"The capacity of resistance, as a teenager, fascinates me," says Camille Rouzaud, whose raw, intimate work spotlights subjects that embody a natural sense of liberation from oppressive social restraints. Having grown up in public housing, the queer New York-based visual artist now shoots with strong empathy, seeing eye-to-eye with the diverse experiences of those behind her lens. Their courage is unconcious, echoing a childhood she recalls being a "period of repression, rebellion, and a constant search for total freedom."

Related | Gallery: Camille Rouzaud's Raw, Rebellious Photography

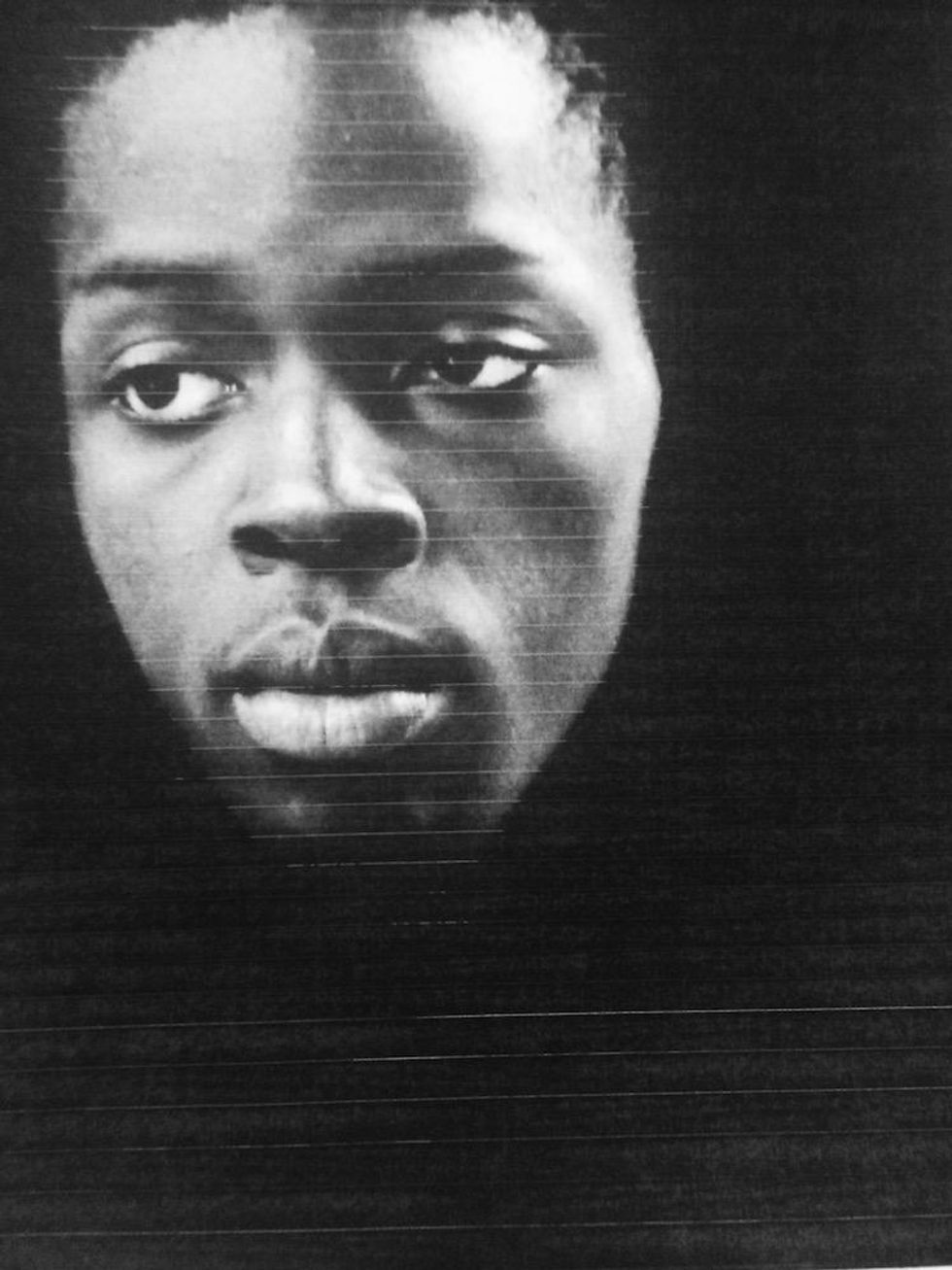

Rouzaud's body of work primarily focuses on boys, which is a mirror to the artist's own gender fluidity. She relates to boys' attitude, capturing their riotous energy through gritty, lo-fi images, many of which she distorts in post-production. Sometimes they're tightly cropped in, cutting off the face and focusing only on their chest, their chin, their rib cage. Other times she tears her images apart, reveling in the jagged edges to combine them with another photograph. Much like she's learned to appreciate "the movement of life," Rouzaud's final product is a study in spontaneity.

