News & Opinion

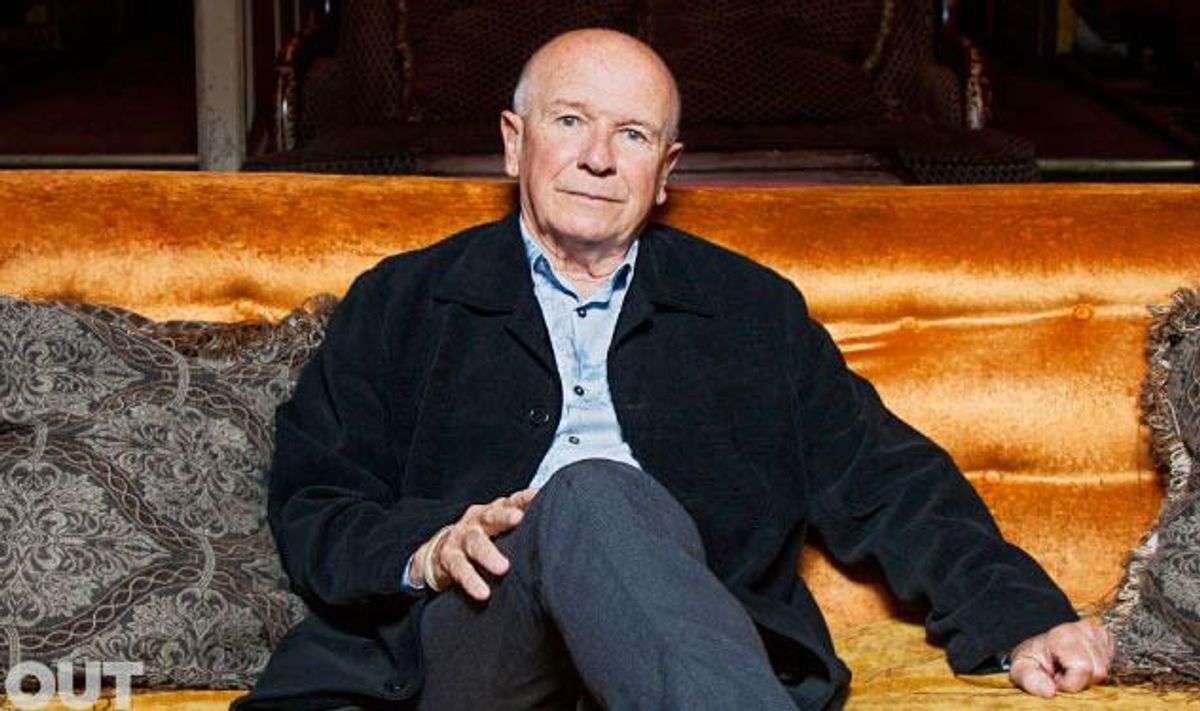

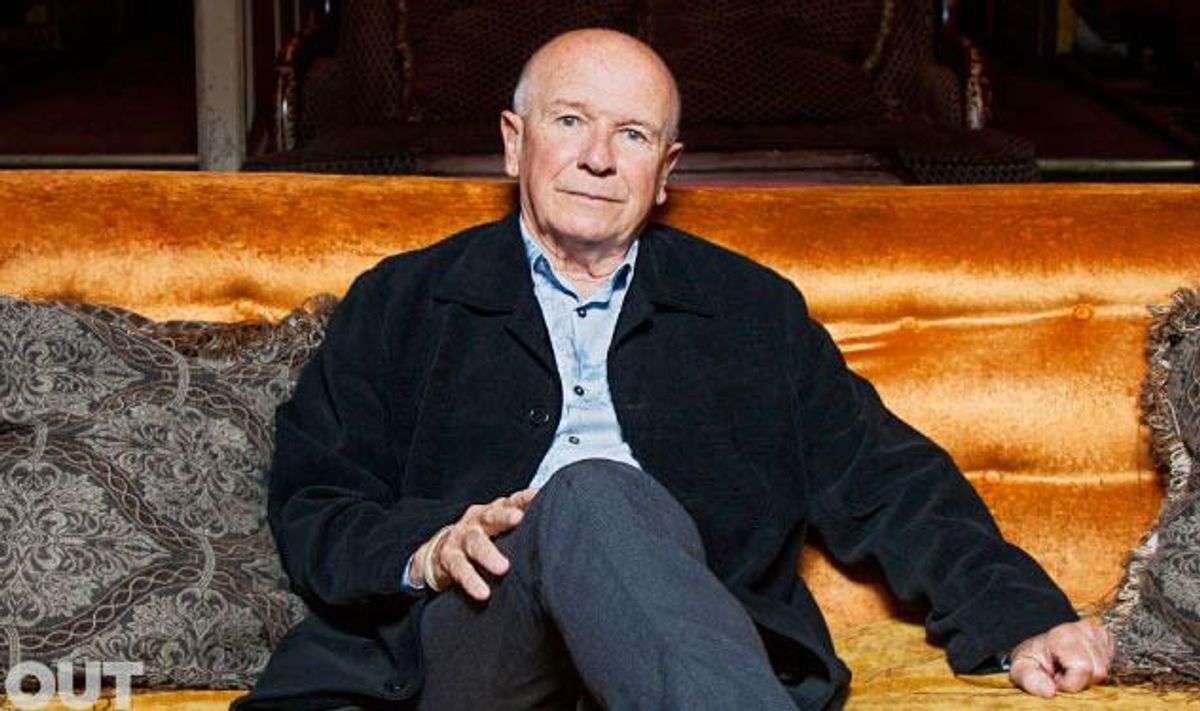

Terrence McNally’s Golden Dawn

At home with the 74-year-old playwright discussing his play 'Corpus Christi' in Greece and how 'God has a gay gene'

December 17 2012 10:08 AM EST

June 12 2018 7:51 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

At home with the 74-year-old playwright discussing his play 'Corpus Christi' in Greece and how 'God has a gay gene'

Photo by M. Sharkey for Out

Some artists never lose their boyish looks. Jonathan Franzen, John Dowd, Terrence McNally--all these men seem to retain those adolescent smiles. As Terrence McNally shakes my hand by the fireplace of his Greenwich Village apartment, his stray-dog eyes instantly accept me. I sense his reassuring look.

"My husband, Tom, is a good lawyer," Terrence says proudly, if shyly, about Tom Kirdahy, who's in the kitchen fiddling with their espresso machine. "I mean, he's the good kind of lawyer. He does pro bono work for people with HIV. I mean, he is a good lawyer, too," Terrence adds hurriedly.

"Tom is a good, good lawyer," I say. Tom turns, smiles, and asks if I want coffee. They are both excited about the panettone I brought for our get-together. It's the first weekend of December, but it feels like Christmas.

Two nights ago, I saw Terrence's new play, Golden Age, on Broadway. Naturally, I have a list of notes to bounce off one of America's most award-winning playwrights. How, for instance, does Golden Age connect to Master Class, one of his classics? But Terrence and Tom's Sunday is all booked up. They have friends in town for the premiere, and Terrence is already working on a new project, so I get straight to the point. "Let's talk about Greece and your play over there, Corpus Christi," I say, as Tom hands me a double espresso, and the three of us settle down.

