The Leslie-Lohman Museum for Gay & Lesbian Art has been a staple of New York's SoHo neighborhood for as long as the city can remember. But it wasn't always a museum. Back in 1969, after the Stonewall riots, the need for a safe space for the gay and lesbian community to gather was dire.

Charles Leslie, a performing artist, and Fritz Lohman, an interior designer, got together, both romantically and professionally, to set up an exhibition space in their loft in SoHo. The point was not only to exhibit the work of the community but also to provide an environment in which the voices of gay and lesbian individuals could be heard, broadcastedand discussed. As such, the duo created an oasis of LGBTQ art. "What they thought was going to be a small gallery opening became a big event where hundreds of people came in a weekend," says newly appointed museum director, Gonzalo Casals. When the AIDS crisis hit the community in the '80s, however, the stakes changed really fast.

Barbara Hammer, Lesbian Wedding Dewar's Style, 1977/2004 (Collection of Leslie-Lohman Museum)

With gay and lesbian people passing away at record speed, the need to preserve the cultural capital of the community was paramount. Casals explains, "during the AIDS pandemic, they started seeing how, when artists passed away, families would come in, clean the apartment, and pretty much throw out all the work. Not just work done by the artist but also work by other artists. In a very intuitive way, they realized that the whole visual representation of a generation was going to disappear." It's from this realization that the couple started acquiring much more aggressively, spreading the word that they were accepting donations, and actively expanding their collection.

This movement established Leslie and Lohman as one of the integral authorities during the AIDs crisis. While GMHC served as a medical resource and Act Up as a political one, Leslie and Lohman embodied and preserved the culture of the community. This came with a great responsibility. They sought to formalize the work they were doing in collection and create a foundation in the late '80s. But for 4 or 5 years, the IRS wouldn't give them the status because the word "gay" was in the title of the foundation. Thwarting threats from the police and the intolerant passersby, the foundation eventually claimed its rightful status and ultimately transitioned into a museum in 2011. Today, the collection contains over 25,000 works, including archives, artist letters, publications and many more. "We're basically the only LGBTQ art museum in the world," says Casals.

Nan Goldin, Clemens at lunch at de Sade, 1999 (Collection of Leslie-Lohman Museum)

Around 6 years after acquiring museum status, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art has finally expanded their space, offering museumgoers a larger array of work to savor. To celebrate its reopening, curators have put together Expanded Visions: Fifty Years of Collecting, an inaugural exhibit showcasing striking work from the museum's collection to more accurately portray the recent history of the LGBTQ community. "The typical approach to [representing] our community is usually by identity; so the gays here, the lesbians there. For this exhibition, the curators organized it by themes. This allows you to see queer culture as a whole. You can see three centuries of work in just one wall," explains Casals.

