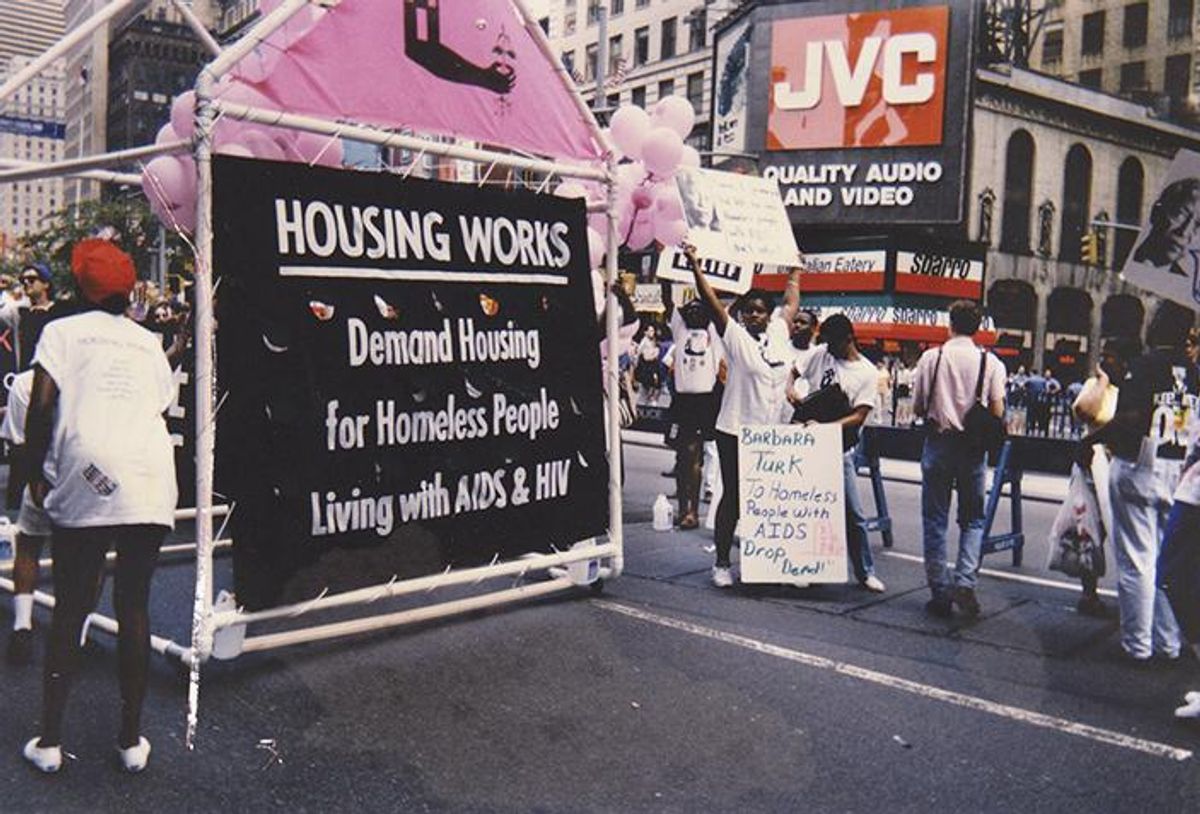

In 1997, the first wave of antiretroviral drugs was just beginning to have an impact, as the number of those dying of AIDS-related illnesses began to drop. That same year, a six-story building of 36 studio apartments for HIV-positive men and women was officially opened in New York's lower east side.

"It's taken seven years of battle waged against every level of government to see this project through," Keith Cylar told The New York Times at the time. A dogged activist and co-founder of Housing Works, Cylar had decided that the standard-issue cot and locker for housing the homeless wasn't good enough. Housing Works' first ground-up facility would offer on-site health care services and apartments designed by Alan Wanzenberg, a famous uptown architect whose clients included Richard Gere and Mick Jagger.

On the 20th anniversary of the opening of the building, now named the Keith D. Cylar House Health Center (Cylar died in 2004), Wanzenberg and Andrew Coamey, Housing Works' senior vice president for housing, capital development, facilities, and construction management, discuss the enduring importance of the project.

Andrew Coamey: What Housing Works wanted to do was create an environment where you had a lot of services under one roof. At the time, the services that we offer here were not available in the community, weren't even available in the city. Bringing the services into the building made them very accessible to people. Being able to come down on the elevator, have breakfast, see a counselor, come up to the gym, work out, see a doctor, all in this beautiful physical environment, made it a lot easier for people to maintain their health.

Alan Wanzenberg: It was during the Giuliani administration, which was not sympathetic.

AC: That's a nice way of putting it.

AW: The support came ultimately from Alfonse D'Amato, who was a Republican senator from New York, who had a social connection to our original patron. D'Amato kind of shook the money loose.

AC: We got bonds from the state of New York. But the woman who was in charge of finalizing the bonds said she wasn't comfortable with the numbers. So Charles King, our president at the time, and Keith Cylar said, "Let's go make her comfortable with the numbers." A group of us went up to Albany and took over an office, with pillows and blankets and stuff like that. We had to evoke the spirit of ACT UP -- civil disobedience and direct action -- to make sure the vision these folks had for the project could come to fruition.

AW: The concerns were expense, and also "What are we doing all this for?"

AC: "Why do you need to build them something nice? They should be happy just to have a roof." There was a stigma attached to AIDS at the time, obviously, and homelessness. But another problem with finding a site for the property was Housing Works' belief in the harm-reduction philosophy. We were going to house active drug users here. We were not going to require people to be sober or take their mental health meds or do any of that before moving in, because you can't do those things if you don't have a place to live. Now there's a name for it -- it's called "housing first" -- but when we were thinking about it, it was just intuitive, and it was very controversial.

AW: We found a site that wasn't attractive to developers because of its strange shape, like the state of Oklahoma, with a panhandle that goes out to the street, Avenue D. But the site's eccentricities actually had some advantages. Because what we ended up with was relatively small floors, with about eight units on each floor. From a social point of view, that's a perfect size. With six to eight units, there's going to be three or four people who you become close with, and three or four people who you know. It wasn't dozens on a floor.

AC: The reception desk itself, because of the way it's sort of set back slightly, and that it's made of beautiful material, makes it not feel like it's providing security. It feels more like a hotel concierge desk, where you walk in and somebody greets you.

AW: It's not like, "I'm going to give you some crappy environment because you're all going to die in a few weeks or months." Going forward, the building would be celebrated and copied. That's why I think the story 20 years later is so interesting.

Excerpted from an interview with Wanzenberg and Coamey by Gavin Browning, an editor and the producer of Housing Works History, a multimedia timeline at HousingWorksHistory.com.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.

GAG ALERT: Gay adult film star bottoms out as Trump supporter