Poet Chen Chen spent the first three years of his life in Xiamen, China, an infancy he locates as being "largely make-believe, my vast intended country" in his poem First Light. Later in the poem he writes about coming out as gay at 13 to a violent family audience.

Now 28, Chen is a Kundiman and Lambda Literary fellow, Managing Editor forIron Horse, an Editor-in-Chief of Underblong, and is pursuing his PhD in English and Creative Writing at Texas Tech University, where he teaches Poetry and Nonfiction. Chen is, by reasonable standards, a grown-up.

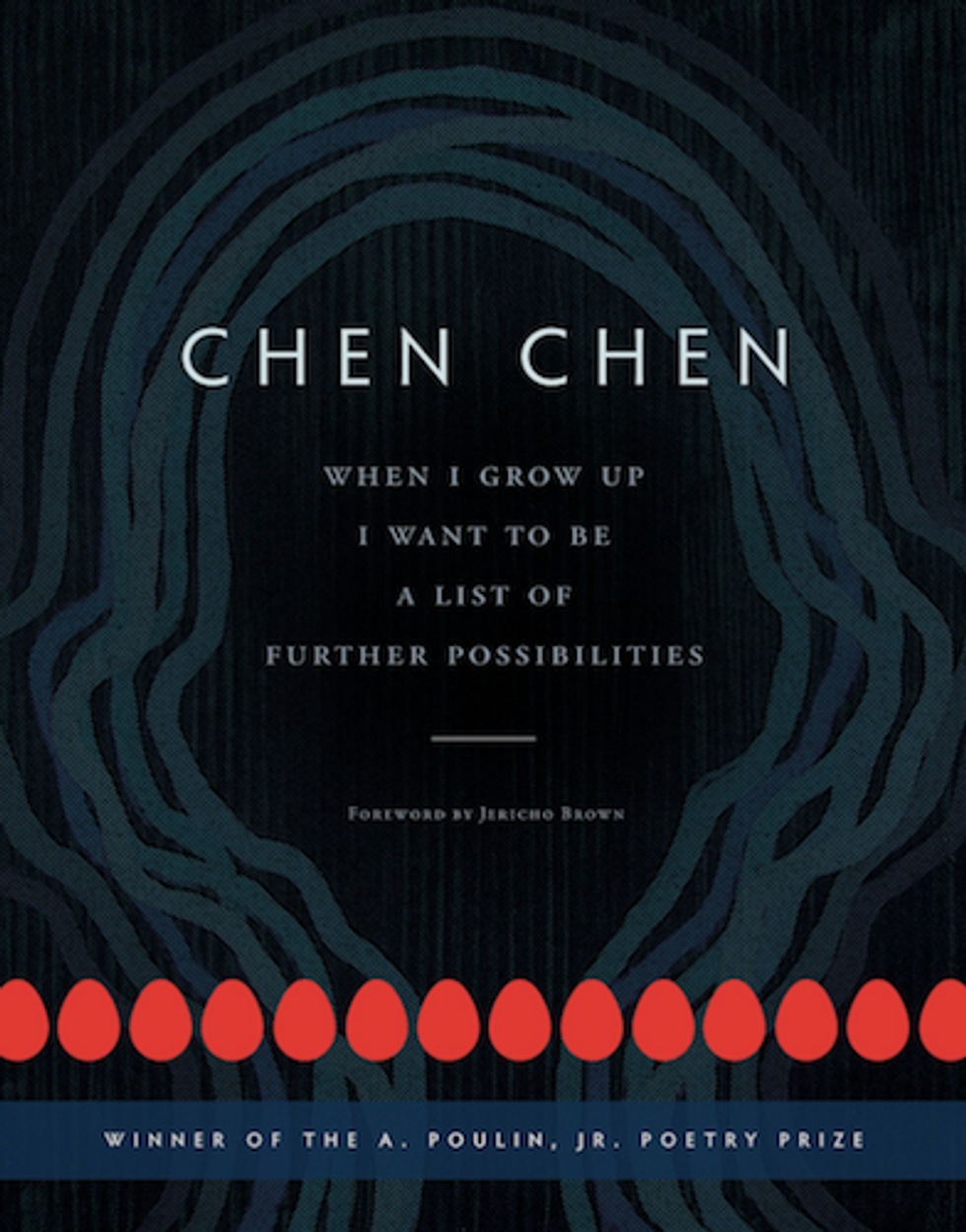

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities is Chen's first full-length collection of poems, selected for the 15th annual A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize. The book opens with Self-Portrait As So Much Potential, "Dreaming of one day being as fearless as a mango." Tender as ripe fruit, Chen elucidates: "As friendly as a tomato. Merciless to chin & shirtfront." The reader is not biting without consequence. So begins a collection of poems, buoyed by a sense of discovery, looking for all the configurations of family and futurity possible.

Chen writes with his own bit and bloodied tongue firmly in cheek, leaving droplets on the page from what he wanted to say sooner. In Poem In Noisy Mouthfuls he writes of, "Trying to get over what my writer friend said, 'All you write about is being gay or Chinese.' Wish I had thought to say to him, 'All you write about is being white or an asshole.'"

OUT caught up with Chen to discuss When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities, in which he writes about the intake of "racist comments from people who claim to be postracial. Or kind." Chen's poems expose the shortfalls of anti-racist rhetoric. His debut belongs in conversations about the arts of the possible and how much further we can go.

OUT: The title When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities references growing up as a threshold not yet met. How do you stay young at heart?

Chen Chen: Writing poems. Daydreaming that I am an international pop star instead of writing poems. Eating Twizzlers and drinking soda (which is not so good for my physical youth).

Poems keep me "young at heart" because they keep alive my capacity for surprise and my absurd love of sound. Musical language doesn't really make any sense. Blue rhymes with true rhymes with new--an irrational delight... or maybe a different kind of logic? "Young at heart" means questioning. Growing up means that, too.

While allowing me to play around like a kid, poems also push me to keep reimagining what growing up looks like, means. The title suggests that our definitions of "grown up" can change, expand, get weirder, and that the most exciting growing up involves things we haven't yet considered, some way of being/making that doesn't yet exist. Like, a queer Asian American pop star who sells out stadiums and whose main instrument is the xylophone.

What advice do you have for young queer people struggling with family members who don't accept them?

Please know that you are loved, loved, loved. I love you and I am writing for you and working to make things concretely more livable for young queer people. Many people, including people you haven't met yet, love you and are writing for you.

Find the friends, teachers, guidance counselors, coaches who support you, who listen to you. Someone who can talk to your unsupportive family on your behalf or help mediate a conversation. Join your school's GSA. Start your school's GSA or a group that configures shared identity and solidarity in other ways. Your own ways. Listen to yourself. Keep exploring. Check out queer writers, queer musicians, queer YouTubers, queer visual artists. Queer people are making beautiful worlds!

It's important to say: your heartbreak is real. There is nothing wrong with you if you continue to feel heartbroken. Your emotions, including your sorrows, are real. Always. In my book, there is no "happy ending" to the conflicts between unaccepting, homophobic parents and a queer son. The lack of reconciliation is my reality. Maybe that's your reality, too. You are still amazing and if you've had to make the choice--for your own safety and health--to cut off communication with family members, I see you, too. I love you, too.

You dedicate your poem Spell To Find Family to Kundiman, an organization dedicated to Asian American literature. What are some ways writing is a spell to help you find your diaspora?

I wrote the first draft of the poem during my first Kundiman retreat, [which] was life-changing. For the first time in my life I was surrounded by a whole, mighty cohort of Asian American poets.

Friendships were forged during those handful of days that still remain central relationships for me, as a heart seeking other hearts. I'll always remember Marilyn Chin sitting with us in a big circle, looking at all of us, and saying, "You are the future of Asian American literature." This poem is celebrating the possibilities Kundiman has awoken, the friendships and communities that are now being built.

The poem is interested in queer forms of kinship and in a diaspora that isn't bound to biological family nor patriarchal structures. Finding family means something much more unpredictable and constantly reinvented.

Writing can be a spell in the sense that I get to conjure pasts and futures, memories and dreams...I name and draw strength from predecessors, the Asian American writers who've come before. I name and hold close those who are writing alongside me now. I try to create a good expansive caring space for those yet to come, but god, I'm so joyful thinking of these writers whom I will get to tell, "You are the future of Asian American literature."

You amplify the voices of queer people of color as an editor and an educator. How important is being a mentor to you?

Deeply important. In every role I take on, I try to support fellow queer people of color. I don't ever want to assume that "queer people of color" means one type of experience or writing.

I was discussing with my Intro to Creative Writing students a book called Imago, by the poet Joseph O. Legaspi. Joseph is queer and Asian American and a co-founder of Kundiman. Joseph's background and poems are so different from mine.

He writes about a childhood in the Philippines and immigrating to the United States as an adolescent. He writes about Los Angeles and New York City. He writes about sexual awakening, these landscapes. He writes about circumcision, which in his experience was performed when boys reached the age of eleven or so. He writes in ways that make my Texas Tech University students cringe and shift around in their seats.

Many of these students have had conservative upbringings, conditioned like many young people in the United States to treat queerness, gender roles, and frank discussion of bodies as taboo. Ultimately, the discomfort my students felt was a productive sort that became conversation. We talked about cultural norms and assumptions--how bodies or certain body parts and just the fact of nudity get sexualized in American culture.

In your poem Talented Human Beings you present a Pop Quiz about people whose names and legacies we may not know. What Pop Quiz would you like to pose to OUT readers?

What was the Chinese Exclusion Act? How long was it in effect? If you already know the answers to these questions, when and where did you learn about this history?

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays