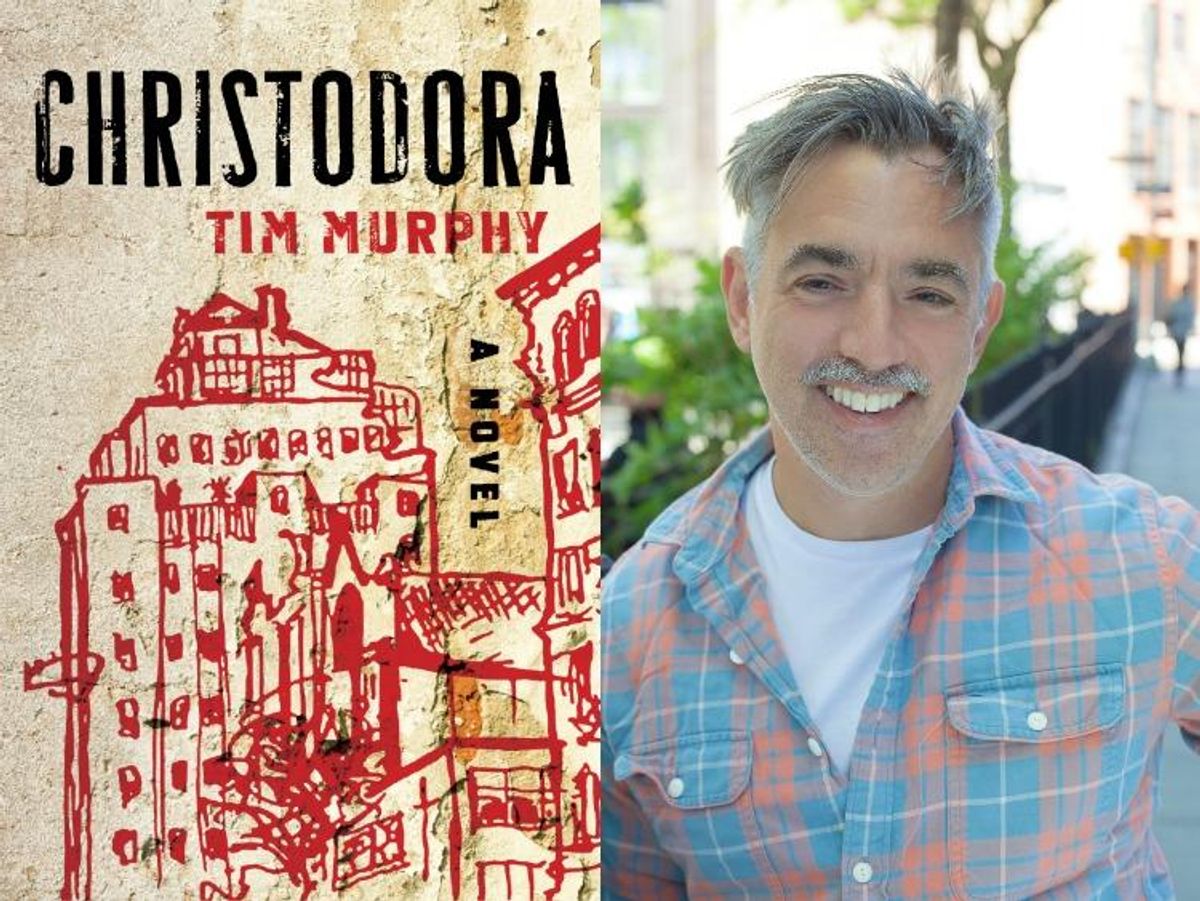

In Tim Murphy's debut novel, Christodora, he retraces four incredible decades of gay history in New York City, starting with the dawn of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and leading up to today.

Set in the iconic Christodora Building in Manhattan's East Village, Murphy's novel explores the intersecting and often complicated lives the building's residents--both straight and queer alike--across many tumultuous years. Murphy masterfully unpacks issues of family, identity, and home across the kaleidoscopic-life stories of his characters.

