Article originally published in Out magazine No.223 (April 2013)

In 1971, David Bowie was having his Greta Garbo moment. On the cover of Hunky Dory, he looked a bit like her and sang a song called "Oh! You Pretty Things." That was his vibe when he came to visit Andy Warhol at the Factory, on September 14, 1971. He was with his manager, Tony DeFries. They were in town to sign with a new record company, RCA, and Bowie wanted to pay homage to Warhol. Andy had been a hit in London in '71 with his play, Pork, and Bowie had recorded a single, "Andy Warhol," and he wanted to sing the song to Andy in person.

I don't know if they had an appointment, but I remember someone saying, "There's somebody here named David Bowie to see Andy." I had been reading about Bowie and had heard The Man Who Sold the World. It had Bowie with long curly locks reclining odalisque-style in a vintage dress on the cover, and it only reached 105 on the Billboard charts. The Factory was the world's HQ for drag queens at the time, and I thought that Bowie was jumping on the bandwagon. But something was in the air; hippies were wearing feather boas, and, unbeknownst to us, the New York Dolls were rehearsing somewhere. I said that Bowie was pretty famous and that we should, of course, let him in.

David had long hair and was wearing huge Oxford bags-style trousers, a floppy hat, and Mary Janes with one red sock and one blue -- he was clearly aiming for a sort of eccentric androgynous look. I was immediately struck by his eyes, with their electric pupils. I was also struck by David's wife, Angie, who looked more boyish than David and had quite a presence, and by the contrast of Tony DeFries, who looked like a Sicilian Elvis impersonator. Not very glam.

Bowie had studied with the famed mime Lindsay Kemp and had toured with Kemp's company, so he certainly had the best mime credentials, but none of us knew quite what to make of the mime he performed for Andy. Then he sang "Andy Warhol." I don't think Andy could tell whether it was an homage or a send-up, with its rather ambiguous lyrics, but everyone was very nice and polite. I've recently seen the silent black-and-white video [of the visit]. The Factory's video technique was even worse than its film technique, and I'm curious about the conversation I can be seen having with Bowie, my hair almost as long as his. I recall David asking me where he could get a copy of the Index Book and I recall that I had no idea what that was.

