Art & Books

Blood Lines: How Catherine Opie Made Her Mark

Before she shot surfers, Opie's work reveled in bondage and needles.

March 24 2016 5:19 AM EST

March 24 2016 12:24 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Before she shot surfers, Opie's work reveled in bondage and needles.

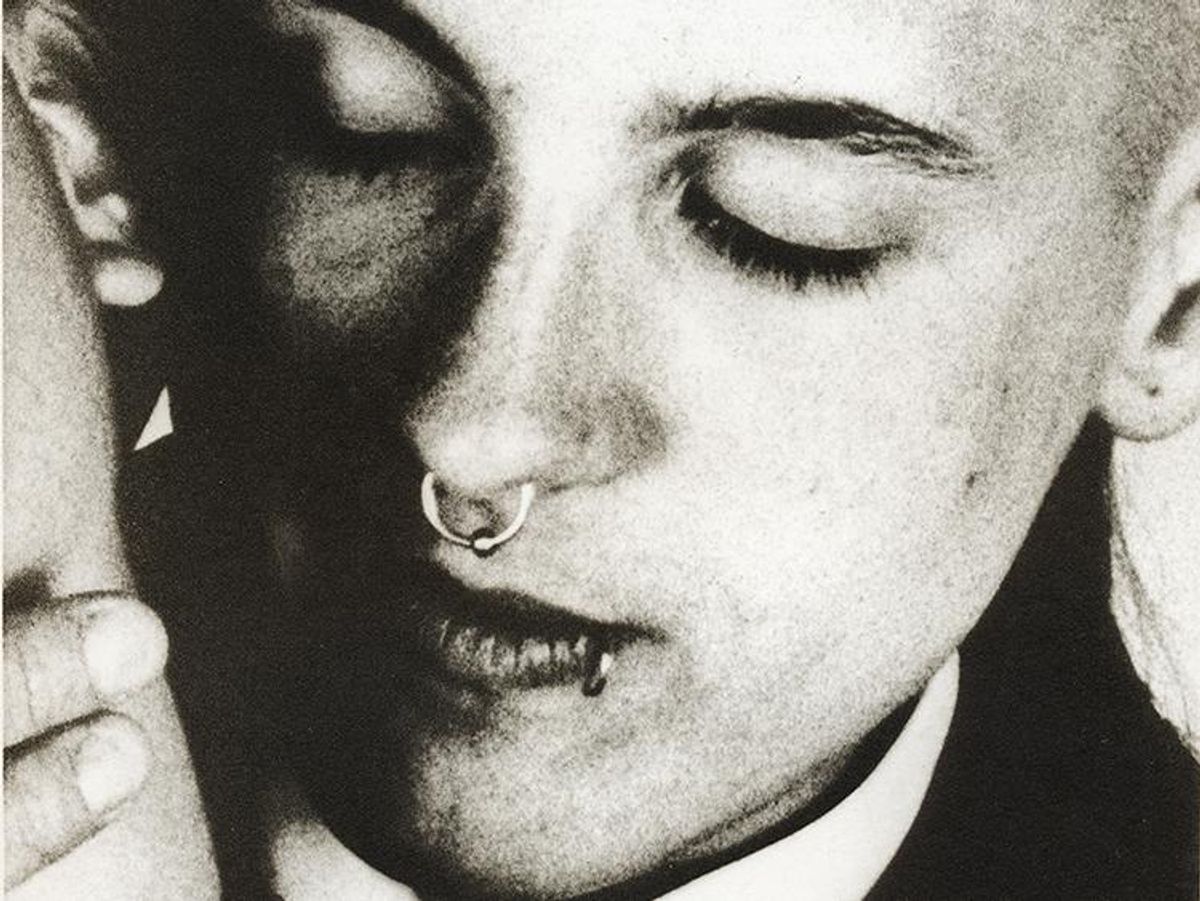

Untitled, 1999

As a young photographer in 1980s San Francisco, Catherine Opie became fascinated by the "X Portfolio," Robert Mapplethorpe's visceral portraits of bondage and sadomasochism. After making friends with a gallery owner who represented Mapplethorpe, Opie, a member of the S&M community, visited time after time to privately view the images.

