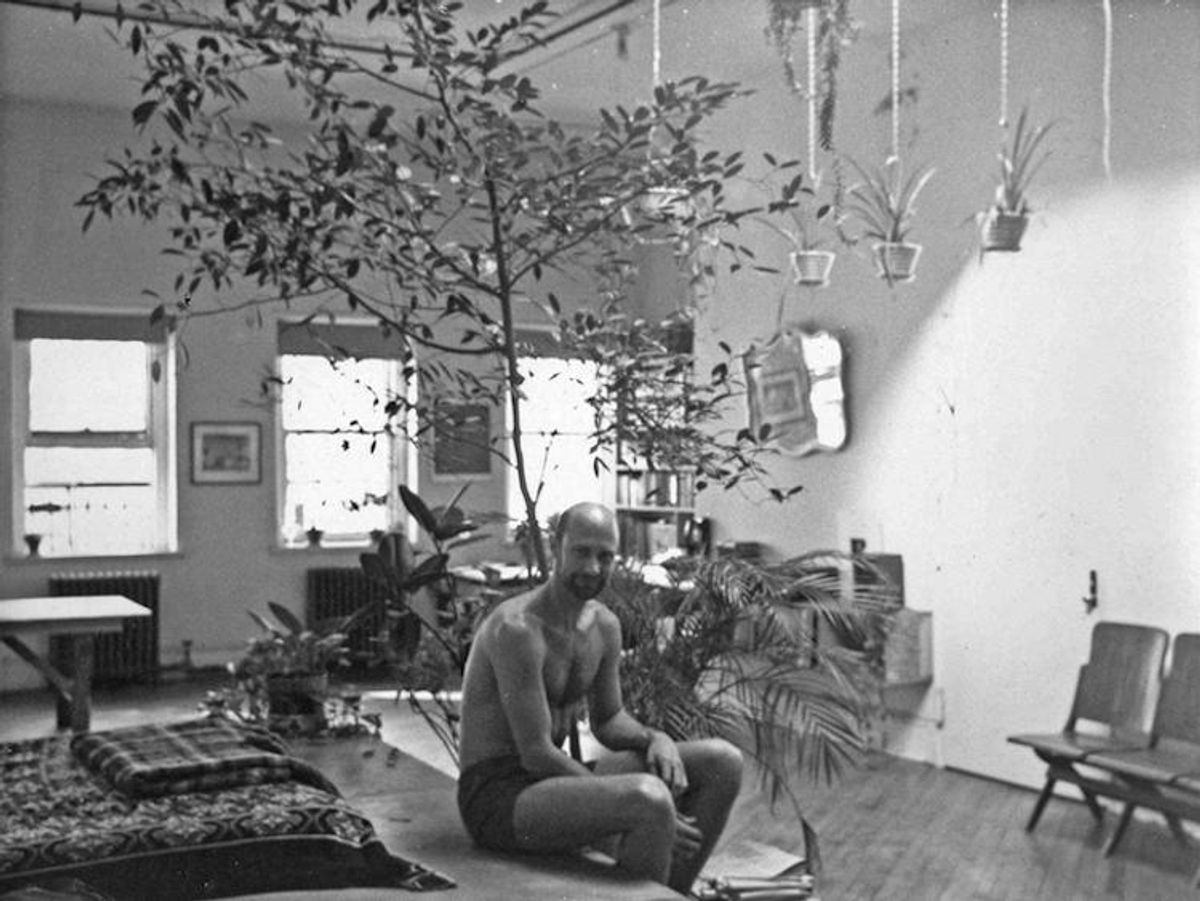

Crimp in his Chambers Street loft, c. 1975. Photographer unknown.

Douglas Crimp, one of America's foremost art critics, marries the personal with the critical in his new memoir, Before Pictures. The book explores life in 1960s and '70s New York as the city's radical art scene merged with a thriving gay community.

Living between these two spheres gave Crimp a distinct New York queerness. "I would have to learn how and where to be queer all over again," Crimp tells Out, "since being queer is a matter of a world you can inhabit, not something you simply are."

Crimp details many of the encounters he has had with iconic artists like Andy Warhol and Cindy Sherman, while charting his impressive career as a Guggenheim curatorial assistant and critic for Art News. But Before Pictures is also punctuated with more intimate stories, from Crimp's rendezvous at the disco, to late nights at the bathhouse, to sexual liaisons with some of New York's most celebrated gay men.

Out: Before Pictures is part autobiography and part cultural criticism. Why did you take this approach?