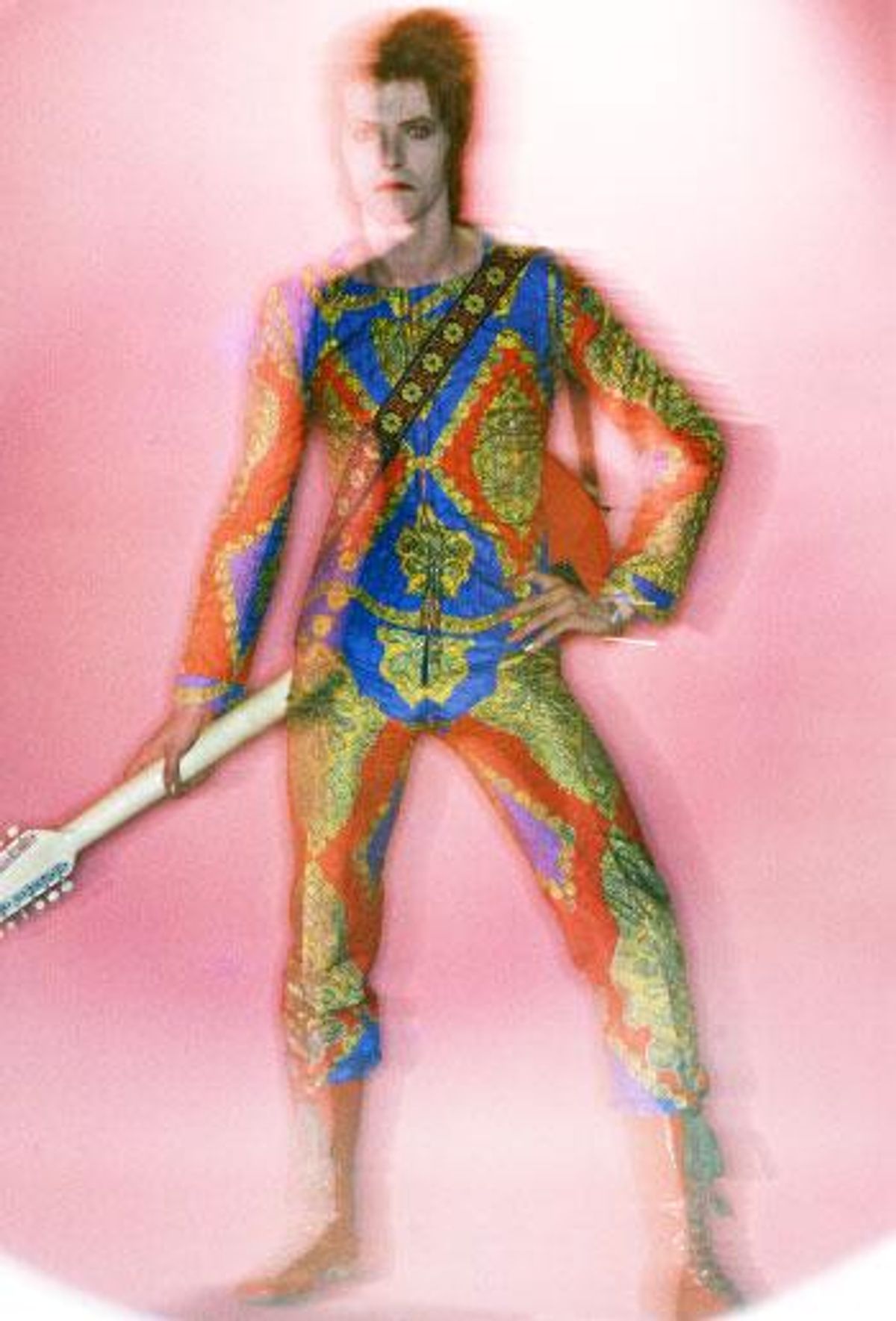

I don't know what Andy thought of that day -- probably not much, but he had that sense of judging a person's self-esteem, and I think Bowie passed on that count. The next time I saw him was in London. RCA Records had gotten behind him big time, and, in 1972, they shipped a bunch of editors and writers over to see his new incarnation, Ziggy Stardust. It was a total transformation, with Bowie gone futurist with radical red hair, makeup, and Japanese designer clothes. It was fantastic. He was a new dandy prototype, a Beau Brummell for the publicity millennium. I saw the band play a great concert in a medium-sized hall in Aylesbury, and I hung out with David and his very friendly wife, Angie. We went dancing at Yours and Mine, a hip disco under a Mexican restaurant and, yeah, I danced with David Bowie. Fabulous!

Photograph by Andrew Kent

David was not yet huge, only kind of biggish, but he was already a one-man industry. RCA had given him his own label and he had signed Iggy Pop and Lou Reed to it. On that trip I got to see both of them perform at London's Roundhouse. Lou was good, although I thought his black nail polish was a bit odd -- he still had a long way to go to Rock 'n' Roll Animal. Iggy, then silver-haired, was fantastic -- one of the great performances, in the round, on a big oriental rug he crawled his way around. I went back to see Lou, who was moving his own amps, and felt a little embarrassed to see him doing his own roadying. Meanwhile, Bowie's company moved to New York, basically hiring the cast of Warhol's Pork to run the office. They all showed up at Max's every night with expense accounts, and we wondered where the money was coming from.

But the Mainman/RCA machine was doing its job; David was booked into Carnegie Hall. I went with Andy and we had great seats. Now Andy totally got it. No more mimes or Mary Janes -- this was really the future. "Gee, it's so glamorous," Andy said. We were sitting in a cloud of pot smoke, pretty much. Andy, of course, didn't smoke, but he remarked that he didn't mind -- he liked the smell.

There was something truly fantastic about Bowie's rise. The songs got better and better -- "Jean Genie," "Rebel Rebel," "Diamond Dogs" -- but the persona was almost ahead of the music. Ziggy Stardust retired dramatically and Bowie went R&B with Young Americans, a new band, and Carlos Alomar on guitar, hitting No. 1 with "Fame," co-written by John Lennon with a riff so good James Brown stole it. Bowie just seemed smarter and smarter, more and more the silver surfer of the zeitgeist. His songs sparkled with intellect and they also hit the musical moment precisely.

