Television

Gay TV and Me

How my life would be different if boys were kissing boys onscreen 40 years ago -- like they are today.

September 20 2012 8:34 AM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The boys were kissing, I was crying, my friend was laughing at me. It was the evening of March 15, 2011, and during that night's episode of Glee, Kurt and Blaine had finally kissed -- full-on, mouth-to-mouth, no "tasteful" cutaways. A friend called to ask what I'd thought of it; when I answered the phone, I could hear the noises of his weekly Glee get-together in the background, with some celebratory woo-hoos added to the mix.

My own mood was different. The boys' kiss left me in tears.

"So?" my friend asked. He knew that for years I'd been making the same tired complaint about the hypocrisies of pop entertainment: In an era in which network television could (and would) show raunchy three-ways, brutal serial killings, and graphic wartime violence, the only thing still considered "offensive" was to show two men kissing.

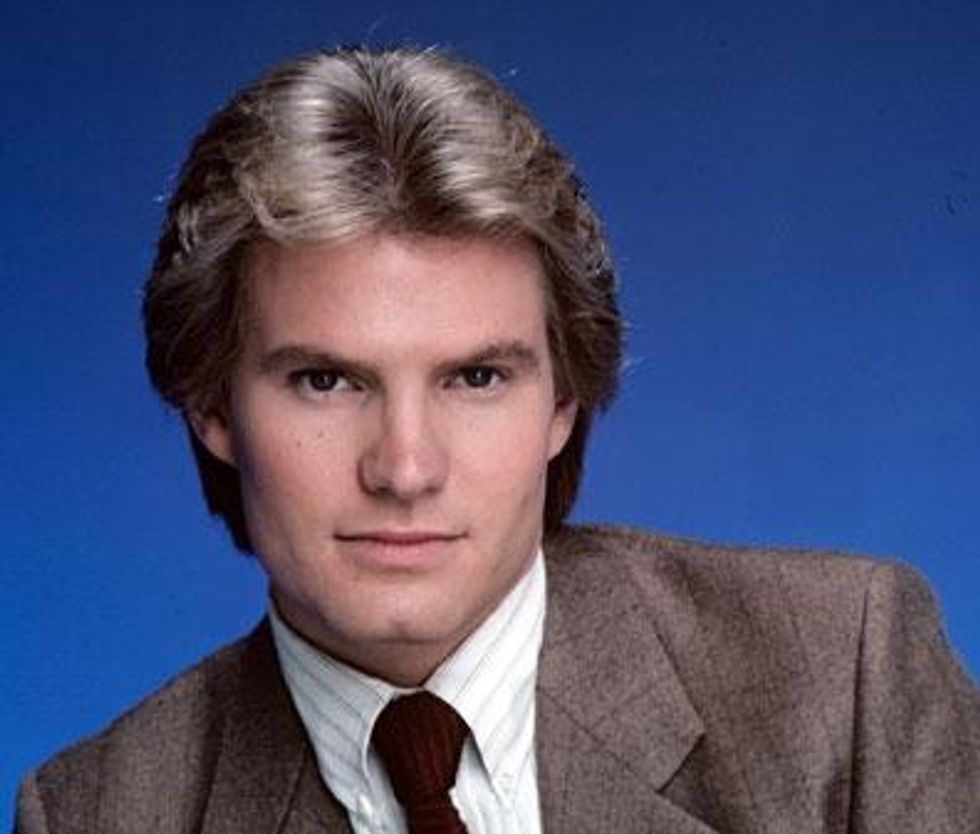

At the drop of a hat, I'd go into my satirical History of Gay Non-Kissing in Popular Culture spiel, lingering with special indignation on the climactic moment in Making Love, an earnestly sympathetic melodrama about an M-M-F triangle that came out in 1982, a year after I did; in it, the sexy, bee-stung, motorcycle-racing gay rake played by Harry Hamlin finally puts the moves on a prim, "questioning" doctor (Michael Ontkean) by... hugging him.

Things had got better since then, of course, and there had been other gay kisses on TV and in movies before the Kurt-Blaine lip-lock that night. But there was something special about the Glee kiss, something that made it feel like a fulfillment. The high school milieu, for one thing: Most of us begin our long histories of desiring in our early teens, and the longings that impel us then, and the fantasies they create, haunt us long afterward, often for the rest of our lives.

In the case of people my age, born in the 1960s, teenagers in the 1970s, before the tectonic sociological shifts of the 1980s that finally put gay people and their issues front and center in American culture, those longings were, more often than not, frustrated and ashamed. The idea of finding true love--mutual love--in high school was, quite simply, unimaginable. When, in the fall of 1977, I finally confessed my feelings to the swimming star I'd been crushing on all through high school, he crisply informed me that he'd never speak a word to me again.

My friend knew all of this, which is why we'd been following the developments in Glee for a while -- and why he exultantly called me the night the two Glee boys kissed. "So?" he repeated.

But I couldn't talk; I was sniffling. He giggled. "You're such a sap!" he said. I cleared my throat. "Fine, yes, I'm a sap." Then I added a thought I've often repeated since. "But I think my whole life would have turned out differently if that episode had aired in 1975, when I was 15, instead of 2011."

At which my friend, who's just a few years younger than I am, suddenly grew serious and said, "Yes."

It's difficult today to convey how utterly isolated you felt as a gay child growing up in the '60s and '70s. This isn't to say that it's not still an ordeal for many: As we know, the bullying and terror and torment are just as prevalent in many places. But one crucial thing has changed. The gay teen today has grown up in a culture that has become pretty casual about representations of gay people--in movies, TV, music, literature, advertising. And then there's the Internet: Access to information, discussion groups, and forums can at least give a gay youngster some notion of what being gay might be like and who's actually out there.

Part of the torture of growing up gay 40 years ago, by contrast, was precisely that there was nothing out there that you could look at and say, "That's me." If you secretly liked other boys, you were pretty much convinced that you were the only boy in the world who had these feelings about other boys--or that, if you weren't, there was no way to make contact with them. The only place to see another gay boy was in the mirror.

And what little there was on TV and movie screens was pretty scary. When I was six or seven, I was allowed to stay up late on Wednesdays--till 7:30, that is--to watch my favorite show, Lost in Space, a sci-fi updating of The Swiss Family Robinson. Already at some dim level I was aware that I was far more interested in the handsome dark-haired copilot, Don, than I was in his beauteous blond love-interest, Judy; much less dimly, I was aware that there was something "wrong" with the show's villain, the stowaway Dr. Zachary Smith. Pretty much every episode was generated by some conflict between the Robinsons, a space-age idealization of the all-American family, and the cowardly Dr. Smith. I couldn't know it then, but Smith was being played as a queen: mincing, fussy, his vocabulary too high ("Oh the pain! The agony!"), his motivations too low. (In every confrontation with aliens, he'd either collaborate or flee.) Even at seven, I perceived that he was, somehow, "gay"--this, even though I didn't really know what gay was.

A few years later, when I was 12 or 13, I had a better idea about myself, and was fervently hoping that the available options, once I grew up, were going to be more like Don and less like Dr. Smith. But the picture in the early 1970s wasn't a very hopeful one. As far as I knew, the only person who was clearly, identifiably gay on TV was Paul Lynde. We'd already grown to know him as Uncle Arthur on Bewitched. He was another of those crypto-homosexual characters from whom so many of us absorbed our first images of gayness: a mincing prankster in double-breasted plaid suits with exaggerated gestures and a hyena laugh. In Lynde's case, you didn't have to guess what his predilections were: As a perennial guest star on Hollywood Squares, Lynde could be startlingly open in his hints about his homosexuality. (Host, giving a clue: "You're the world's most popular fruit. What are you?" Lynde: "Humble.") Slightly more sinister to me, then, was the constant basso continuo of -- I didn't know the word then -- kink, the dark allusions that slithered and hissed just behind Lynde's humor. When given the clue, "George Bernard Shaw once wrote, 'It's such a wonderful thing, what a crime to waste it on children.' What is it?" Lynde replied, "A whipping."

And yet even as I puzzled over the thought that being gay was somehow tied up with being someone who enjoyed pain, I was also learning from Lynde. The endless indulgence in double entendre, the resort to coded language: I understood, these could be useful tools in a world in which forthrightness was impossible. There was also a lesson learned, perhaps, from Uncle Arthur: You could survive in a treacherous world by being amusing, by being an entertainer. What you felt, you hid, or you encoded; what you said must be witty, and harmless.

