In 1946, Scotty Bowers, then 23, had returned from World War II and landed a job as a pump jockey at a Richfield gas station on Hollywood Boulevard and Van Ness Avenue, in Los Angeles. Like much of the U.S. at the time, Southern California was flooded with young men returning from war: penniless, listless, on the make for work or wives or both, with little to fill their days other than hanging around with old military buddies.

Bowers worked the night shift and, just a few days in, the actor Walter Pidgeon propositioned him while he was filling his tank. Bowers got in the car and went home with him, where Pidgeon performed oral sex on him and gave Bowers 20 bucks.

Bowers had been hustling since he was a child -- "on the ball," he calls it. At 11, when he moved with his mother to Chicago from a small farm in rural Illinois, he became involved with a Catholic priest who lived across the street, he says, getting a dollar every time he performed a sexual favor.

"As a little kid, if someone was interested in me, I picked up on it and I was available, whereas a lot of kids would call the law," he says. "Pretty soon, I was having sex with every Catholic priest in Chicago."

He also sold newspapers and worked as a shoeshine boy. One day, when the 11-year-old Bowers was selling the Chicago Tribune for 10 cents a piece, someone asked if he had any condoms to sell.

"The next day, I went to the Chicago River and got a long net with a pole, and I went fishing for rubbers. They came out of the sewer, and I'd scoop them up, wash them off, and hang them on the fucking line to dry. And that's how I got into the rubber business. One Sunday morning, I had 150 goddamn rubbers hanging on a fishing line drying off," he says. "Anything anyone wanted, I found a way to get it."

At the gas station, Bowers noticed male customers were often eyeing the handsome young vets, sometimes saying things like, "I'd sure like to take that one out to dinner." Bowers thought to himself, Why don't you skip the fucking dinner and just give him 20 bucks to suck his dick?

It took little arm-twisting, Bowers says, to get the tricks on board. They were broke and bored, and had little to lose, and soon, as Bowers writes in his book, Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars, "My gas station became the focal point for everyone looking for a trick. It became the crossroads of the city's sexual underbelly.... Whenever anyone was on the prowl for sex, my gas station was the place to head."

He drilled a hole in the washroom wall and charged men $5 to watch guys urinate, or masturbate. An unused trailer, which a neighbor paid to park on the lot, became a place for on-site sex, and a two-story brick motel across the street, where a "sweet, fat old queen" was the night manager, offered hourly rates to Bowers and his boys.

Bowers says people had been hounding him for years to write a book about his days as Hollywood's gay Heidi Fleiss. "Finally, I thought, what the hell. Years ago, I would never have written a book with living people, because they were friends. Good, close friends," he tells me, seated on the back deck of his home, a small bungalow perched high on a hillside in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. "Everyone is dead now."

Full Service, published by Grove Press in 2012, became a New York Times best seller, and is currently being adapted into a movie by Matt Tyrnauer, director of Valentino: The Last Emperor. Bowers wrote his book in collaboration with Lionel Friedberg, a writer and filmmaker living in Los Angeles who met Bowers at a dinner party in Beverly Hills. According to Bowers, the two were guests at the party. According to Friedberg, Bowers was the hired bartender.

The book is an upbeat romp through decades of the sex trade during Hollywood's golden years, with Bowers at the center. He claims to have had a 50-year friendship with Katharine Hepburn, adding that he set her up with more than 150 women. And he says he was a regular in Cary Grant's bed, at a time when Grant was married to Barbara Hutton. Among the other big names Bowers says he got to know, sexually or by arranging sexual liaisons are Gore Vidal, Cole Porter, Rock Hudson, director George Cukor, Spencer Tracy, Errol Flynn, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, each with unique sexual tastes, mostly gay or bisexual, that Bowers was consistently able to satisfy.

"Cole Porter's passion was oral sex," Bowers writes. "He could easily suck off 20 guys, one after another. And he always swallowed."

Tennessee Williams, says Bowers, wrote a short story about him. "He made me look like a mad queen flying over Hollywood Boulevard, leading around all the other queens," Bowers says, claiming he made Williams tear the story up. "Tennessee actually cried when I asked him to do that."

