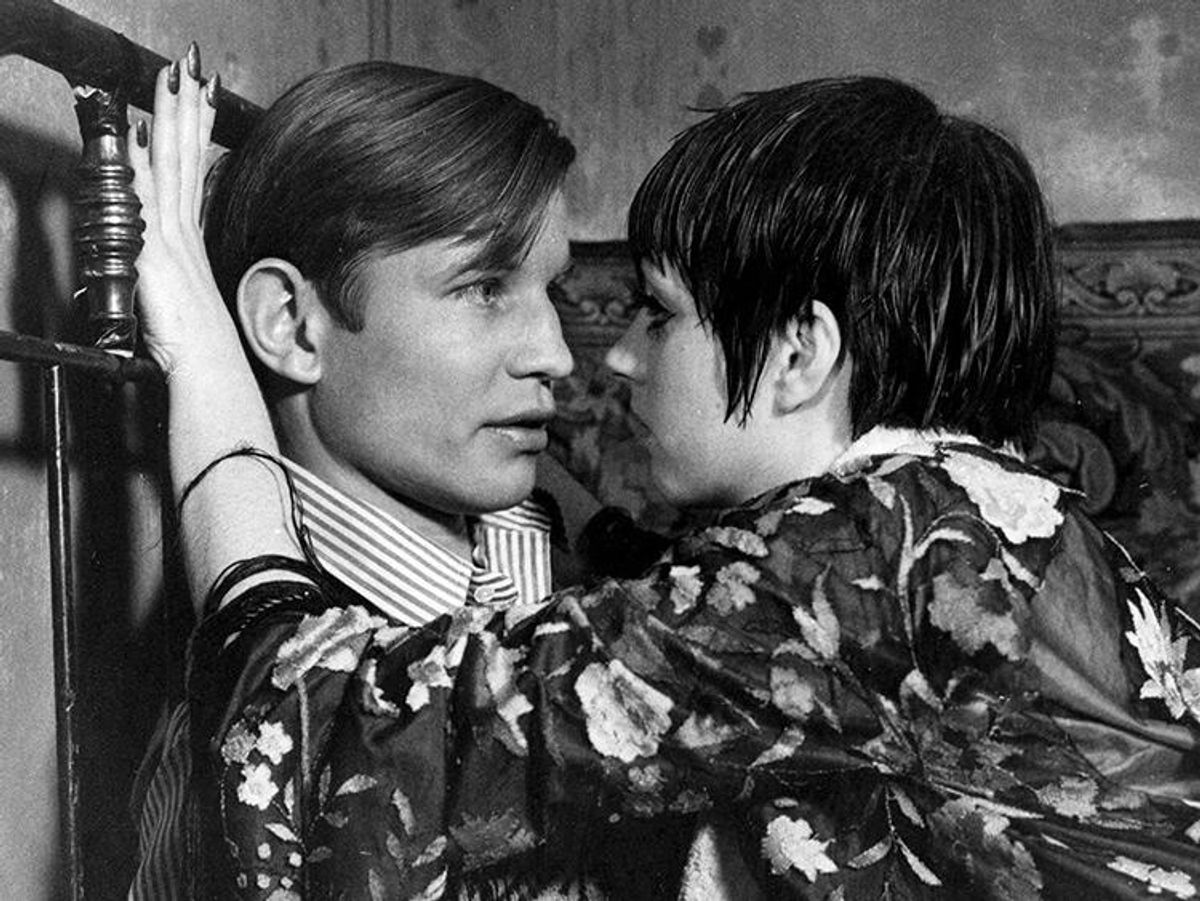

Although Cabaret, the 1972 hit movie-musical, gave Liza Minnelli her icon status, it featured an equally important star: Michael York, who portrayed Brian Roberts, an English scholar thrown into the sexual-artistic-political turbulence of post-WWI Germany. The role was based on gay author Christopher Isherwood's memoir Goodbye to Berlin (also an influence on Truman Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's), and York made his character's ambiguous coming out appealing and timely.

When Minnelli, as American expatriate nightclub singer Sally Bowles, asks him if he sleeps with girls, York's Brian skirts the issue by describing his past heterosexual experiences as "disasters." York was already a standout in several notable European films (including Joseph Losey's bisexual tease Accident), and director Bob Fosse used his guiltless, fresh-meat innocence to assuage the sexual fears of post-Stonewall American audiences.

Cabaret successfully changed conventional attitudes toward sex by introducing queerness in a historical context. It used the era of German Expressionism better than the recent film The Danish Girl even though Fosse's pervy attraction to what Minnelli's Sally called "divine decadence" softened moviegoers' acceptance by allowing them to enjoy his bohemian characters while feeling superior to their Nazi-era fate.

Stepping back, but moving forward, Fosse's film centers on Brian and Sally's menage a trois with a rich and experienced baron, Maximilian von Heune (Helmut Griem, with a sinister mustache and appetitive gap-toothed smile). The pair is drawn to Max's money, but Brian is particularly seduced by his own personal curiosity. He returns Max's devious sly glances, and their hands touch when Brian lights Max's cigarette. Cabaret avoids showing two men kiss, yet the movie's songs and drama about social collapse center on sexual transgression. "Two Ladies," sung by Joel Grey, as the Kit Kat Klub's freaky emcee, pantomimes a bisexual dalliance while Max entices Brian and Sally with an African safari, a racially coded attempt to loosen their sexual inhibitions.

This was how post-Stonewall Hollywood taught queerness: fitting it into traditional storytelling about taboo-breakers who would try anything, and, most significantly, idealizing it in York's blond, blue-eyed naivete. "I was right. Blue is your color," Max says when tossing Brian the gift of a blue cashmere sweater. York blinks like a trapped animal. Brian's sexuality is found out; he can't deny his nature.

He comes out coyly: He tops Sally's boast about fucking Max with the classy riposte "So do I." This reveal, delivered in York's elegant, purring alto, was less than a surprise to post-Stonewall filmgoers for whom York was already a sexual icon. In the 1968 Romeo & Juliet, director Franco Zeffirelli presented him as a dashing, dark-haired Tybalt--an undeniably erotic, possibly gay figure in body-clinging tights and a colorful codpiece.

York's role in Cabaret redeemed one of his past aberrations. In 1970 he portrayed a murderous, bisexual gigolo in Something for Everyone--the first film directed by Broadway legend Harold Prince. That film's new Blu-ray release by Kino commemorates an embarrassing moment in the evolution of Hollywood candor and tolerance. The filmmakers' sophistication--and York's winking appeal--turns against them through the story's snickering, satirical equation of queerness with depravity.

Ironically, Something for Everyone is not for everyone. It wasn't a popular success, in part because its love-quadrangle plot (York beds an entire family of Bavarian aristocrats whose fortunes have faded after WWII) is even more darkly sinister than Cabaret's. The film's heartless decadence turns out to be rather unfunny when York's character equates sexuality with distrust and horror. It taints the kind of innocence shown by Cabaret's two young lovers (Marisa Berenson and Fritz Wepper) who ask a fundamental question about sexual attraction: "Is it love or is it mere infatuation of the body?"

That question is always a dilemma for gay filmgoers who are seduced by an actor's charms. Michael York's on-screen trysexuality is notable because it creates a sense of personal identification and wonder.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays