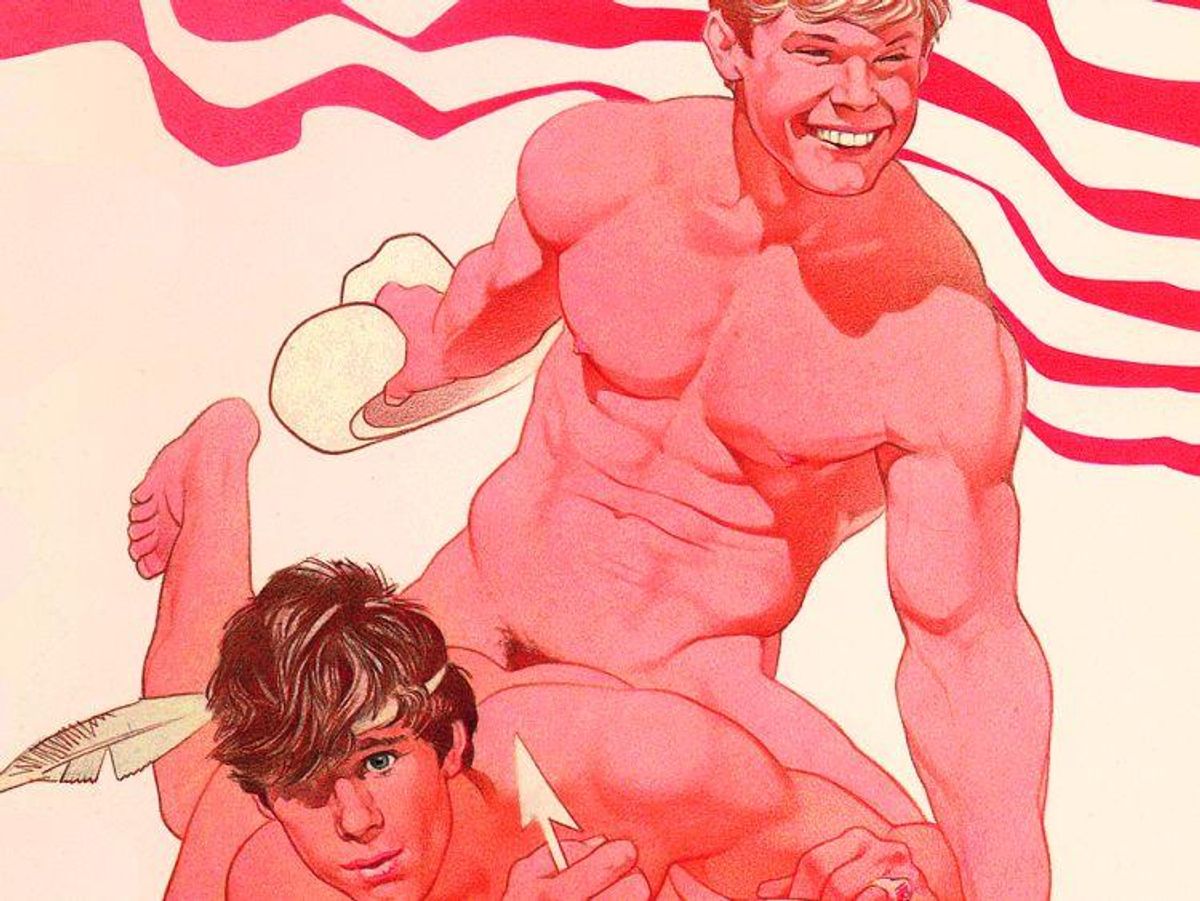

Harry Bush was a homosexual who drew male nudes throughout the 1970s and '80s for hardcore magazines but wanted nothing to do with gay people in particular. And although his work rarely deviates from the archetypal youths awakening to their primal urges at the very moment they reach physical perfection, the man drawing those images was a frail and aging hermit who kept an oxygen tank not far from his ever-present pack of cigarettes.

