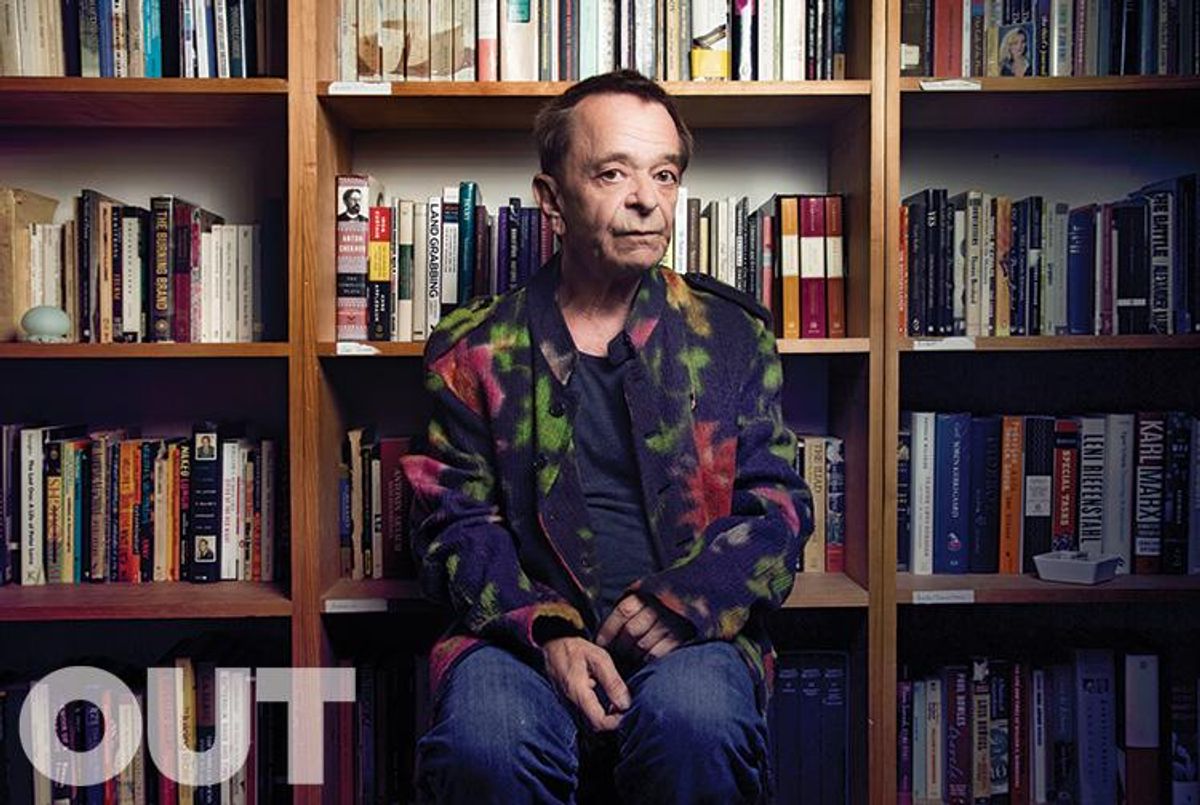

The blunt, acerbic honesty of Gary Indiana has turned him into one of America’s most illuminating journalists. His 'first and last' memoir builds on that legacy.

August 24 2015 11:00 AM EST

August 27 2015 10:10 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The blunt, acerbic honesty of Gary Indiana has turned him into one of America’s most illuminating journalists. His 'first and last' memoir builds on that legacy.

Photography by M. Sharkey.

In the late 1970s, after publishing "a few things, in some obscure places," an almost 30-year-old Gary Indiana abandoned Los Angeles for New York City and began writing for several downtown publications, ultimately landing in 1985 at The Village Voice, then at the zenith of its influence. The earliest of these pieces were more or less straightforward critical essays: on Irving Penn, Paul Schrader, and Gilbert & George (whose work, Indiana concluded, with his characteristic ability to scalpel away pretension like a path-ologist peeling back a cadaver's face, "shows what artists can do without any urgent insights"). But as time passed, the writing became increasingly based in reportage, on subjects ranging from Branson, Mo., to Euro Disney, from the 1992 New Hampshire Democratic primary to the adult film industry at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Indiana described these sojourns in the introduction to the 1996 collection Let It Bleed as "staged collisions of my sensibility with phenomena plainly alien to it," but what emerges when one reads through the essays is how not staged they seem, how strange yet seemingly inevitable the encounters were between this fey, gay, ferocious genius and the discreet charms of the bourgeoisie. Like the greatest of the New Journalists -- but above all Joan Didion, who must be considered one of his muses -- Indiana always packed his "sensibility" in the same bag as his cigarettes, bourbon, and Basis soap, but he never allowed his biases to overwhelm his capacity to describe, with blunt, acerbic honesty, the things he encountered, no matter how alien they might seem to him.