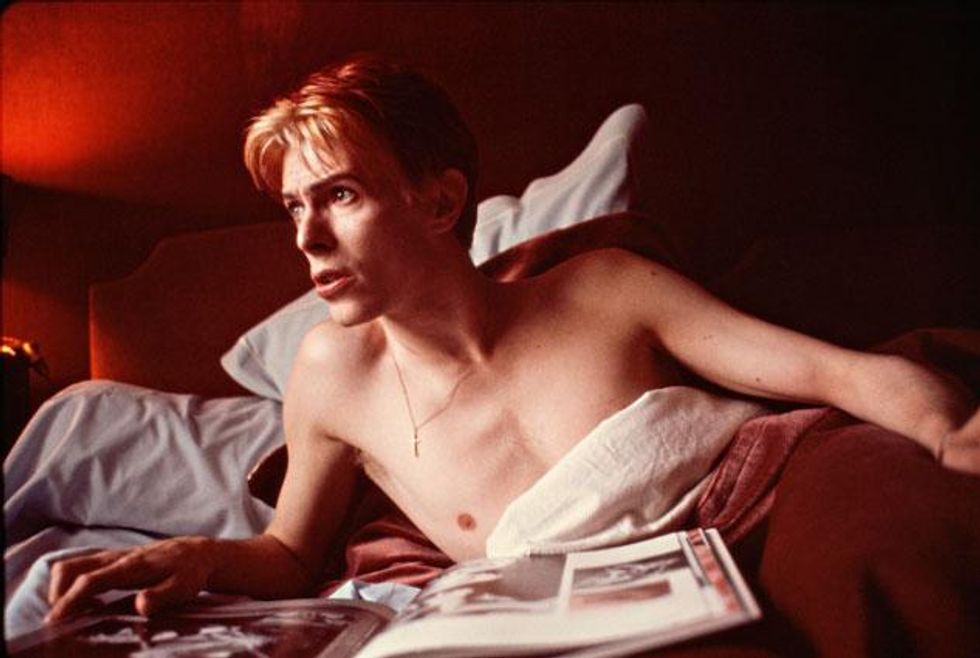

With Station to Station, he achieved total liftoff from the pop music universe into an orbit all his own. Apparently, Bowie was doing a lot of blow -- as in a lot a lot -- and living a rather unusual life in Los Angeles. Both Station to Station and Low were deeply influenced by his starring role in Nicolas Roeg's film The Man Who Fell to Earth. He had achieved a look that was really something unprecedented. He didn't look like a girl, but maybe he looked like an alien: red hair, white, white skin, and utterly fat-free. He was working in character, imagining himself as the Thin White Duke, which focuses all of his favorite mythologies and vices into a persona: cold, formal, postured, romantic, frozen but flexible, tailored, pomaded. It is said that overmedication occasionally led to odd behaviors, such as fantasizing that the Jimmy Page wing of the Crowleyites were out to get him or whatever, but it sure made for great music. He was the best, and he still is, even when he's doing nothing.

Bowie picked his birthday to relaunch himself after 10 years of radio silence. The new single, "Where Are We Now?" released on his 66th birthday, is a tender, plaintive song that seems to have had its beginning in a melody introduced in a sketch on Extras with Ricky Gervais with Bowie at the piano: "Pathetic little fat man/ No one's bloody laughing..." It was on YouTube a year ago, and someone wrote in that Bowie should release it. Well, he did, with different words, and with a rather grim video by Tony Oursler; Bowie often collaborates with art world artists, even if they make him look unbeautiful.

As I write this, we are waiting for the release of the rest of the album, which features another arty touch. It's the cover of "Heroes" with a big block of black type on white, like a cigarette warning label, that proclaims, "The Next Day." Get it? We can be heroes, just for one day. (There is also a timely Bowie retrospective at London's V&A Museum beginning March 23, for which the singer has opened his own archives.)

When it comes to Bowie, I have learned acceptance. It always turns out better than you imagined it could -- how exquisitely rare is that? Being a grandmaster is a tough job, but somebody has to do it.

Read more stories about how David Bowie influenced generations here.

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays