What the hell is a fauteuil?

"Gore Vidal, Democratic candidate for Representative in the Twenty-ninth Congressional District, sprawled barefooted in a gilded fauteuil of his luxurious octagonal Empire study as he considered the question whether he would win the election."

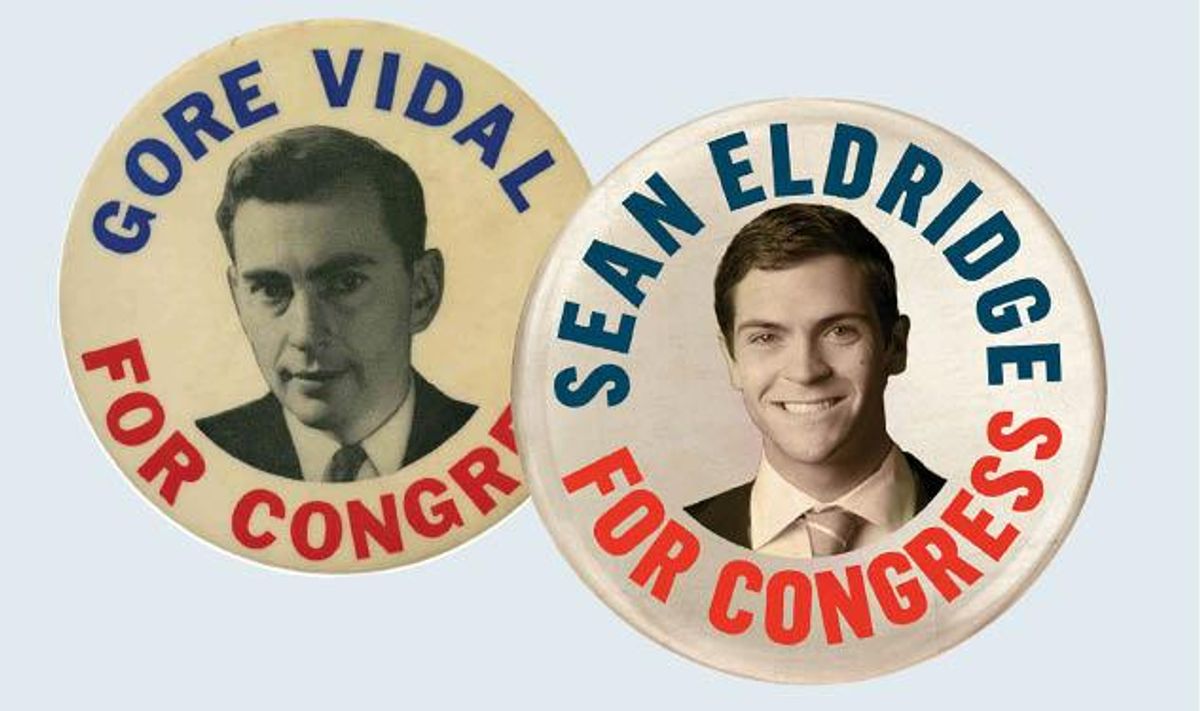

This is not overwritten fan fiction about a dead novelist. It's the opener to an article published in The New York Times in September 1960. Vidal, already a successful playwright and novelist at 34, was indeed running for Congress.

Unable to use the word gay (the Times only began allowing it in 1987), and unwilling to write homosexual, the reporter resorts to rich innuendo; readers are told that Vidal is a bachelor living in "lonely splendor in an 1820 Greek Revival mansion on the edge of the Hudson River." (Actually, Vidal's lover, Howard Austen, was living there too). The reporter watches as Vidal "lets his cocker spaniel lick the Chateau Yquem [sic] off his fingers."

"I don't drink Chateau d'Yquem," Vidal shot back, decades later, in his memoir, Palimpsest, still sore at the newspaper he believed was out to get him.

Fast-forward 53 years. Another well-connected young gay guy with an impressive house has his eye on Congress. The district lines roughly correspond to what they were when Vidal sought a seat: New York's Hudson Valley and the Catskill mountains.

His name is Sean Eldridge, he is 27, and he is married to Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes. Their joint fortune is estimated at between a half-billion and a billion dollars.

In a photo that appeared in The New York Times this summer, Eldridge wears a serious expression and his dark hair is neatly trimmed; blazer, no tie, husband beside him looking equally scrubbed in a black V-neck. What appears to be the horn of a phonograph hovers behind Hughes's shoulder, gently confirming the old saw that gays love antiquing.

There is no innuendo in the Times's coverage this time, but there are plenty of touchy questions: Will voters in a largely rural district get comfortable with a vision of squeaky-clean domesticity that just happens to be gay and fabulously wealthy? And how established in a place do you need to be in order to represent it in Congress?

Eldridge and Hughes have lived in the district for less than a year. When their $5 million mansion turned out to lie outside the district where Eldridge thought he had the best chance, they simply bought another house within the lines, for $2 million, and called it home. (They also have homes in Manhattan and D.C.)

"It's a little bit presumptuous," one of Eldridge's new neighbors tells the Times. "In a community like this, you like to know who your neighbors are. How can he expect to represent people he doesn't know?"

Like Vidal, Eldridge is challenging an incumbent with deep roots in the district.

And, sensing an opportunity, the Republicans have mobilized. They've set up a deceptive "Sean Eldridge for Congress 2014" website that includes photos of Eldridge with Nancy Pelosi, several references to Eldridge's prowess as a political fundraiser, and a generous sprinkling of words like elitist. Gay is nowhere to be found, though.

In short, Eldridge probably should worry more about being called "carpetbagger" than "queer."

For Vidal, defeat in the 1960 election became a point of pride. For years afterward, his author bio included this defiant line: "Although he lost, he ran better in the traditionally Republican stronghold than any Democrat since 1910."

Did his sexual orientation play a role?

Reporters in 1960 certainly knew Vidal had published The City and the Pillar, a coming-of-age story involving two male lovers. But pre-Stonewall, there was a cloak of invisibility around Vidal's sexual tastes. Journalists, Vidal wrote, "did not realize that their sort of gossip was almost impossible to transmit to the public in those days."

Can Eldridge, a former political director of Freedom to Marry, do better? In August, his campaign reportedly paid a focus group to watch some possible lines of attack against the incumbent. The group was also shown a dull video about high-tech manufacturing in the Hudson Valley, in which Eldridge appears, looking very much like the young president of the local chamber of commerce. He's also invested in bakeries and breweries--the kind of feel-good businesses that make good photo ops.

In 1960, Vidal didn't bother trying for any effect other than artsy, opinionated wunderkind. His play The Best Man was a hit on Broadway. He argued against war, and for more social spending, and admitted his candidacy was a long shot.

He told the Times, "If this is subversive, all right, I am out to subvert a society that bores and appalls me."

A fauteuil, by the way, is an armchair. I Googled it.