Who hasn't learned how to kiss from the movies? What I was desperate to see in the mid-'70s, when I was 14 and 15 and 16, was precisely what the pop culture wasn't ready to show me -- the images that all my straight friends had been casually absorbing all along: what desire and sex, kissing and lovemaking, happy coupling actually looked like. I literally had no idea what two boys holding hands, or kissing, looked like. As with so many gay teens, the only screen on which those images were flickering on was the overactive theater of my imagination. I often wonder whether the ease with which so many of us gay men adapted to the world of online desiring -- the porn, the hookup sites, the idealized images unencumbered by personality or responsibility -- wasn't the result of those early years of solitary fantasizing. When you spend your formative adolescent years in the bubble of your own erotic creations, reality can seem an intrusion.

There were two watershed TV events in the '80s; between them, they encapsulated the energies--earnest, seemingly unfulfillable erotic yearning, blithe camp fun--that animated us gay twentysomethings just then. The Disco '70s were over. Long hair and bellbottoms and Donna Summer were by now risible; Bruce Weber's Bear Pond and GQ were bringing back a conservative, pseudo-'50s aesthetic that was the visual expression of the Reagan ideal; and when I was a junior and senior at UVA, as the '80s began, we gay boys felt like we had it all, nothing to prove and on top of the world.

So there was a kind of loopy earnestness there. But of course a key element of Dynasty's appeal was the camp factor: The witchy glamor of Alexis -- in a way, a distant relative of Endora on Bewitched -- was irresistible. The notorious catfights between Alexis and Krystle, the cracklingly bitchy brunette and the ingenuous, blond, were a visual representation of the tense currents you felt as a gay man watching the show, caught between (as it were) Paul Lynde, the character you both reviled and learned from, and the nice, pretty normal boy you felt you were -- or, perhaps, felt you wanted.

Ironically, it was the representation of a distinctly un-normal boy--the aristocratic, troubled, beautiful, and doomed Sebastian Flyte on the Granada dramatization of Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited, exactly a year after Dynasty premiered -- that gave the representation of gays on TV the cachet that only literature, and the British, seem to be able to confer. Whatever else it did, Brideshead depicted the youthful gay love affair between Sebastian and his middle-class friend, Charles Ryder, without apology or embarrassment--as something to be expected in the normal course of things. This was a revelation. To us as we watched the show -- every Monday night for 13 successive weeks, telephones off the hook, fancy dinners kept warm in the oven -- its rich and lordly milieu, the liveries and plate, the hunts and balls, made the feelings we shared with its characters seem rarefied and elevated and special. It was the spring of 1982, gay love was finally on TV, and the future was as golden as the afternoon light in which, it seemed, the early scenes of Sebastian and Charles's love were always bathed.

By the mid-'90s, when I moved to New York City to write full-time, AIDS had made gay people more visible than ever before. But how? Not the least of the epidemic's cultural effects was to politicize the question of how gay people were represented in pop culture. No one, needless to tell, was ever happy. If a gay character was the tiniest bit swishy, people would be up in arms denouncing "gay stereotypes"; if a gay character was "straight-acting," people would be up in arms denouncing assimilation. Even after the most intense period of gay activism had subsided, the issues remained. For some, Will on Will & Grace was too square, not "gay enough"; but then, perhaps Jack was too gay. The central problem, it seemed to me, was that there can't ever be an accurate representation of gay people on TV, for the very good reason that there isn't a monolithic "gay person" to be represented.

But by then, when I was often writing about the arts and gay culture (primarily for this magazine, when it first started), it didn't seem to matter very much. Whatever you thought about them, whether they seemed "realistic" or not, there was a huge smorgasbord of gay characters, from "straight-acting" types to queens to fey boys to jocks, and of gay story lines, on TV, in all sorts of shows: from dramas to sitcoms to cartoons. (Even Homer Simpson got kissed by a man.) That, to me, has always been the point: Like anyone else surfing during prime time, you can at least get some sense of what the options might be. And one of those options, now, if you're a high school kid with a mad crush on another boy, is that you can let that other boy know how you feel, and that, instead of him turning away and never speaking to you again, he might just give you a kiss.

I can't imagine, really, how things would have turned out had I been able to watch such a thing in 1975, when I was aching to see what two boys kissing might look like. But I'm sure I'd have felt less like a freak, less like what I secretly wanted was utterly impossible. Well: I was born a generation too early. I like to think that 40 years from now, when the gay kid of 2012 is watching his gay kids watching gays on TV, no one will be crying.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right