"I took lots of photographs throughout the '80s, especially black-and-white photographs, and they were never really good enough. They just looked like Mapplethorpe photographs," Opie says on a recent afternoon at her studio in the West Adams district of Los Angeles, the barn door of which is framed by a pair of orange trees, flung open, with roosters crowing in the background.

In 1999, while fiddling around in the darkroom with some of those photographs, she selected detailed moments of larger photographs. The result, her "O Portfolio," has a different sort of intimacy than Mapplethorpe's sharp, full-scale scenes: Hers are grainy, tender fragments of bondage, blood, and needles.

Now, for the first time in L.A., Opie's "O Portfolio" is being displayed in its entirety at LACMA. Through September 5, it will complement Mapplethorpe's "X," on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum as part of the exhibition, "Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium," co-organized by the two museums.

" 'O' is the Story of O," Opie says, referring to the 1950s erotic novel. "It's my last name, Opie, and it's vaginal. And then it's X and O, like tic-tac-toe, so it's a game with Mapplethorpe."

Also this year, in Los Angeles, Opie is working on a commission for the new federal courthouse downtown. It's a series of six photographs. Each panel is 8 by 16 feet, and collectively they depict a single image of Yosemite Falls from the top peak to the water below. The photographs will be displayed on six stories, with the bottom two floors capturing the reflection of the falls in the river.

That's my scale of justice," Opie says. "People who go into a federal courthouse will often lose their life's liberty. What is iconic in California? Yosemite Falls. How do I make something work on a metaphorical level in relationship to that iconic weight?"

Opie rocketed to fame in the art world in 1994 with a single photograph. She carved the word pervert into her chest and took a self-portrait. It was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

"I'm a fan of blood," Opie says. "The permission to play with blood in the '80s and '90s was very much political in relation to the AIDS crisis in our community. Blood became the substance everyone was afraid of."

Opie says she's mesmerized by the specificity of community, which she sees as something closer to landscape.

"When you drive through California and you're heading up to the mountains, you understand that landscape is innately your experience of what the drive is going to be," she says. "It's the same thing with identification in our community. If you're walking through the Castro in the early '80s with a leather jacket and some cock rings on your snap lapel, you could identify as queer. I look at it as signifiers and identification in the same way we map out landscape."