Douglas Crimp: My idea to write a book about New York in the 1970s originated from my ACT UP days. Many of my activist friends were too young to have experienced gay life in the decade before AIDS struck, and they urged me to write about it. We all wanted to counteract the narrative that was being pushed: that the 1970s represented gay men's immaturity and led inevitably to AIDS, which in turn made us grow up and become responsible citizens. My intention was never to write simply about myself. I always thought of Before Pictures as a generic hybrid, one that would juxtapose the two New York worlds I was part of in the 1970s--the art world and the gay world.

You grew up in Idaho in the 1960s before moving to New Orleans and then later to New York. What kind of culture shock did you experience moving to these big cities? As a young gay man, was it liberating to be living in cities with burgeoning gay communities?

The culture shock I felt arriving in New Orleans was total, including even the weather. New Orleans had an active port with ships from all over the world along the river in the French Quarter. The first bars I went to were sailors' bars. They were seedy and kind of rough, with a wonderful mixture of sailors, prostitutes, drag queens, bohemians, and some adventurous students. Eventually I went to gay bars too, and came to feel very comfortable in them. They were very different from the bars we know now. What the clientele shared was our pariah status. Arriving in New York was disorienting for me. Eventually I found my way to the backroom at Max's Kansas City, where the Warhol crowd hung out. That was a fabulously queer scene.

Douglas Crimp in his office at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, c. 1970. Photographer unknown.

Looking back, how has the New York art world changed from the 1960s and 1970s to the New York art world of today?

The change is so enormous as to be almost unbelievable. Size and money are the main differences. The art world of the 1960s and '70s was small--it seemed like everyone knew everyone else--and the various cultural worlds overlapped much more than they do now. Artists formed the main audience for dancers, poets, and musicians and vice versa. No one had much money or expected to make any.

Of course, there was an art market, but it was small potatoes compared to now. One chapter of the book is about the Agnes Martin show I curated for the Visual Arts Gallery in 1971. MoMA and the Whitney Museum lent paintings to be shown in the scruffy little gallery at the School of Visual Arts, which had no climate control and little security. The paintings weren't insured for all that much. Now those paintings are worth tens of millions of dollars. New York wasn't an expensive city then. You could rent a 1,000-square-foot loft in Tribeca for $100 a month.

Do you think there was an important relationship between New York gay life and the New York art world during this period?

That's the subject of my book. Negotiating those two worlds was not always easy in the '70s. My art and gay worlds were fairly separate--with some overlaps, of course. It was rare for people older than me to be open about their homosexuality. Warhol was unusual in that respect, and that's why I was attracted to the scene at Max's. But I write in the introduction to the book about the spatial division at Max's as a metaphor for my experience of the segregation of the two scenes. The straight artists hung out in the front room, the queers in the back. I had to walk by my artist friends to get to where I wanted to be. Not stopping to join the artists was a statement about which scene I preferred.

[Robert] Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith lived in the Chelsea Hotel then, and I lived across the street, and we'd often walk over to Max's at the same time. I knew Robert slightly and later often saw him at the Keller bar. I also knew his lover and supporter Sam Wagstaff, who lent two paintings to my Martin show. Wagstaff was a patrician museum director whom everyone knew was gay, but nobody talked about it. The same was true of Ellsworth Kelly, with whom I had a very brief liaison.

In Before Pictures, you explore your experiences at discos and gay clubs, as well as your sexual liaisons with some well-known men at the time. What was invigorating about gay life in the city at this time? What was the sense of community?

Everything about it was invigorating. Everything was exploding: radical queer politics, new community organizations, gay publications and bookstores, bars with backrooms and bathhouses with orgy rooms, dance clubs and sex clubs. Sex! The Anvil. The Mineshaft. The trucks. The piers. I especially loved and miss outdoors sex--besides the trucks and piers, the Ramble in Central Park, the Tuilleries in Paris, the Villa Borghese Gardens in Rome. Gay life is so privatized now--in the 1970s we occupied public space.

Everywhere we went we cruised--in the streets day and night and into the early morning, in the subways. I once met a guy on the No. 1 train who had keys to the locked men's rooms in the subway stations, and that's where he took me for sex. Now it seems like no one cruises except by looking into their iPhones. You could be sitting right across from the hottest guy in the world and not even notice. We cheerfully asserted ourselves, flaunted it I guess you could say, and we were every inventive. The word that probably best characterizes the gay scene then is "experimental." The sexual liberation ethos was "don't knock it until you've tried it." A great sense of community grew out of that shared ethos.

Before Pictures is available here.

Nathan Smith is an arts and culture writer. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and Forbes. Nathan tweets at @nathansmithr.