Photography by Yi-Chun Wu

To be clear, Wendy Whelan is not old. She's 48, and on stage looks a decade younger. She also moves freely and fluidly and can easily send her leg over her head, which is generally not what we expect from someone nearing the half-century mark. Last fall, Whelan retired from the New York City Ballet, where she had danced for over 30 years and earned her place as one of the great contemporary American ballerinas.

This week, Whelan took to a smaller stage in a different context, as the muse of four men in a show called Restless Creature, which she clearly is. Whelan handpicked the choreographers -- Alejandro Cerrudo, Joshua Beamish, Kyle Abraham, and Brian Brooks -- who each created a short (10 to 15 minutes) duet, and danced it with her. The project premiered at the Jacobs Pillow Dance Festival in 2013 and was supposed to be seen in New York last spring, but was postponed when Whelan suffered an injury. So it's not a true post-retirement debut, but it was conceptualized with life after NYCB in mind. (It's currently being performed at the Joyce Theater in New York City through May 31.)

And the fact that Whelan is performing so soon after her final bow at Lincoln Center serves as a nice statement that retiring from dance doesn't mean disappearing entirely, nor does hanging up your pointe shoes preclude you from experimenting elsewhere. Much is made of dancers' short careers, particularly in ballet: you start training at age three and retire by 30 with a broken body and an unclear professional future. Whelan defies this assumption, though her longevity is too rare.

But it's not just the dancer who pays the price of age - the art is affected as well. Ballet is, after all, largely the dramatization of relationships. Even non-narrative, abstract ballets often place two partners (usually male-female) in a web of physical signifiers that represent all the push and pull, vulnerability and trust of a relationship. Often, these duets skew toward the romantic. And when they require virtuosic feats of the body, it's usually left to lithe twenty- or thirty-somethings to pull them off. Young, fit, heterosexual couples: pretty to look at, but also a pretty limited representation of relationships, considering what's out there.

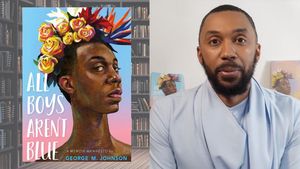

Wendy Whelan with Kyle Abraham

Wendy Whelan with Kyle Abraham

Restless Creature doesn't radically challenge this idea (it's still male-female and everyone has a great body), but the pairing of Whelan with the four lads -- all of whom are younger than she -- gives refreshing shades of nuance to the partnerships. Each piece has its own mood and dynamics: Cerrudo's Ego Et Tu contrasts his human earthiness with her angelic lightness; Beamish's Conditional Sentences casts Whelan as a conspirator to his playful antics; Abraham's The Serpent and the Smoke allows for a darker, confrontational exchange, while Brooks' First Fall makes him a poignant prop on which she constantly relies and revives.

None of the duets exhibited the tell-tale signs of the dance romance: the longing looks, the tender touches, the passionate leaps and lifts. They certainly could have gone there, and perhaps that'd be worth celebrating as well: a younger man in pursuit of an older woman, ballet's Ashton and Demi. (There's precedence for this -- most famously in the iconic artistic partnership in the 1960s and '70s between Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, 19 years her junior.) But the choreographers here seem interested in platonic partnerships. And while it may be impolite to dwell on Whelan's age, the fact of it allowed for greater possibilities in interpreting the relationships and interactions on stage. It also added something soothing and serene to each work -- maybe we can call it wisdom.

Of course, there are whole segments of the dance community who embrace dancers of all ages and bodies types and are more interested in using dance to address social issues than amorous ones. (It tends to be called "Downtown dance," however imperfect the term, and a recent dance highlight was a performance by Steve Paxton, a 75-year-old forefather of this brand of dance.) But even when smart young ballet choreographers -- Justin Peck at NYCB comes to mind -- create complex and compelling non-romantic social worlds onstage, these worlds are inevitably filled with a very narrow range of bodies -- young and toned -- which limits its potential allegorical reach. Kind of like Hollywood, actually.

And though Modern dance in many ways was born in opposition to ballet, plenty of contemporary dance companies and choreographers from that tradition have maintained ballet's rigorous aesthetic standards, featuring exclusively the young and the beautiful and implicitly championing the virtues of juvenescence and dismissing any hint of the threat of aging. Especially in ballet, young love still reigns. But with Restless Creature, Whelan, for the past several decades a pillar of ballet in this country, steps beyond ballet's suggested expiration date and demonstrates that lifelong curiosity and experience are as valuable artistic tools as pirouettes and penchee.

Through May 31, Restless Creature is at the Joyce Theater in New York City.

Wendy Whelan with Kyle Abraham

Wendy Whelan with Kyle Abraham