The resulting clashes were not so much jarring as illuminating -- it's-funny-because-it's-true/it's-funny-because-it's-sad -- and 20 to 30 years later the essays still glow in the minds of New Yorkers of a certain age. "You picked up the Voice in those days, half expecting it to bite you," the writer Jim Lewis says, "and half the time it did. And when it did, it was usually Indiana who had blood on his mouth." Or, as Indiana wrote in a review of Herve Guibert's To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life: "A high level of artistry is the only lastingly effective form of propaganda." The sentence, veering effortlessly from Oscar Wilde to Karl Marx, part old Hollywood, part punk rock, is quintessential Indiana. It was a tone that not a few gay men were trying to pull off at that particular cultural moment, but Indiana's was distinguished from lesser efforts by a rapacious intelligence that was as wide-ranging in its references as it was relentless in its acuity and refusal to be taken in by good intentions, let alone success or acclaim -- either his subjects' or his own. Unlike many of his peers, Indiana wasn't split between the establishment and the avant-garde: He knew them both, and felt no need to kowtow to one camp, one style, over another, nor to be consistent in his admiration or loyalty. His description of H.R. Haldeman's posthumously published diaries has more than a bit of resonance with his own approach to writing: Haldeman, he wrote in 1994, "owes a little to James Boswell, a bit to Cosima Wagner, and quite a lot to Joseph Goebbels. Swirling in decaying orbit around a black hole, he too mixes the sublime with the tawdry, the monumental with the petty, the public gesture with the private tick." Goebbels's black hole was Hitler, of course, whereas Indiana's is the whole modern world, "the wreckage of a century I lived through the second half of," as he describes it in his second essay collection, Utopia's Debris, "a century of false messiahs, twisted ideologies, shipwrecked hopes, pathetic answers."

"There are a lot of people writing these days who try to sound like Indiana," Lewis says. "I don't know if they realize they're imitating him or not, but they all come up short. They sound merely snotty where he was savage; bright, in a common sort of way, where he's deeply erudite; play-acting where he sounds like he's already pitched himself off the edge, and wants only to get some truths out before he hits the ground." But though you approached a new Indiana article in sweaty-palmed anticipation of gleeful, unrepentant schadenfreude, you were almost always treated to a surprising dose of empathy as well. In 1985, for example, when the art world rallied in defense of Tilted Arc, Richard Serra's 120-foot-long sculpture that blocked the sidewalk in front of New York City's Federal Building from 1981 to 1989, Indiana broke with his presumed peers to take the side of the office workers, pedestrians, and homeless people inconvenienced or offended by an "egomaniac's prefab sculpture." It is these people, Indiana argued, who "occupy real space, as distinct from the space of idealistic projections, utopian fantasies, and masturbatory empires. They are the brothers and sisters of the people huddled in the halls of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building waiting to be photographed for immigration documents. They couldn't care less if Richard Serra's contract with the GSA is abrogated. Their contract with anything has been severed at the nerve by the government Richard Serra expects to do the proper democratic thing." Of the '92 primary, he concluded: "Any candidate worth voting for, however hard the times, ought to offer people an appeal to their better natures, as well as to the part that eats. Nobody did." Twenty-three years later, a new election looms like a dust cloud on the horizon, and America's still waiting for that appeal.

Already in his mid-30s, Indiana was not exactly young when he started writing for the Voice. This might explain the range and nuance of his journeyman work as compared to that of so many emerging writers, which is usually long on voice and book-learnin' but short on genuine insight and artistry. Nevertheless, the preparation for this seminal work was not exactly what one might have expected, at least based on the evidence in the author's "first and last" memoir, I Can Give You Anything but Love (Rizzoli). The memoir revisits the first four decades of the author's life, from his childhood in New Hampshire to stints in San Francisco and Los Angeles during his 20s, ending with the harrowing personal apocalypse that catapulted him from California to New York: "I interpreted it as a sign," he writes. "Not a sign from God, who, unless he's truly the worst prick in the universe, doesn't exist. It was a sign from an enormous, disembodied imaginary fuck-you finger poking through a 'dense gray cloud of you'll never know.' "

Indiana's memoir comes with a warning, albeit on the last page, in which he informs readers that during the process of writing he "let go of any pretense of documentary reality." Indeed, Indiana told me (via email from Berlin, where he spent the early part of the summer before returning to his apartment in the East Village) he finds the memoir genre "disgusting," and after four years of writing had "more or less" turned his into a novel. To longtime readers, then, I Can Give You Anything but Love will fit right in with Indiana fictions like Horse Crazy and Do Everything in the Dark, which draw on people and events in Indiana's experience but transform them, in the manner of Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz or the Austrian playwright and novelist Thomas Bernhard, into "deformed, exaggerated versions of real life rather than depicting any documentary form of reality."

