I was attending my senior year of high school in 1982, a time when it wasn't quite as easy to come out as it is for some--and I emphasize some--folks today. Raised religious Catholic, I would endure the priest's annual sodomy speech--essentially saying that if you're gay and you act on it, you're going to hell. Or at least that's the way I interpreted it.

I was aware of my sexuality from my early teens, but I really started wrestling with it that last year of high school. Because I literally believed that I was going to hell, I became severely depressed. Back then, I felt like I couldn't tell anyone or ask for help. It got so bad that, during second semester, I actually tried to take my own life multiple times. Thankfully, I did not succeed.

Fortunately, during my freshman year at Georgetown University, I found something to distract me (and eventually release me, though I didn't known it then) from my torment. In 1983, Steve Jobs appeared in an article in Newsweek magazine, talking about this computer called the Lisa, which cost $10,000 and had a graphical user interface--the antecedent to the Macintosh. I remember being struck immediately by the way this guy talked and by his picture. He was handsome and kind of seductive, with intense eyes that invited you into his world of magic. Even though I was an English major, and didn't know anything about technology, I remember thinking Wow, that guy is amazing, and the Lisa is totally cool. I wish I could afford one.

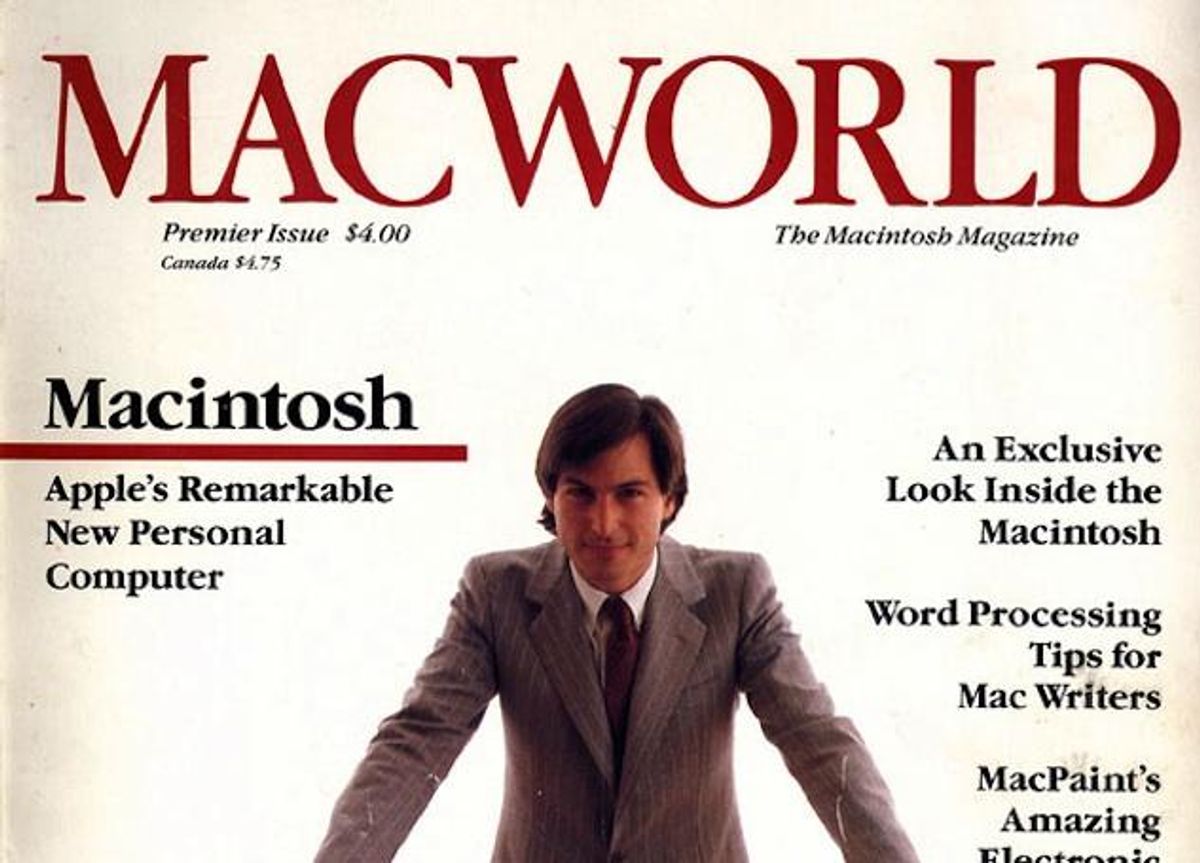

By my second semester in January 1984, Jobs introduced the Macintosh. Because he made it, and because it was like Lisa's little brother, I knew I had to learn everything about it. I read all I could about him and the new computer. Four times, I devoured every word of the first issue of Macworld magazine with Steve on the cover, looking forward with his arms spread open across three Macintoshes, saying, "Join me in Wonderland."

Finally, the day came that changed my life forever. I went to a computer store in downtown Washington, D.C., to see my first Mac in person. At first the shop appeared deserted, until I rounded a corner and there were about 30 people in a cluster, of course huddled around the only Mac on the floor. I waited patiently for my turn. When I sat down, I drew a tree in Mac Paint and printed it out on a companion Apple ImageWriter printer. This was the first time that what you drew on the screen would actually print out and look exactly the same. This was big. All of a sudden, I just knew this was important. This was going to change the world. I wanted to meet all the people whose signatures were molded in plastic on the inside of the Macintosh: the actual creators, including Steve. At that point, I became obsessed.

A professor at Georgetown had been encouraging me to do something more challenging academically, and I applied to transfer to Yale. However, at least half the reason I switched is that Yale was a member of the Apple University Consortium, a genius marketing program Apple set up at some of the fancier schools, where you could get up to 60% off a new Mac which otherwise retailed for $2,495 ($5,177 in today's dollars). In hindsight, that program affected me and so many other LGBT folks who would end up in Silicon Valley, giving us affordable access to this machine that would open up our worlds. Indeed, the program's slogan was "Wheels for the Mind." I was so smitten, I even drove to school a couple days early to get in the August-vs.-September Mac allocation.

Since I was a transfer student at Yale, many students had already found their friends as freshmen. The school workers were on strike and teachers wouldn't cross the picket lines. It was an inauspicious time to arrive. Unlike Georgetown, I had a hard time breaking into the social scene. I was lonely and very much still closeted. In true made-for-TV-movie fashion, I remember I would stand and hide outside in the bushes and look in through the window at the gay students' meeting, but I was unable to bring myself to open the door and go in. But my brand new Mac (finally!) gave me this purpose and it gave me something to do with all this energy and passion. I really believe that sublimating my libidinal energies into the Mac is why I have the privilege to do what I do today. If I were out dating at Yale in 1984, the year before Rock Hudson was on the cover of Newsweek and mass hysteria broke loose, I wouldn't have known any better. And, at least now, hurting myself was the farthest thing from my mind.

I befriended Philip Rubin, who founded the Yale Mac Users Group (YMUG), and became one of the five most active members, writing and publishing their newsletter, still laying it out using scissors and rubber cement. It's hard to imagine how exciting it was to be involved in the beginning of something new, where new breakthrough software and accessories were coming out: Pagemaker! The Apple Laserwriter! Excel! Back then it was possible to know about every single thing in the Mac universe, and we did.

I got so into the Mac and YMUG that I barely did any schoolwork and ended up dropping out. But before I did, Philip encouraged me to try out a new toy: a 300-bits-per-second modem, thousands of times slower than today's Internet. With that, I was able to go online using CompuServe, an early text-only online service. To my great excitement, I discovered a gay and lesbian section with postings and information and people talking to each other: a real gay community to belong to from inside my closet. I sent a message to the gay system operator that said, "I'm gay, and I'm struggling." He replied with information to read, books to buy, basically telling me, "You'll be OK." This was the first gay person to whom I affirmed "I'm gay," and the first person to reassure me. This was huge. On a side note, I remember thinking, I wish you could have a Mac user interface to access online services, which is exactly what the web came to be, yet another staggering consequence of the Mac.

Once I left Yale, I sold Macs for six months (easy) then went to Paris for six months, ending up writing for Infomag, a French Macintosh news magazine. When I returned to the states, I was invited by Apple to attend their sort of pre-Macworld Expo called AppleWorld conference to be held in San Francisco. This is where my eyes were really opened for the first time. At the event, I saw all these handsome gay men, guys who seemed to be so comfortable with themselves. I felt like I really belonged here in three senses of the word: in the Bay Area, in the Mac world, and in the gay community, a Venn diagram in which the three circles overlapped. On the spot I resolved to move out as soon as possible. (My joke is that I came out to Silicon Valley, both literally and figuratively.)