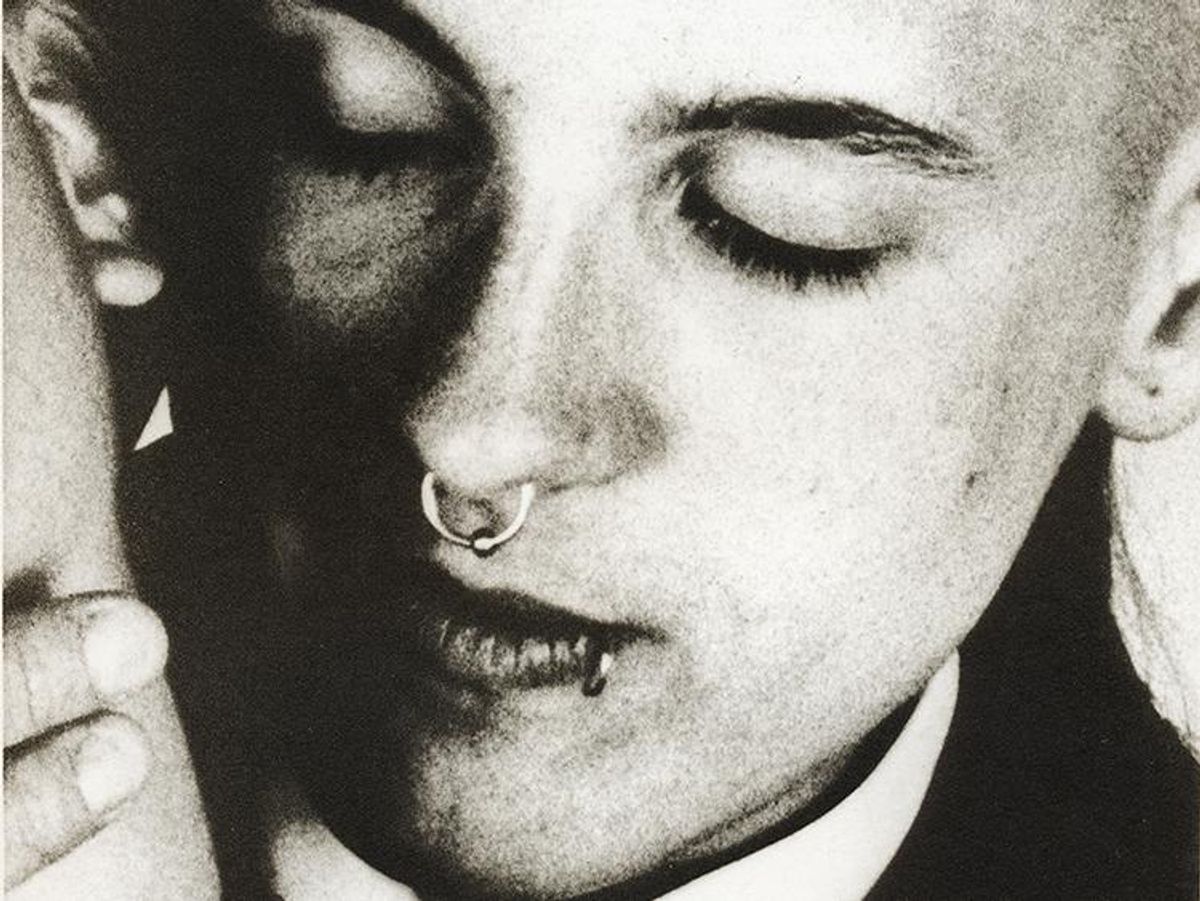

Untitled #1 (Surfers), 2003

That idea, in the early 2000s, led to two more of Opie's most celebrated works. She was grappling with the question of how to assess the American landscape through photographs. One August, she was visiting her lover's family in Louisiana.

"It seemed to me, let's talk about it from the site of a high school football field, because wherever you go in this country, there are going to be lights on, a high school football game during the fall. It is utterly a part of American identity."

Opie asked if she could take portraits of her nephew's high school football team at practice.

"I began to think about their vulnerability in a way I never thought about with high school football players before, and part of that is being at war. So many of these young men are going to go off to war, and some of the ones I photographed did go off to war and they did die," she says. "In the same way I was supporting my community in the '90s, and bearing witness to AIDS decimating that community, all of a sudden I realized somebody like a high school football player is vulnerable as well in so many different ways. But as a culture, we load the politics of masculinity and power and all these things onto them."

A few years earlier, she shot another series of portraits of young men, this time surfers, but found her subjects were almost too pretty for portraiture. The resulting images were distant and hushed specks of flesh floating on the surface of an abyss, portrayals of a community she describes as temporary, almost nomadic.

"The iconic image of the surfer is the action shot. Just like the action shot of the football player," she says. "But if we take it as landscape, then how do we think of it in a different way? Can it be meditative? Can we acknowledge space in a different way?"

When Ansel Adams photographed the American West and Yosemite, he received complaints that there were no people in his photographs. In Opie's work, in a different sense and in a time preoccupied with branding the individual, that could be the appeal. How we think of ourselves would be radically different if more people looked past each pretty surfer, and saw the ocean.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of OUT. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.