Bush has been described over the years as a talented bundle of contradictions barely covered by skin. Even as his work became more pointed and popular, Harry obsessed that if his fixation on the Boy Next Door ever got back to his relatives, they'd conspire to strip him of his government pension and lock him up in an old age home to die. Even so, and despite knowing that most of his colleagues worked under pseudonyms, Harry Bush signed everything he ever drew with his own name.

Bush died in 1994, of emphysema. He left a legacy of impossibly perfect teens dangling like ripe fruit in the half-light between adolescence and adulthood. But while the gay cognoscenti have long embraced many artists of the era, including Tom of Finland, The Hun, and Blade, much of Bush's work remains unknown outside a small circle of fervid collectors.

According to Bob Mainardi, who assembled the 2007 Harry Bush anthology Hard Boys(alongside partner Trent Dunphy), most of Bush's contemporaries were "leaning toward comic book cartoons. Much of their work was a parody of reality," he says. "Maybe Harry's work is more threatening because it's visually more realistic. People would look at it and think that these drawings were taken from life."

Anyone personally acquainted with Bush knew he was in no shape to prowl the streets trolling for models on the cusp of manhood. Mainardi met the artist in his declining years, after they were introduced through a mutual friend, "Blade" artist Neel Bate. After striking up a correspondence with Bush, both Dunphy and Mainardi visited San Juan Capistrano, where Harry worked in the privacy of his condo.

"It took a while to earn his trust," Mainardi muses, "because Harry felt he'd been burned so much in the past, by people who either didn't return his originals or didn't reproduce them to his specifications. In his mind, there were lot of people who wronged him, so sooner or later he seemed to have a falling out with everyone."

Being both a perfectionist and curmudgeon earned Bush a reputation as difficult to work with, and as word circulated, it undoubtedly cost him both fame and fortune. Touko Laaksonen -- better known as Tom of Finland -- was well promoted, says Minardi. "Especially by Bob Mizer, a publisher who also promoted Harry for a while, until they had a disagreement about something or other that ended their relationship. Tom of Finland went on to come to America and get involved with a model of his named Durk Dehner, who promoted Tom and started a foundation dedicated to him and got him published elsewhere and all kinds of recognition. And The Hun was online very early and marketed himself very actively on his own; he'd go places and sell his art there. Harry would never have done that."

No matter, Mainardi says. Bush's craft and dexterity are unassailable. "First of all, I thinkHarry's art stands out because he was a brilliant technician; his ink is so meticulously composed. He dismissed everything he did in oils and watercolors, but even so, his technique is just far above everyone else's, including Tom of Finland. Harry's art may not be as cartoonish, but there's a healthy dose of wit at work. It's one of the things that makes him such a conundrum; that he was basically unhappy and so alone, but his work is full of joy."

For some, thumbing through a Tom of Finland catalogue is no more provocative than skimming through an issue of Superman, because the figures do not capture perfection, they exaggerate every possibility -- similar to the expanse between a Village People video and soft-core porn. Several years before the book was published, Mainardi recalls hearing from the director of The Drawing Center in New York who'd heard about Bush's work.

"She came out to San Francisco and looked through the entire collection, and she loved it. But she said she couldn't show any of it. She said, 'People would be outraged.' "

Mainardi and Dunphy hoped Hard Boys would provide the kind of introduction to HarryBush that the artist could never muster. "My partner and I have known a lot of gay artists," Mainardi says, "and to one degree or another they all have creative and emotional conflicts. Oftentimes they're trying to work something out. Just like van Gogh created a night sky with swirling stars all around, they they're trying to capture something that may only exist in their mind's eye -- something the artist would like to be true, but isn't real."

If Bush's drawings continue to captivate succeeding generations, Mainardi believes it's because they're about "living without shame, especially when you're young, which I still think is difficult. It's still a tough time growing up and deciding how to come out or whether to come out at all."

And what about Harry? How would the misanthropic artist have assessed Hard Boys? "I like to think he'd have liked it," Mainardi says cautiously. "We did print it on the best paper we could afford and took as much care with the images as possible. So he'd have either loved it -- or he never would have spoken to me again."

Hard Boys is currently available.