It was the dawn of disco in LA, and they were outcasts. When black people and queer people were turned away from the city's nightlife, Jewel Thais-Williams found her calling.

For over 40 years, Catch One offered a place of acceptance for those who needed it most. Once dubbed the Studio 54 of the west coast, Thais-Williams's establishment became a pillar for a community. From early days of harassment by local police to a time of despair during the AIDS crisis, it persevered for decades. Although its doors are closed, its legacy and that of Thais-Williams lives on through the many lives they affected.

They're the subjects of C. Fitz's newest documentary, Jewel's Catch One. For six years, Fitz befriended this amazing woman to tell her inspiring story. Now in the wake of the shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, the importance of queer spaces is as relevant as ever.

We caught up with Fitz and Thais-Williams ahead of the New York premiere of Jewel's Catch One at HBO's Urbanworld Film Festival to talk about adversity, opportunity, and legacy.

Out: When did you first discover Catch One?

C. Fitz: I discovered it in 2010. I was doing a piece on Jewel because she was being honored at a charity, and I donated my services as a director to do a two to three-minute piece on her. Within the first day of meeting her in April 2010, I said to her that we needed to do a documentary on her life. The more that I researched it over the years, the thousands of people that I met and the lives she touched, I knew that it was the right decision. How could such a life and all the work that she has done go without having some sort of documentation? Like starting the Minority AIDS Project and helping her community, it was an amazing journey, and the hardest thing was letting some of the stories go.

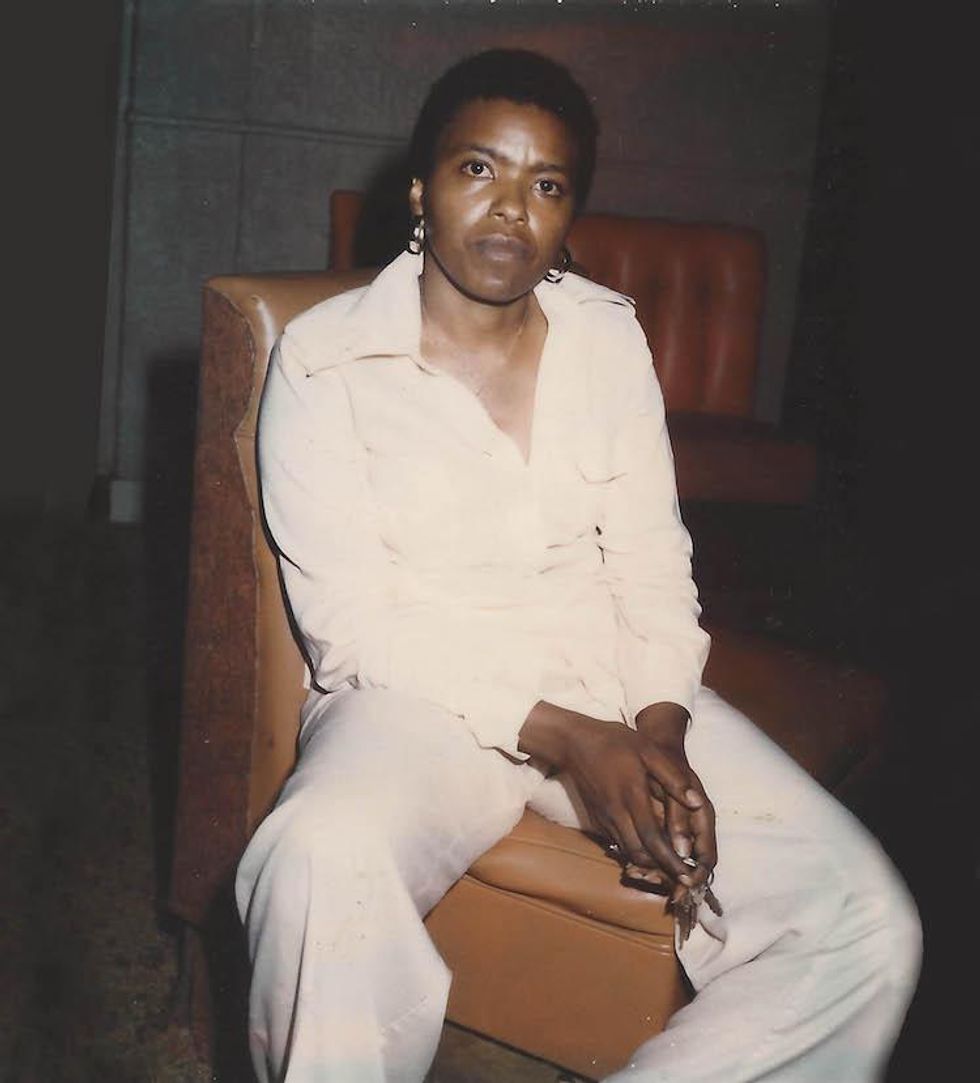

Jewel Thais-Williams during the early days of Catch One. (Photo courtesy of Jewel Thais-Williams)

What was the nightlife scene like before you opened Catch One?

Jewel Thais-Williams: I'm not an expert on that because I didn't go out that much. But I do know what pretty much existed then and why a need was created for the Catch to come about. There were mostly small neighborhood bars in the downtown areas. We definitely had to stay under the radar of the homophobic community that existed in those days. It was predominately guys at nightclubs around those times. Women had their separate club or two but they were definitely short lived. Their socializing pretty much generated around house parties and more intimate settings. When I opened Jewel's Room in 1973, which was a precursor to the Catch, it was the beginning of the disco era. The couple of big disco clubs that existed did not allow people of color or women to attend. So this was a chance for us to have a club in our neighborhood that was more or less comparable to anything you would find in other neighborhoods. We had the lights, we had the sound, we had the people, the clientele. Some gays and lesbians went to straight clubs and we acted like straight people while we were there. When we opened and people found out this was a club opened by a lesbian, they came.

You said you didn't go out much before. How did you come to the decision to open the Catch?

JTW: Truth be told, I knew there was a void. When I researched, I knew it would be successful. Prior to this point, I'd owned a women's clothing store, a boutique where we did alterations and things like that. Back in '70 and '71, there was this big recession and it cut deeply into the economy. Traditionally, when there is a strain on funds in a household, people stop buying and spending money on themselves. So I wanted a business that was recession proof basically.... There was a bar up for sale that was right across the street from the grocery store I worked at at the time, and a lot of the customers complained that they weren't welcome there. So I had the fleeting thought that maybe one day I'd own that bar, and everybody and anybody would be able to come. I used to pick up the LA Times and look at business opportunities in nightclubs and bars, and the last day I looked at one, an ad said that Diana's Club--which became Jewel's Room--was for sale. It was going to be a supper club but eventually it became a place that people could come and feel accepted, and then we opened the upstairs ballroom and started dancing.

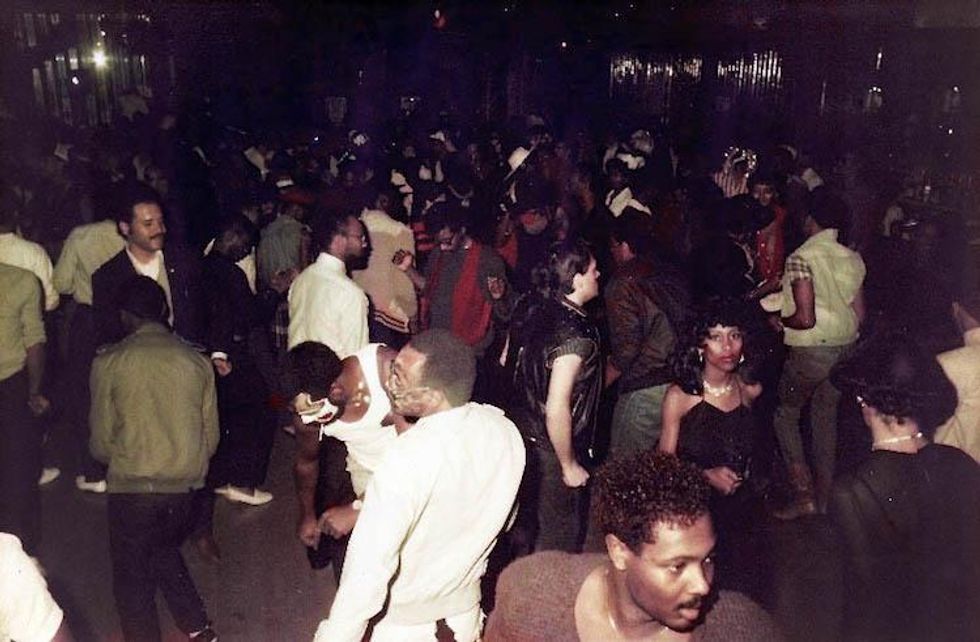

Patrons fill the dance floor at Catch One during the 1970s. (Photo courtesy of Jewel Thais-Williams)

You persevered through so much with Catch One. Was there ever a time that you wanted to give up?

JTW: No, not for that reason. The only time I was ready to give up was on my own personal journey. Other than that, it was about going when I was ready to go. And I wasn't ready because the need was there. When the AIDS crisis came along, another purpose was added. From that, the Minority AIDS Project came out of the Unity Fellowship of Christ Church. And later, Rue's House was born, which was a home for children with AIDS. What the Catch afforded me personally was the ability to do all these other service things I wanted to do. If that wasn't there, I couldn't do what was in my heart, which was to serve the community.

What do you hope this story can do for young black people, queer people, and women?

CF: We're very happy that it took six years because I think it's coming out at a really important time for us, for audiences, for LGBT people, for black people, for white people, for everyone in the wake of Orlando happening. The Pulse could have been the Catch. The Catch could have been the Pulse any given night in those 42 years. And we really hope that Jewel's life and her perseverance through a lot of hate and how she stood up to it time and time again, year after year, is a model for future generations and how they can be inspired to be like Jewel and to do something with their life on their corner of the world.

JTW: The legacy I'd like to leave is kind of two-fold. First, never underestimate the power of one person's desire to make a change and better their community. One leads to others. Many people came in and started organizations taking on the AIDS crisis and homophobia. I could not have done what I did without the involvement of others. The second part, there is an African proverb that says, "If the elders are lost, then the adults are lost. And if the adults are lost, then the children are lost." So I feel personally that it's come upon me and other of us elders. I have to be there. The elders are the ones that have to keep things together.

Jewel's Catch One screens October 8-9 at the BFI London Film Festival. Watch the trailer below:

Jewel's Catch One Trailer with dedication to #WeAreOrlando from C. Fitz on Vimeo.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right