News & Opinion

Father Figure

How a gay man became a guardian and a mentor to a lost little girl -- my wife.

January 17 2013 10:50 AM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

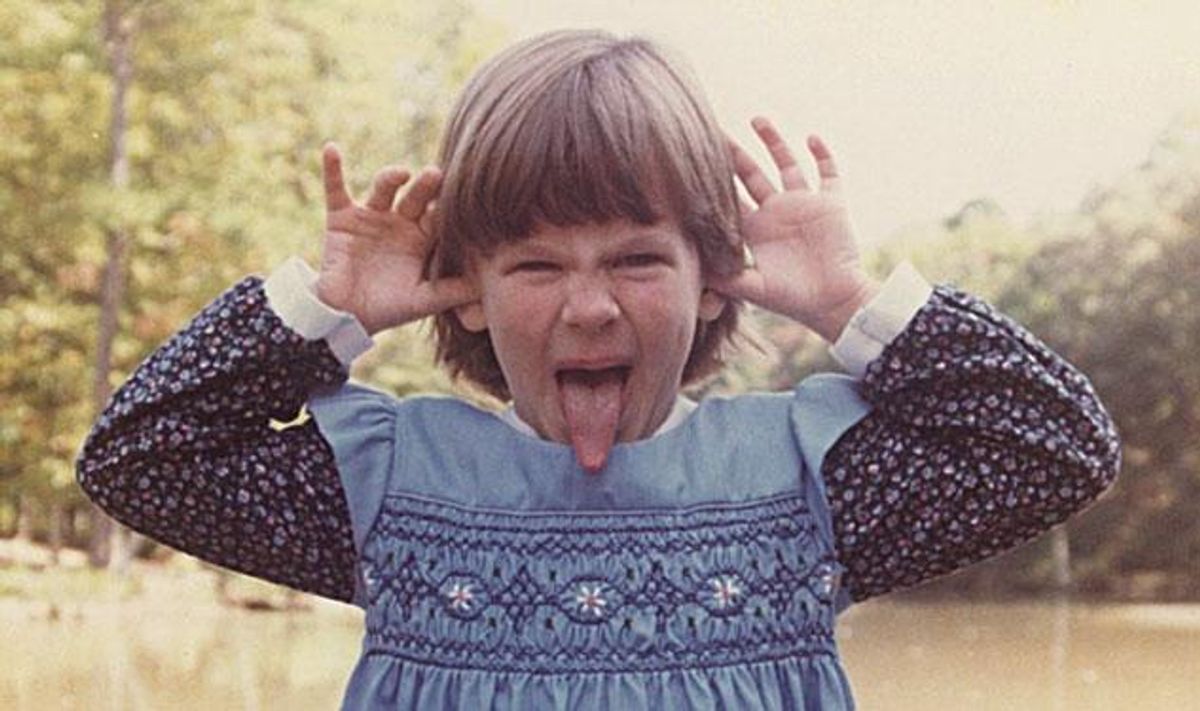

Photography courtesy Shana Naomi Krochmal

"I don't have people," my wife, Jessica, said.

We were watching Mad Men, and Don Draper was attempting yet again to escape an emotional entanglement by disappearing into a flashback. It's a convenient strategy for a fictional character -- in the real world, we have to balance the weight of family history against a functional adulthood the hard way, picking what stories to share and which to shut away.

Jessica said it like a confession, like a warning, but by our third date, I knew she hadn't seen her mother in years. Her father, a commercial fisherman, died when she was 5, his boat capsized during a nor'easter nearly identical to the one that, a decade later, was immortalized as The Perfect Storm. Her grandparents, with whom she lived in Virginia from age 11, saw her through a rebellious adolescence, but they, too, were gone well before we met.

And then there was Tommy, her mom's best friend. During those half-dozen years between her dad's death and her grandparents' intervention, he was Jessica's first line of defense, taking care of her when her mother wouldn't -- or couldn't -- rise out of the shocking, sudden grief of young widowhood, turning instead to a series of unsuitable boyfriends, alcohol, and drugs.

"Your life is like a novel," I often tell her, and as a writer, my fingers have itched to sort her childhood chaos into a simpler narrative with a beginning (tragedy), middle (struggle), and end (our own happily ever after, I hope).

