In a new memoir, Brad Gooch recalls gay New York in the heady and turbulent 1970s and early ’80s, a time of promiscuity and elebration that quickly turned to fear, paranoia, and anguish.

April 14 2015 5:29 AM EST

April 14 2015 5:30 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

In a new memoir, Brad Gooch recalls gay New York in the heady and turbulent 1970s and early ’80s, a time of promiscuity and elebration that quickly turned to fear, paranoia, and anguish.

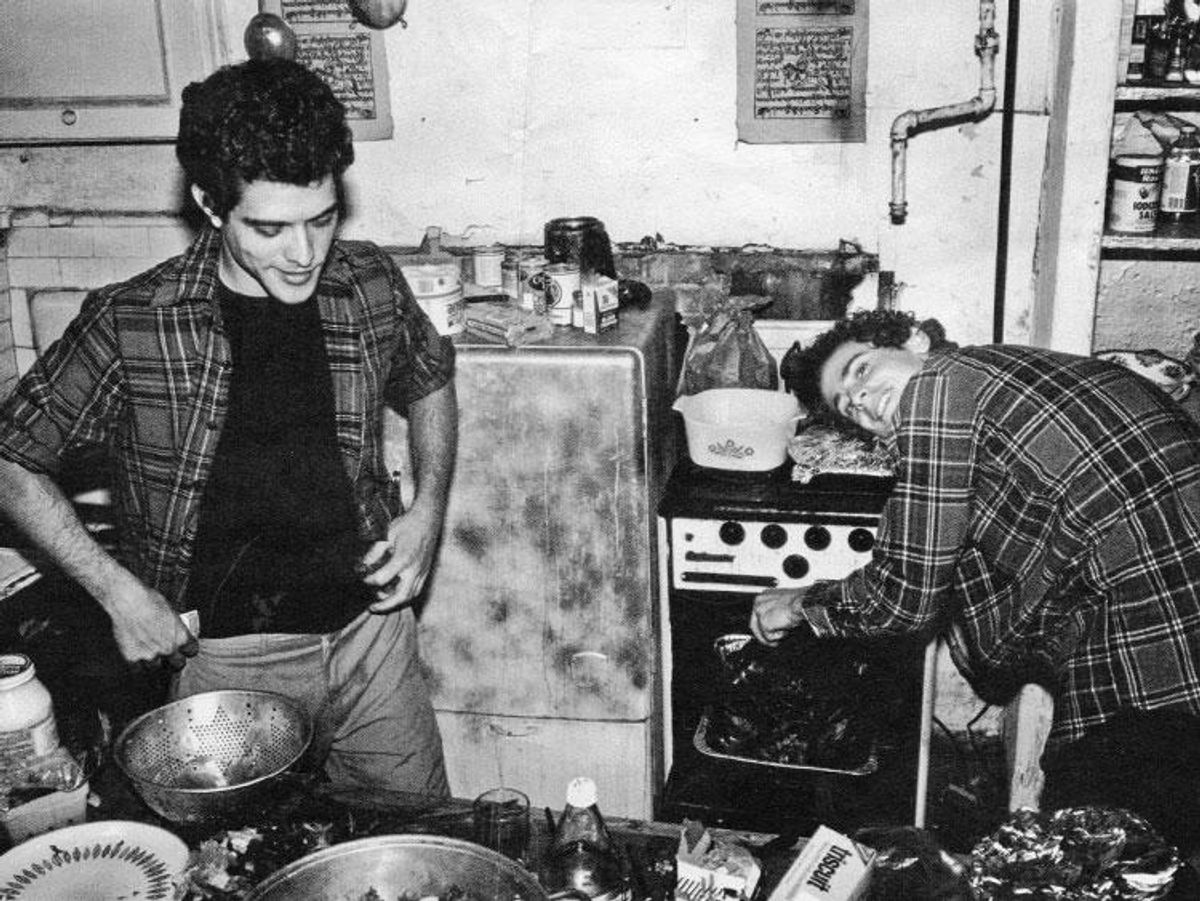

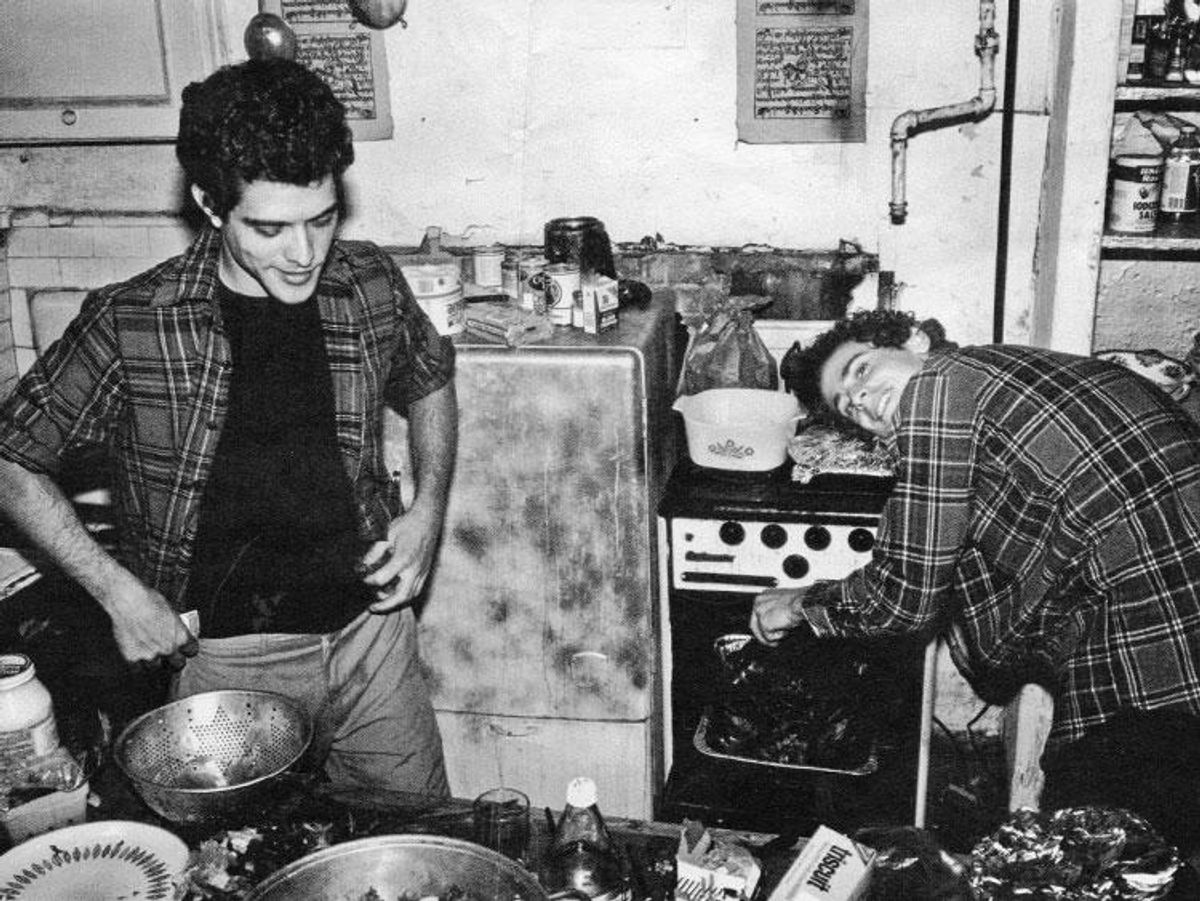

Courtesy of Brad Gooch. Brad Gooch, left, and Howard Brookner in 1979. "In the kitchen of our first apartment together, we look like each other's doppelganger," Gooch says, "both in flannel shirts, and matching curly locks."

Smash Cutis the clear-eyed and elegant love story of two young men -- the model and writer Brad Gooch and the filmmaker Howard Brookner -- who met in 1970s New York. Here, Gooch recalls the period when the specter of AIDS, which would eventually steal Brookner from him, began to cast its long pall over New York's gay community.

The 1980s was a turn of the page: careerism became important, along with muscles and money and celebrity. The more we encountered the serious depths lurking in the epidemic that we had been trying to deny, the more superficial and driven by stress we became. A new permutation, gay gyms, began, too, with Chelsea Gym, all gray and chrome, and a new kind of clean-cut muscle guy. We hadn't been too interested in our bodies in the seventies, but now we were. A veritable lifeguard type named Tom McBride was the class president of buff young men, and highly promiscuous. He was a photographer and an actor who'd been in Friday the 13th. I flirted with him some, and he came over to the room one afternoon and nailed me on the rug. I don't remember the event because the sex was so singular but because that was the last of its kind for me.

Soon after my afternoon with Tom, I began having night sweats, as I heard of more cases of friends and sex partners developing AIDS. When I told my therapist, Sister Mary Michael, she suggested I remove the blankets, which I did. The sweating subsided, but not the panic of thoughts and fears. I discovered that I was a very fearful man, not at all the steady sailor I'd figured I was, as I was faced with a historical-class horror. So I began a regimen of what would later be called "safe sex" that bordered on muscle-deep emotional frigidity. I put my enthusiasms away, after a decade of cultivating them.