Murphy demonstrates that buildings like the Christodora are central cultural landmarks of the city, carrying not only enormous personal history for members of the LGBT community, but also representing a time when New York was untouched by mass gentrification.

Out: What was it about the Christodora Building that made you center your book around it?

Tim Murphy: The Christodora has always been vaguely on my radar. Somewhere about halfway through writing the book someone triggered my memory about the anti-yuppie storming of the Christodora lobby in 1988 after it went condo. The building's history reflects the city's history of the past 40 years or so--the same as the span of the novel--from utter dereliction to gentrification and extreme wealth. Plus, I love the name. Someone told me the other night that Madonna had a place there in the late eighties, lthough I can find no such documentation. Same for Cher. Iggy Pop definitely lived there.

Do you think New Yorkers have a unique relationship to their buildings that perhaps people in other big cities don't experience?

In New York, a big apartment building is like a little village unto itself, with the doorman--if there is one--or the super being like the mayor or the editor of the local paper. I like how relationships in these buildings form slowly and kind of elliptically because only in New York could you live alongside someone for years and barely know them. But relationships do form over time. I have a friend still in the building where I lived from 1993 to 2001 and she tells me what's going on with people in there. New York apartment buildings are like big filing cabinets that contain lives.

In Christodora, you explore the ubiquity of drug use among gay men across the decades. How do you think drugs have shaped gay culture?

Drugs have enabled or enhanced a lot of sex and revelry for gay men, probably maybe even more so in earlier years, in the midst of an atmosphere of shame and stigma and personal repression. Like sex, drugs can be great, but they can also be addictive and end up taking over your life. There is quite a body of research now showing a link between trauma and drug addiction, and I think many gay men who lived through the worst of the AIDS years in the U.S.--whether HIV negative or positive--later found drugs--particularly crystal meth--a way of numbing the trauma and the loss.

In the novel, I was certainly trying to illustrate this through the character of Hector. For me, drugs were a huge source of sexual and psychological escape until they ruined my life. But now I'm in recovery. I'm weirdly grateful for the experience because I think it forced a kind of reckoning in my life that ultimately brought me to a different place, a different way of processing life and feelings.

During the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s, many gay men felt like they had become second-class citizens in America, no longer feeling "at home." How do your characters form their own sense of home? Is it at the Christodora?

I would say that big cities like NYC and San Francisco were the only places where gay men with HIV/AIDS did feel at home at that time, because there was a large gay caretaking and an activist communities. In the book, I think that the characters who feel alienated from their own workplaces or families find a surrogate family in the activist movement of queer women and men who made up ACT UP and Queer Nation. That was a terrifying and stressful time for many gay people, especially those who were sick, but there was also a tremendous sense of mission, solidarity, family and even, sometimes, of fun being part of those collectives.

You map out different time periods from recent gay history. Was it difficulty writing multiple intertwining histories?

It wasn't really difficult because I started the book envisioning it as a collection of loosely linked stories. But it was an extremely emotional book for me to write. I actually cried writing certain chapters and felt a bizarre closeness with almost all the characters because they were all based in part on some very intense strand of my life, whether it was severe depression when I was in my twenties or addiction or the painful, slow, halting process of recovery. But it was also a nostalgic book for me to write because a big chunk of it is set in the 1990s, so I was thinking a lot about being young and crazy in New York and the good times with friends I had then. The book is like a secret set of valentines to so many people I have known, and some of them I have known only briefly, or not that well.

Publisher's Weekly compared your novel to Tom Wolfe's Bonfire of the Vanities. Christodora really is a "big New York novel"--only concerned with gay life from the 1980s to now. But did you ever actually set out to write a "big New York novel"?

I was thrilled about that comparison. I have always been drawn to these big social novels about cities teeming with characters. New Yorkers are very solipsistic about New York but I think that's okay because we basically live in the most global, fascinating and driven city in the world. I mean, this is where people come when they want something better or more interesting than where they're from. How can a place like that ever get boring if you are really keeping your eyes open as a writer?

Purchase Tim Murphy's Christodora here.

Nathan Smith is an arts and culture writer. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and Forbes. Nathan tweets at @nathansmithr.