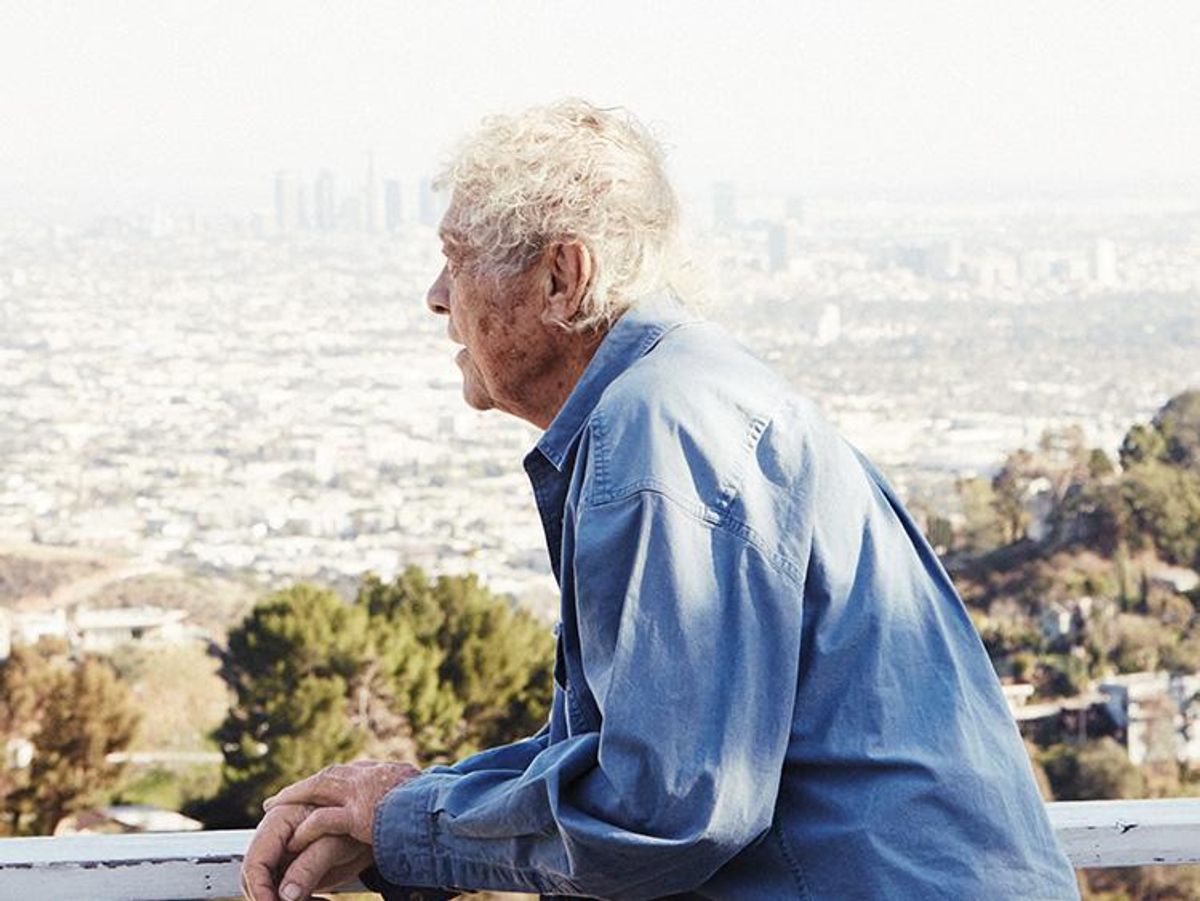

Even at 92, Bowers is an impish old man with dazzling blue eyes and a wash of pearly hair. He likes blue jeans and denim shirts, reminiscent of the uniform he wore at the gas station. He's personable and funny, and one wants to believe him. Maybe everything he says is completely true. Or maybe not. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and Bowers has none. There are no photos of Bowers with his celebrity friends, no personal letters that can be traced to them, not even a photo of the trailer parked behind the gas station. Although in the memoir he alludes to a little black book of names and phone numbers, he now says that never existed. He did not keep a personal journal or diary. And, of course, everyone is dead. Everyone except for a woman named Barbara, whom, he claims, he set up with Hepburn when Hepburn was in her 40s and Barbara was 17. He says the two maintained a relationship for the rest of Hepburn's life, but no one investigating Bowers's story has yet been able to verify if Barbara even exists.

"Now [Barbara is] married to a guy with a lot of money, and he doesn't know anything. From time to time, she still gets in touch with me, but I don't call her because of her husband," Bowers says.

The other problem relates to gut instincts. The world Bowers creates comes off as almost too decadent, too Babylonian, too larger-than-life to be entirely true. For all the talk of her tomboyish ways, dozens of biographies were written about Katharine Hepburn with no suggestion she was gay. At least not until 2006, with William J. Mann's book Kate: The Woman Who Was Hepburn, which rests a great part of its narrative on that possibility. Mann's source for this information? Scotty Bowers. Then there are the 150 women allegedly paid to have sex with Hepburn. Oddly, none has come forward with her own tell-all.

According to Friedberg, Grove Press lawyered up when it signed the book and the text is libel-proof, namely because no one in it is still alive to sue. Friedberg says he never doubted Bowers's stories, namely because they were so consistent, down to the smallest details.

"It was clear that everything tied in with people he said he knew, songs that were being made at the time. It became very clear that none of this was fabricated. I went around town and asked, and everyone said, 'Oh, yes, I remember Scotty telling me that story," Friedberg recalls.