I don't begrudge Jessica her need to keep her distance -- my own father and I are estranged -- but the idea that the closest thing my wife had to a stable parent during her childhood was a wildly flamboyant gay man explained, I thought, so much about the woman I loved. Tommy lived with them off and on, crashing on the couch or making himself scarce when Jessica's mom had a boyfriend. (Once, when Jessica teased a bratty classmate, the girl snapped back, "At least my mom isn't a slut who sleeps with gay men!")

Tommy braided Jessica's hair so she'd fit in with the other Catholic school girls, stayed up all night crafting an elf costume for her Christmas pageant, and, when she couldn't sleep, microwaved a mug of milk with his special ingredients: a packet of Equal and a capful of imitation vanilla. If he wasn't around, Jessica says, "My mom would just give me Kahlua."

He brought home the kinds of presents that little girls hoarded in the '80s: earrings and lace gloves from his job at the mall's novelty gift store, George Michael cassette singles, and, once, a blind miniature poodle named Missy, who of course Tommy insisted they call "Miss Thing." He'd watch Who's That Girl as many times as Jessica wanted -- after all, someone had to teach her how to apply eyeliner like Madonna.

Tommy also went out, with or without Jessica's mom, looking for whatever trouble could be found in their tiny southeast corner of Virginia. He was 6-foot-2, with blue eyes and sandy blond hair, tight jeans, and a denim jacket. (Jessica has no photos of them together; after she mentioned Tommy had done a stint in the Air Force, I decided he looked exactly like Val Kilmer in Top Gun and refused to be told otherwise.)

"Tommy liked rough trade," Jessica says. He'd drive his over-the-top gold IROC-Z Camaro down to Norfolk to pick up sailors on shore leave or cruise for strangers in alleys, and he didn't bother keeping his voice down when delivering the "I showed him mine and then he showed me his" play-by-play for Jessica's mom.

Jessica as a child at a petting zoo

On Fridays, Tommy and Jessica's mom would sometimes dress Jessica in her Catholic school uniform, but then they'd all skip school together, them dropping Jessica off at her grandparents' house so the grown-ups could have a lost weekend.

The first time Tommy walked into her grandparents' dining room, he pulled a gun out of his waistband and calmly set it on the dining table.

"Do you really have to put that there?" Jessica's grandmother asked.

"A faggot can't go out to the country without a gun," Tommy said.

"Well," grandmother replied, "you don't need it here."

When Jessica's mom took up with a younger guy Tommy didn't trust -- a 23-year-old Chippendales dancer -- he taught Jessica how to hold the gun, though not how to shoot it. "If he ever bothers you," Tommy said, "you come get me, or you come get this."

After Jessica's mom ended up in treatment, Jessica moved in with her grandparents, and even through her tumultuous, troublemaking teenage years it was still a comparatively stable, safe environment.

But for Tommy and the other fiercely defiant faggots fighting their own way through Reagan's America, there were a series of all-too-real after-school specials on the horizon.

When her grandmother called her at boarding school in the early '90s and said, "Tommy's getting sick," Jessica says, "I knew what that meant."

Home for the holidays, she visited Tommy at his mom's house, where he was sleeping on a hospital bed in the living room and surviving on a diet of "sparkling smoothies" -- rainbow sherbet, protein powder, and 7-Up -- because he had lost most of his teeth.

Just after she got back to school, her grandmother called again. "Get packed," she said. "I'm coming to pick you up for the funeral."

Despite being two 30-year-old women when we met, Jessica and I have both been living in queer culture in one way or another since we were kids. We already felt like old queens, from our comfortably camp reference points to the simmering anger and grief on behalf of the men who have died along the way.

In lieu of traditional introductions to the in-laws, we've spent years working our way through our respective social registers full of gay men who made us the queer women we are today. We have dozens of overprotective older brothers, mischievous co-conspirators, lost little lambs.

These are the men whose struggles proved we, too, could survive the worst our families and the cruel world could do to us, whose loyal friendships and lifelong love stories taught us how to take care of the lost little girls we both still carry inside.

Many of the other flamboyant father figures somehow hung on through the pre-protease sunset by the skin of their teeth. Some, like Tommy, didn't live long enough to see us find each other. But they are still our people.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right