Caveat or cavil, though, this disclaimer doesn't make the book any less compelling. Born in 1950 in the small city of Derry, N.H., Indiana (ne Hoisington) reminds us that growing up gay in the Eisenhower-Kennedy-Johnson-Nixon years was, well, as shitty as you'd imagine. And though post-Summer of Love San Francisco was as filled with drugs as you'd expect, it wasn't all sweetness and light. "Our merry band dropped acid or mescaline or psilocybin and tripped off to the Nocturnal Dream Shows in North Beach," Indiana writes, but it all had "the muffled, overlit, queasy erotic gloom of Vertigo, with something in the grain of the daylight air a constant reminder that the drowsy dreamtime we occupied was sleepwalking to a bad end." That end came during a party at the house Indiana shared with friends named Ferd and Carol, when a member of the Hells Angels "threw me over his shoulder like a Visigoth looting a conquered village...and raped me for several hours while the escalating noise above us made it pointless to scream." The attack was so brutal that Indiana lay unconscious for two days. He "segued from depression to schizophrenia," hearing voices and talking to them, before managing to book himself a flight home and succumbing to "a complete mental breakdown." By the time he was 25 he was back on the West Coast, this time in L.A., where he was eventually reunited with Carol and Ferd. Still, he felt lost, or at any rate lacking direction. "I have no reliable idea who I am: I can be whatever somebody wants temporarily, if I glean a clear intuition of what it might be." It's a mind-set that works against permanent attachment, and Indiana picked up "a new person every night." Pleasure is not exactly the goal of these encounters. "The guys I pick up are impervious to emotional complications, intent on probing a fresh body, pushing beyond conventional sex, lab animals staging their own experiments. I do anything I'm asked that won't kill me. I'm averse to grunting leather ladies, but I'll go to a lot of the same places they do, taking the same risks. I prefer a Ray Davies -- or Bowie-looking type to fist me, whip me, whatever, over getting mauled by a human tank. It's not my usual thing: a no-fault fuck in the parking lot of time between last call and the morning reality principle, and a modicum of cordiality."

"A modicum of cordiality": It's hard to tell if that's Gary Indiana the writer talking, or Gary Hoisington the latter-day Lost Boy. Perhaps it's the tension between artifice and vulnerability that makes the passage so affecting, but I Can Give You Anything but Love is filled with lines like this. The rhythms are precise but not boxed in, the allusions cool, the metaphors so artful they're almost invisible, and if it's not Gary Hoisington's youth we're getting, it registers as an experience of youth nonetheless. What keeps it from being nostalgic in the manner of so many memoirs, let alone self-indulgent, is the memoir's second narrative, which follows Gary through his latest journey: to Cuba, in this case, where he has spent three or four or five months a year for the better part of a decade, including the four years it took him to write this book, a period that emerges with the immediacy of a diary.

"I travel because it takes my mind off of contingent circumstances that surround me where I live," Indiana says from Berlin. "Still, it's becoming more and more pointless to travel -- every place in the world is overrun with tourists, and everything looks more and more like America." One might mistake this tone for defeatism if it weren't coming from an American in a borrowed flat in Berlin, fresh from Dublin, where he celebrated Colm Toibin's birthday, and from Marbella, where he stayed at the "incredible finca" of a friend's mother. "I am too peculiar to figure importantly in anyone's life, including my own," Indiana says near the end of I Can Give You Anything but Love, which might be why he figures so large in the lives of his fans, whether they're the 50- and 60-year-olds who came of age with Indiana's work, or the Vice generation and re-emerging East Village art scene, which embraces him not as an elder statesman but as one of their own. "If younger people relate to my work, it's probably because I still wake up every day believing I'm 13," Indiana says. "I'm not a middle-class bore. I say a lot of things you aren't supposed to say. I get in trouble for it -- maybe a lot of people connect with that." I know I do.

I Can Give You Anything but Loveis available September 8.