. We had a good chat about everything."

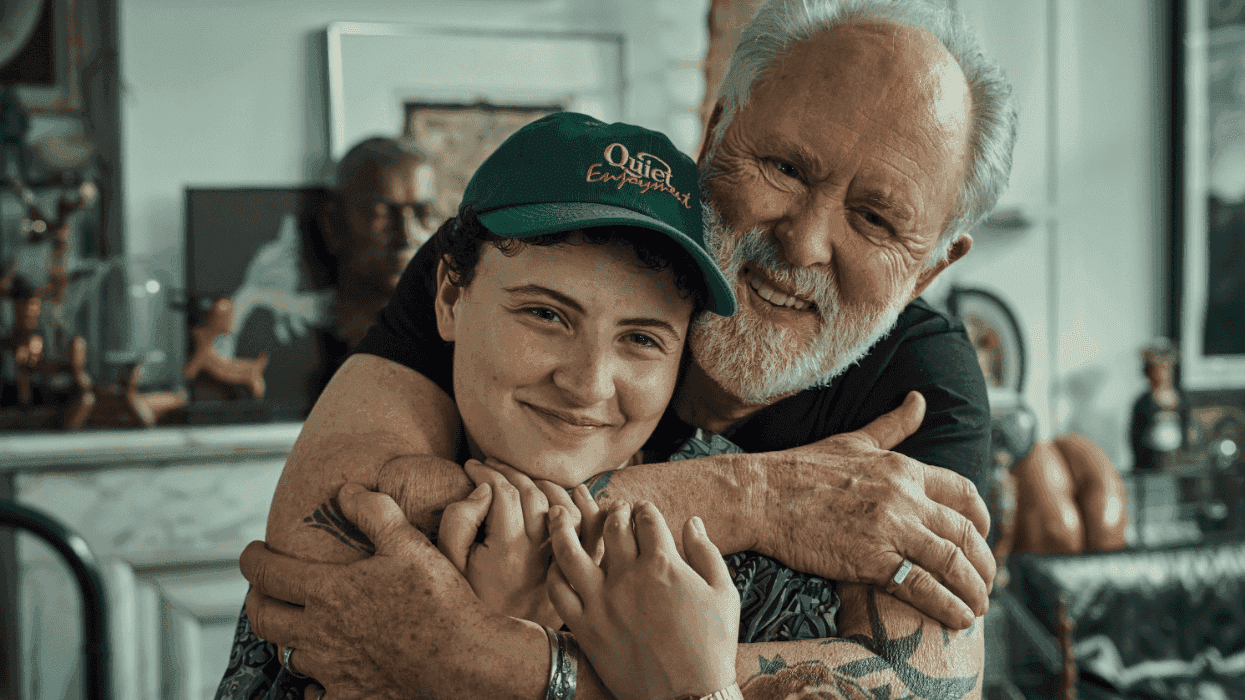

Redmayne's next port of call was April Ashley, now 80, a former Vogue model whose career took a tumble when her birth identity was uncovered in a newspaper article in 1961. "Eddie and Tom Hooper came to me for advice," says Ashley. The three of them went for lunch. "The first thing Eddie said to me was, 'Oh, April, before I can say anything to you, my father sends his love and tells me to say thank you for all the lovely dances you used to have together at [the '60s London nightclub] Tramp.' I was terribly amused."

But there was a serious undercurrent to these meetings. "People were so kind and generous with their experience, but also so open," says Redmayne. "Virtually all of the trans men and women I met would say, 'Ask me anything.' They know that need for cisgender people to be educated. I felt like, I'm being given this extraordinary experience of being able to play this woman, but with that comes this responsibility of not only educating myself but hopefully using that to educate [an audience]. Gosh, it's delicate. And complicated."

This is the first time he's spoken about the role of Lili Elbe, and he is palpably nervous about all that comes with it, partly because it is the first film he will promote as an Oscar-winning Best Actor and partly because of how much trans issues have skyrocketed in the public consciousness in the light of figures like Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner.

"I was in New York when the [Jenner] Vanity Fair cover came out and I was reading The New York Times, and all of the op-ed pieces that were being written about it," Redmayne recalls. "The dialogue was so rich and full, with everyone having opinions. Then I came back and saw the trailer for the film."

The focus of his three years of educating himself since first reading Coxon's script suddenly sharpened. He's kept a keen eye on Jenner's tale. "I absolutely salute her courage. Hers is a very specific story, and it's one that shouldn't stand for everybody's. But it is amazing what's she gone through and how she's done it."

Redmayne is more than aware of the importance Jenner brings to trans visibility in the mainstream. "It's a civil rights moment," he says. In response to the suggestion that the trans movement is now at the point the gay rights movement was 30 years ago, Redmayne says that it makes sense to him.

"That's legitimate. I think that's a really good point. My greatest ignorance when I started was that gender and sexuality were related. And that's one of the key things I want to hammer home to the world: You can be gay or straight, trans man or woman, and those two things are not necessarily aligned."

He hasn't seen The Danish Girl yet. But he will spend the last months of the year promoting it, becoming a new name dropped into the trans conversation. "I'm at this odd stage at the moment, where you've given a lot of your life to something that you care about -- a lot."

Playing Stephen Hawking may yet turn out to be Eddie Redmayne's dress rehearsal for the big one. Still, the thought of Paris Lees, April Ashley, and Lana Wachowski seeing The Danish Girl, makes him anxious. "I'm nervous," he says. "Don't get me wrong. I'll be totally honest about that."

So, what has playing Lili Elbe taught him most about gender?

"That it's fluid, I suppose. And also that it needn't be labeled."

He was delighted to read of another moment of trans rights gaining traction this year, with the announcement that the prefix Mx. was to join Mr. and Mrs. on official British documentation. The actor with possibly the most acute insight into the gender issue of his day cheered the move forward. How could he not? "You know," Redmayne says, "it feels like when you see human beings and you see femininities and masculinities in everyone. That should be celebrated."

Producer: Craig Shipman. Market Editor: Michael Cook. Fashion Assistant: Jessie Culley. Grooming by Petra Sellge