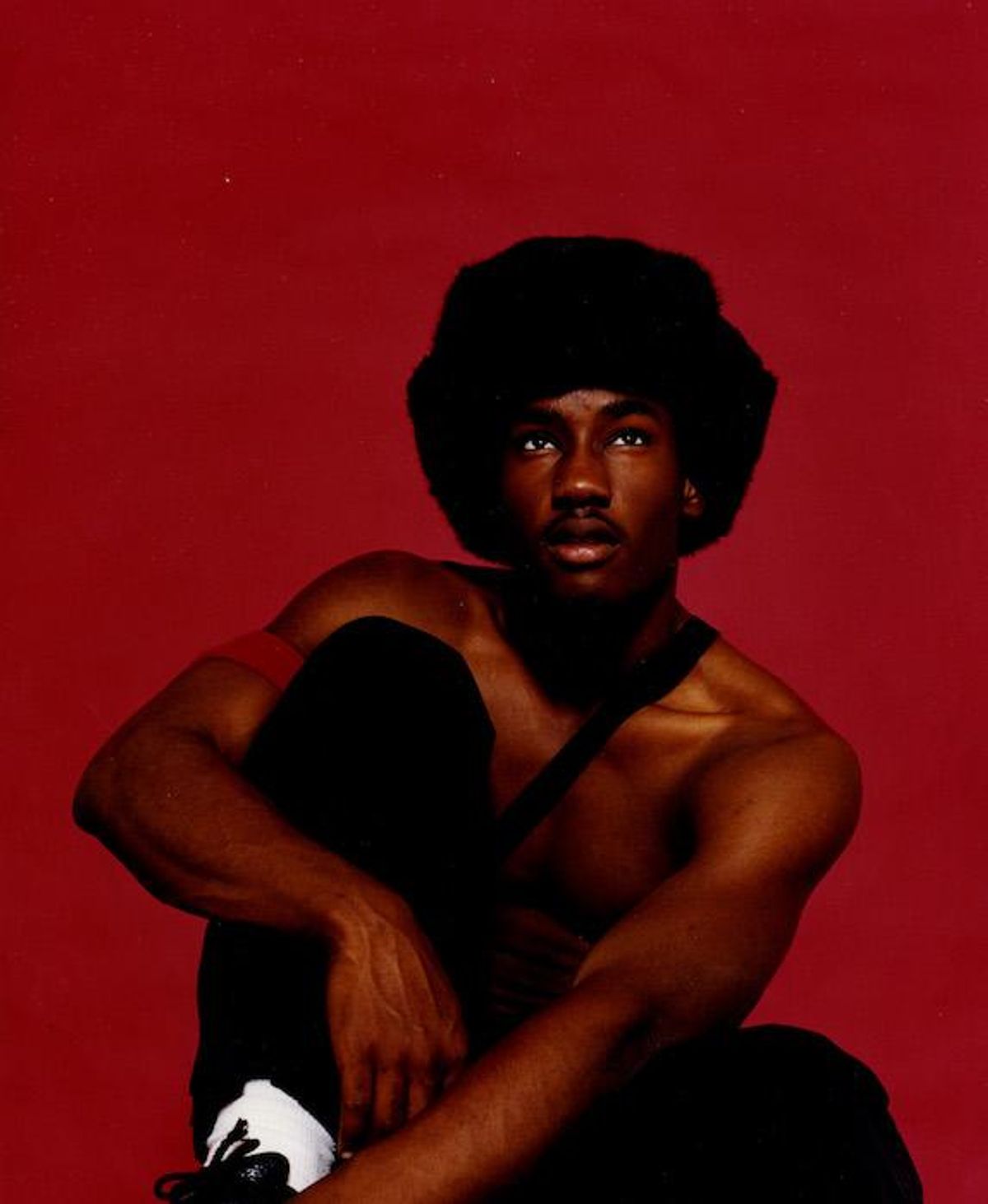

The museum director said the collection is heavy on erotic male iconography, as this is what Leslie and Lohman originally sought out and what was popular back in the '80s. Now, the fad has changed and notions of queerness are so much more complicated. To that effect, the show is divided into very distinct sections: portraiture, the queer utopia, aids pandemic, male iconography, political works, relationships and self-portraits. To present a community thematically makes sense, especially since the works on view demonstrate a strong emphasis on diversity and inclusion. For example, having works by Mickalene Thomas, Nan Goldin, Cassils, and Ernesto Pujol in conversation with that of Catherine Opie, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andy Warhol truly places each artist within a larger context.

Installation, Expanded Visions: Fifty Years of Collecting, at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art

Casals explains that "it's really about getting a whole new set of voices to add to the conversation. All that translates to the idea that each person has his or her own definition of what queer means. It's not about coming up with a definition of queer and then representing it, it's about representing that exploration." To do so, the museum has established a special fund for acquisitions to expand its collection. It will invite curators to conceptualize exhibitions with works both from the collection and from other museums. Programming will also be a big part of the museum's new iteration, with an emphasis on community-building and on the contextualization of queerness throughout history. "When you're queer, you need to be a little bit of an anthropologist because we're constantly looking for traces of queerness in history and society just to make sense of who we are," Casals says.