"I would not have put anything on paper if I wasn't absolutely, 100% certain it was true," Friedberg says. After the manuscript for Full Service was completed, he gave it to Gore Vidal, a lifetime friend of Bowers. "Gore read it and, sitting at his dining room table here in L.A., said, 'Everything you have written in this book is 100% true, and I can vouch for that.'"

Vidal also provided a blurb for the book jacket. In 2010, however, Vidal begun suffering the effects of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, a brain disorder caused by alcoholism (he was officially diagnosed in 2012). The symptoms include severe memory loss, and Vidal died two years later.

Other than that, there's no one to corroborate Bowers's story besides Bowers. Yet Bowers does not seem completely full of shit. In the introduction to his book, he says he was not motivated by money but wished just to get this part of Hollywood history down on record. "I've been reading about this case, and I think skepticism is a good place to start," says Lawrence Patihis, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Mississippi, who studies memory, particularly autobiographical memory. "When people get older, they get less good at distinguishing whether a memory was imagined or whether it really happened."

Being able to recount a story verbatim, in exquisite detail, is not necessarily a sign of a true or a false memory, Patihis argues. "In order to get that consistency, you just have to replay the memory many, many times -- go over it many times in your own mind. You can have that consistency in your memory even with false memories."

Michael Cunningham, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Hours and, most recently, A Wild Swan and Other Tales, is more sanguine. "We know Cary Grant was gay," he points out. "Look at all those pictures of him at breakfast with Randolph Scott. But queer history is full of secrets. And there's no proof about people who are no longer here to tell the tale, and they range from Abraham Lincoln to Marlon Brando. I think our relationship to our own queer history should be what we decide it is."

Bowers takes me into his Laurel Canyon house to show me around. His wife, Lois, is nestled in the far-left cushion of the sofa, where she's peeking over her glasses at the television; a rerun of Keeping Up With the Kardashians roars through the room.

Next to the sofa are several cans of paint, a stack of flashlights, a bundle of unused Priority Mail envelopes from the post office, a bag of wine bottle corks, a pile of Beanie Babies, and a stack of telephone books. To the left, the dining room table is covered in papers; old mail; documents heaped three feet high, nearly reaching the chandelier; and an assortment of Tiffany-glass lamps and decorative blue vases. There is a narrow path meandering through the living room toward the kitchen. On the right, hundreds of magazines and tabloids are piled atop the coffee table in the shape of a desert mesa. On the left side, a mound of umbrellas, picture frames, Christmas ornaments, alarm clocks, and other bric-a-brac frames the pathway. In the kitchen, a towering jumble of aluminum cans balances on a drying rack. Bowers produces one of his favorite possessions, a photo of him and Lois taken 30 years ago. It's a snapshot blown up to portrait size. They're sitting at a table in a restaurant, and Bowers looks more or less the same. Lois's right hand is delicately touching the handle of a teacup; in her left hand she holds a cigarette. They are laughing. She's looking at the camera; he's looking at her. His hand is touching her hand. He produces another photo, taken in 1955: Bowers and four other guys sitting in a new Thunderbird.

"These were all guys from the gas station," Bowers says. "They're all dead now." He glances at his wife, who is unblinking in the same position, glaring at the TV, and lowers his voice to a whisper. "This guy had a prick like this," he says holding his hands about 12 inches apart.

We step back out onto the narrow deck. It feels poised to tumble down the hillside at any moment into the Los Angeles basin, where the quiet city stretches as far as the eye can see. The tidy skyscrapers of downtown huddle at the center of the view, veiled in a thin, brown layer of smog that has obscured the snow-capped mountains to the east. A pair of red-tailed hawks hover a few yards out.

"Those goddamn hawks," Bowers says, squinting through the sunlight, licking his lips, his right hand bobbing rhythmically. "They never flap their wings. They just ride on the air."

Bowers resists commenting on anything other than what is immediately in front of him. He recounts the stories of his life in meticulous, scripted detail. But when I prod him for something deeper-to philosophize-there's a pause, as though he is searching for the bigger picture, and he comes up short.

I ask: What's been the meaning of his life?

Bowers stares at the golden sunlight on the concrete, his right hand still dancing. Licking his lips again, he rises and shuffles over to a corner, empties a bucket of stagnant rainwater onto the patio, and shuffles back to his seat.

"Back at Iwo Jima, in those days, when you were wounded, you'd head back toward the beach by yourself. And then you'd bleed yourself out to death on the beach, alone on that black sand," he says. "And when you're dead, you're dead, baby. I've seen too many fucking dead people."

We like to believe the worst, most tawdry tales of Hollywood, that actors have decadent, scandalous lives, but Cunningham has a different take on his time in the homes of the famous. "They're actually more guarded than most people," he says. "You go to all those Hollywood parties, and everybody is so nervous. Everybody knows, somewhere at the party, there's some producer who might or might not hire them someday. People stay sober. There's no funny business."

Bowers may be telling the truth -- or it may just be the truth we want. Does it matter?

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of OUT. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.