Since I hadn't finished college, I couldn't work for Apple as they required a degree. So I joined a small startup, SuperMac, who sold the first fast hard drives for Mac Plus. (20 Mb only $1299!) At the same time, I worked up the nerve to move in with three out gay guys, who immediately took me under their wings (One, Marq, a brilliant computer scientist from Stanford, was another Apple Consortium baby. Another, Tom, who was a recovering alcoholic living with HIV, was my coming-out Yoda. Unfortunately he died just before AZT became available.) Though, except to a few, I was still in the closet at work, my career brought me face-to-face with all these gay and lesbian people in the Mac industry. I realized that I finally belonged. Slowly, between 1986 and 1988, I started coming out to family and friends. The hinges started to fall off the closet door: By 1988, I brought my boyfriend of the moment to wait outside during my final interview at my second job, Farallon, also a Mac company. (Networks! Audio into a Mac! Screen sharing!) Since then, I've been lucky enough to be out both personally and professionally.

Inspired by Queer Nation in 1990, I would go on to co-found Digital Queers--which helped to train the LGBT activist community about using technology and raised funds to buy computers (Macs!) and modern technology for gay and lesbian non-profits, like the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, PFLAG, and GLSEN, among others. We raised the money at parties held in the evenings of the Macworld Expo, the massive trade show and annual meeting of the faithful. LGBT Apple employees were among the first trainers and donors. Later, I created PlanetOut, which provided an online community for LGBT folks, with community, news, entertainment, sports, travel, and more. The company proved (much like Out magazine) that a gay corporation (run on Macs) could attract venture capital, corporate investment, mainstream advertisers, and millions of members. But that was not why I started it. Though this might sound mawkish or overly earnest, I wanted to help teens who were like me way back in high school.

There are so many parallels and links between the Mac and gay communities. The Mac world was one of creativity, ideas, and energy. Most of the world used a PC, with just a small amount of Mac users (at the time, almost exactly like the ratio of straight to LGBT people). Mac users often faced mockery, harassment, and other forms of opposition just to use a Mac in their place of business. (Seriously.) Back then, we found surprising statistics showing that gay and lesbian people were up to three times more likely to own a Mac than a PC. And I promised you, back then (and now) there was a higher percentage of LGBT people working in the Mac industry than in others. Hey, and we care about design.

Apple was also an early and consistent leader in gay and lesbian rights. They had an equal opportunity policy from very early on, and one of the first companies to have domestic partnership benefits (engineered by Elizabeth Birch, former HRC executive director, but then an Apple litigator). More recently they became one of the very the first companies to have a trans-friendly anti-discrimination policy. Apple was the bellwether. What Apple did employee policy-wise, other Silicon Valley would inexorably follow. Apple was the bellwether. Queer Apple employees, led by Bennet Marks, founded Apple Lamdba, an officially sanctioned group that helped bring the trans protection among dozens of other accomplishments. Apple also donated $100,000 very publicly to defeat Proposition 8 in California. And I know have it on good authority that as a person, Steve was a great friend to the community, both on principle and, more importantly, to the gay people in his life.

This journey, of course, never would have happened without Steve Jobs and the Mac and everything that came after (the World Wide Web was built on a Next machine, also a Steve creation). Because of his inspiration, his passion, and his energy for not only the products and his team at Apple, but for the community he inspired around them, I really and truly believe that he and the Mac saved my life, and, at a minimum, gave me purpose, meaning, and belonging. Though I only met Steve a handful of times, I felt and still feel a strong personal connection to him that, I'm aware, defies reason. When I found out he died, I felt physically ill and, of course, sad for him, his family, his friends, and his co-workers. I also feel sad that the world that will not benefit from 20 more years of his brain.

If you've been reading other Steve remembrances over the past days you know my story is not unique--it's just one of millions of such stories of the people he touched, and at least some of those yet to be told may have a LGBT twist.

The Compuserve system operator I emailed from my Mac computer at Yale turned out to be Deacon McCubbin, the founder of Lambda Rising bookstore in D.C., the largest LGBT bookstore in the country. In 1996, I was able to go to his bookstore and thank him in person and, later, in print for what he did for me way back in 1984. Thought I can't tell you in person, thank you, Steve. I will forever be grateful, and you will always be my hero.

Rielly is Community Director for TED Conferences. He still reads the Mac blogs daily.

If you have a similar story and would like to share, we'd love to hear it. Email us at letters@out.com.