Like Howard, my career was proceeding more briskly now, a response to the prevailing winds of the times. Our three-way phase slid into separate beds, though sometimes that bed was still our queen size in the Chelsea Hotel. I didn't feel any pious obligation to keep Howard's indentation in the mattress vacant during his travels. By the time he returned, sort of, the practice was mutual. Probably the most significant of Howard's American romances was with a young actor, let's call him Sean. He met Sean one night at the St. Mark's Baths, while I was away somewhere. The Baths were all about men walking around in white towels, with keys on ankle bracelets for rooms (more expensive) or lockers (cheap). Howard's attention was caught by this dashing 21-year-old guy who was striding around, coloring outside the lines by being fully dressed in jeans, a flannel shirt, and shoes. Just as striking, and pretty, were his face and eyes and bone structure, very much a young actor of the ilk being pushed forward in the eighties in films full of young male actors, like The Outsiders. Sean, who spoke with a barking Boston street accent, aspired to do film work, which added electricity to Howard's fantasies. Sean fit, as well, into his professional plans. Becoming a feature director was his current desire, and so he had become interested in actors and actresses, a perfect fulcrum for his love of beauty and for his ambitions, which had lately turned more Hollywood.

For both of us, this elbow period in our lives -- an elbow in the decade of the eighties as well, a little crook before the dark truth was revealed -- was filled with manic work that seemed exciting and preoccupying. I segued from porn reviews to book reviews for The Nation, through an editor, Duncan Stalker, who died of AIDS -- another check -- but not before he went to a new magazine, Manhattan, inc., reporting on the pulse of conspicuous moneymaking, frantic moneymaking, in Manhattan, featuring Donald Trump and other such recently minted types. He hired me to write a review of Martin Amis's novel Money -- on theme -- that led to my first magazine profile, of club personality Dianne Brill, who also designed a line of clothes.

What felt like two minutes later I entered the offices of Tina Brown, the new editor in chief of Vanity Fair, a magazine title and concept that got the serious joke that was being told right then with such great interest. Here was my version, the magazine version, of the Hollywood Sirens that Howard was hearing. Thirty-three years old when we met -- a year younger than I -- Tina was tingle-inducing, with her Princess Di short bob and her British lilt, and her embodiment, in her magazine, of an unabashed fascination with power and buzz in all its Reagan-era manifestations.

Howard was on his own trajectory, arcing toward his version of adrenaline made visible. He sketched out a few film scripts, hoping to interest PBS American Playhouse in producing a feature film. Burroughs's Junky was one possibility; a Stephen King story another; and a film version of James Purdy's Southern Gothic novel, Eustace Chisholm and the Works. I was scrunched in my apartment, finally turning all my modeling memories into a novel. I had such a hard time with my short-story attention-span that I tied myself to my desk chair to keep at it, else I'd find myself wandering the apartment, or the neighborhood, before I'd start up short and remember that I had been in the middle of a paragraph.

Our lives had been simpler and more straightforward when we were starting out, living together a few steps from the Bowery. Howard's complication was that he was now passing for straight, playing Hollywood as it lay, or so he insisted. Sean was still around, slouching, with allure, but he was an actor, and so he was dedicated to being straight, too. I could never be sure. Howard also had an affair going on with an extremely beautiful French actress. I would find Polaroids of her covered only in a white sheet, lying in bed -- scattered about the loft, as if blown in from some French nouvelle vague film. I knew from modeling the weird sensation of one step forward two steps back on the gay issue -- adapting to a closeted or bisexual life after having been openly gay. Now the culprit was supposedly Hollywood, but of course the unlabeled shadow of AIDS had to be factored in. We were being "straight" or "normal," Hollywood or Madison Avenue, madly trying to pedal ourselves away from the stigma of a disease, and its accompanying gay world and bumpy life.

But that unwitting charade -- not entirely a charade but a sort of coincidence concocted from subtle hints, and shifts, and whistles in the dark -- did not work. The disease began to catch up with us. And then I saw it. Well, I didn't see it. I heard it first. I was walking on a drizzly fall day, crossing Sixth Avenue and then Greenwich, passing by the Jefferson Library, with its gingerbread tower. I was thinking about the Women's House of Detention, which was before my time but I believe had been situated in that triangular lot -- now a garden for the library. Women's catcalls had supposedly been screeched down from the windows on hot summer days. Right then I heard a howl. I looked across the street, and across that street was a tall, thin guy in his thirties or so, with wiry spectacles, his skin as gray as the day. He had howled, and now he was bawling, and the tears were running down his cheeks like rain, more rain, and in his left hand he held tightly a pharmacy prescription, and I knew that he had just received his diagnosis and that now he was on his way.

Adapted from Smash Cut by Brad Gooch, published by Harper.