In October, Greek Orthodox priests and far-right wing protestors turned violent outside Hytirio Theater in Athens, where Corpus Christi, a play that portrays Jesus and the Apostles as gay men living in Texas, was staged. Terrence and Tom have been following the uproar and are keen to hear about my latest discussion with Laertis Vasiliou, one of the play's producers and actors. "Christian Talibans" (Vasiliou's words) vandalized the theater and bullied the audience. The production froze and, to make matters worse, Bishop Seraphim of Piraeus, together with a parliament member of the far-right political party Golden Dawn, filed a lawsuit for "malicious blasphemy" and "insulting religion" against everyone involved in the play. Vasiliou calculated that they needed about 5,000 euros just for court fees, assuming they got free representation. Considering the money he put into the production that never took off, Vasiliou claimed he was broke. But, more importantly, he alleged that this lawsuit against freedom of speech and artistic expression took Greece back to the dark ages.

Tom instinctively lists a couple international organizations that may help me direct Vasiliou to alternative funding for this lawsuit.

"I was raised in Corpus Christi, Texas, as a Roman Catholic," Terrence says sympathetically. "But I never thought that I was bad for being gay. We are all sons of God. We are all divine. With Corpus Christi, I wanted to include myself in Christ's story. I wanted to see myself in the eyes of God. Why couldn't those men be gay, too? God is everywhere."

"Corpus Christi is full of love, suffering, and forgiveness. Terrence, you are obviously religious," I say.

"Well, most people who crusade against me or my work have not seen it," Terrence explains.

"Corpus Christi was playing at Hytirio theater, but it also took place just outside the theater, on the streets of Keramikos," I tell Terrence. "In a video link I'll forward to you, a young man, Panagiotis Demos, describes how on his way to enter Hytirio, he stood still and chose not to fight back, while he was pushed and punched by fanatics, including Greek Orthodox priests. Demos's stillness challenged my fight-or-run predisposition, my DNA. It is heartbreaking footage, which brings to me the actual play: 'You can come no closer to Me than your body, Simon. Everything else you will never touch. Everything important is hidden from you.' And it gets better. Vasiliou sued for blasphemy, just as the High Priest sued Joshua in Corpus Christi. Your play is being replayed on a national level. You say that that most people who fight your work have not seen it, Terrence. So how can we change that? In Greece? Today? Demos was lucky. He could have been sent to the hospital or even killed. Which makes me question when your faith, your tolerance towards the ignorant, should switch into fight for survival. How many more martyrs, how many more Harvey Milks and Matthew Shepards, and hundreds, thousands of bashed gay people around the world should be victimized before we have to admit that Jesus did die in vain? I respect you, but I don't have your faith. When do you say: enough is enough?"

"It's somewhat unfair of you to ask me these questions," Terrence replies. "My life today, my city, my work, are all so different from the circumstances you describe. I am shocked and saddened by what's going on in Greece. It's a European country whose laws still threaten freedom of speech."

"Then you have to think back," I say, almost interrupting Terrence. "Maybe Greece is about to go through its own Stonewall. Maybe we can learn a thing or two."

Terrence pauses long enough for Tom--introduced as "the politico in the family"--to come to my aid: "When Terrence wrote Things That Go Bump in the Night in 1964, he was savaged by critics for being frank," Tom tells me. "But this didn't intimidate him. He didn't stop. He pressed on. That was Terrence's fight."

"I had to be honest as an artist," Terrence tells me, though his body language addresses his husband. "Even more important than being a good artist is being honest. Not to live a secret life. That's the only way I can be an authentic person. God is in all of us. God has a gay gene, too. I'm 74, and I've been fought a lot, and I've been thanked a lot. At some point, the mayor had to step in and protect my life. He had someone walk me to the subway. We had AIDS funerals while people protested against homosexuality in the background. Then there was a mother who approached me crying on Mother's Day, of all days. She was living with the fact that she never accepted her son before he died from AIDS."

"That's a tricky one," I whisper.

"We've come such a long way since 1964," Terrence says. "AIDS, as harsh as it may sound, helped gay rights."

"But it is 2012," I say. "One should not have to go through hell to get equal rights."

"No, one should not. But I'm afraid AIDS made people come out. We don't all have to be Larry Kramer, but he made a difference. You help one person come out, you have a success. And it takes one person to start change."

"Well, that's part of the problem in Greece," I tell Terrence. "Very few people are out there. There are barely any role models."

"It's puzzling, really," Terrence says, nodding. "Greece had Kakogiannis, Diamantidou, and Melina Mercouri. During the junta, Melina lived with Jules right over there," Terrence says and points through the 12-foot-window of their living room to the building across the street. "We were in each other's place all the time. Melina was tireless. She'd work for 12 hours on Illya Darling, and then she'd go to Brooklyn to speak to Greeks about freedom. She was brave; she was full of fire."

"A remarkable woman, no doubt," I say. "Did you stay in touch with her in the 80's, when she was part of the political establishment in Greece?"

"Yes. I visited her there," Terrence replies. "We were very close."

"Melina was bigger than life. Yet, she looked the other way when the very government she was part of, supported by yellow presses like Avriani and Klik, cemented populism, homophobia, sexism and style-hunger in my country. I guess that was the '80s."

"I didn't see that when I visited her. I did not notice homophobia. Then again, I stayed in a 5-star hotel. I don't know what people said behind my back. I am sure things are different now. Socially, politically, economically. There is struggle."

"The characters in your plays are prone to suffering," I say. Terrence blushes; he and Tom laugh. "And forgiveness." I add, embarrassed, as if I were insulting a national treasure.

"Gay people have so much to contribute," Terrence says. They hug me goodbye. Their wool sweaters smell of soap . "We are neighbors. We should get together at the Italian bistro."

In their elevator, I'm smitten yet unsatisfied. Fuck forgiveness. We are at war back home. While I cross Washington Square Park, I'm all-out, with Terrence's words playing in my mind. "God is everywhere," he said. "Give the man the benefit of the doubt, you little punk! Give the man the benefit of wisdom," I mumble to myself. Summarizing the last 30 years of Greece's madness is like trying to explain Higgs's boson, the "God particle." Terrence's words surface again in my head: "We are all God. We are all divine."

How could Golden Dawn be God, Terrence? Fine. They practice separation without knowing it. They don't see "one." So, how fair was I to my country over espresso and $50 panattone? Maybe Golden Dawn is our 'AIDS,' a nightmarish trigger for action and social justice. Perhaps we needed to hit the bottom of a 30-year greed and trash plague in order to help ourselves. I take out my phone and bring up the invite for a How To Survive A Plague documentary screening. This will be good.

Read "Fear & Loathing" about the Golden Dawn party and homophobia in Greece