We recently caught up with Rouzaud to discuss her background, traveling from France to Puerto Rico, and how these early life memories have informed the poetic photography she creates today.

OUT: How has your upbringing influenced the work you do today?

Camille Rouzaud: I grew up in a very small village in the south of France, and then at age 10 we moved to a nearby city and lived in public housing. Being indoors in the village was hard. I spent most of my time outdoors with friends, running in the fields, playing with bows and arrows, driving motocross, jumping into the river with bikes. Everything was a game.

In public housing the games were much more serious--hard, desperate, violent, but also rich. The diversity of people I got to meet, the new games we played like occupying old train cars or biking four per moto. We were pretty much growing up on our own, and it was wild and fun and freeing. I believe that my childhood influenced my work the most. It was a period of repression, rebellion, and a constant search for total freedom.

As you moved into adulthood, how did your environment shift?

At age 20 I moved to Barcelona, Spain, and for the first time I was in a place that was more socially openminded. It gave me the freedom I had always craved and allowed me to be a little more myself. But the inspiration [for my art] came while I was living in Puerto Rico. It's one of my favorite places on Earth. During this time on the island, I was pretty lost and at the same time my creativity started to come out very strongly without my acknowledgment. It just sort of happened. I finally got led to New York where I currently live--the city where you can be your absolute self.

Why did you first get involved with photography and how has that intention changed across the years?

I saw my first photography exhibition at age 15, and it was there that I asked my mom if she could give me a film camera. I can't really explain why. I just wanted to embrace the world that I had no hold on, and I think photography was a good way for me to try to keep details of a more interesting world that was about to be lived.

That's an analyzation I have now. I did it instinctively, as were the subjects I developed at first. It was instinctive and now I know why it has a strong link to me. Because I understand myself better now, I am able to transform my work and go beyond just photography. But this is still a work in process, of course.

What do you consider a good image?

I think a good image depends on its ability to create energies and emotions--something brutal, sometimes.

Your work doesn't start and end with taking a picture. What's your process for post-production?

Distorting them, cropping, printing, collage, scanning... all kinds of transformations are my very favorite part. When I already have the pictures, and I know I have some valuable material, being by myself with a room filled with prints, cutters, black markers... that's the greatest moment for me. I'm mostly post production and absolutely not pre-prod. It's a leitmotiv in my life. If I plan something, most of the time it never happens that way. That's why I try to learn how to take the movement of life, and that's what I do with the images, as well.

How do you think post-production elevates your photography?

Most of the time I find photography alone to be incomplete. Sometimes even printing the collage is not enough. I would love to include my pictures in sculptures, structures--but right now I don't have the resources to develop it enough--working with stones, the urban or natural landscape. That's why I enjoy printing the work on fabrics or including them in a natural space.

What advantage do you have as a queer photographer?

Perhaps the understanding of the struggle that most of the oppressed live daily. The struggle of being whoever you are, with freedom. It feeds my work. Not that Im looking for it to do so, but I grew up in a small town, in public housing, where I had to fight for my freedom of being me. Back then, being queer was not even an option. It basically didn't exist for me because nobody was talking about it where I'm from, so I was pissed and sad a lot. It was another thing that I had to repress and the context was already not simple. So maybe that's the advantage: a better understanding of some situations.

These photos in particular focus mostly on the same subject. Who are these individuals and why you were drawn to them?

At first I wasn't analyzing this attraction. It was beyond my understanding--impulsive. As of now, everything was instinctive. I don't like the notion of growing up the way society has defined it with responsibilities and retention of impulses, so I guess it's quite normal for me to photograph people who don't yet fall into this system. In a more general context, it's all about energies, what they release from themselves, and the honest attitude. I don't like players. There is the one Puerto Rican boy I work with a lot; his name is Tadzio and he's one of the people I love the most. I know him very well and I've watched him grow. He always had the energies I could identify with. We're family.

You've described your work as reflecting teenage rebellion. Why?

The reflection is modest, still in the details, in the look of someone, the way he moves, the energies released... it's all very subjective. And why? Because I had to live tough shit when I was a kid and a teenager, like a lot of people. I had this unconscious capacity of going through it, almost like in automatic pilot, without realizing, and surviving. And then one day you're an adult and you find that all the wounds are here, waiting for you to take care of them. That's hard. I'm looking for this beautiful unconscious courage again.

Do you see yourself in the images you create?

I think that's the most personal I can get: my subjects are my studies about myself. They're what I'm looking for in me--studies from my soul, but also about the energies in and out of the body. My subjects are all boys, for now, and boys for me are more representative of this freedom of the body. I personally don't conform to stereotypical gender rules. When I think about myself and my upbringing, in nature or in public housing, with a lot of struggle and also a lot of freedom being by myself, with no real structure around me, I realize I share a lot in common with these boys and their energies. But it can be very delicate--a fine perception.

For more on Camille Rouzaud, visit www.camillerouzaud.com.