On September 20, 2011, the long national nightmare that was "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" ("DADT")--a Clinton-era policy that barred open military service by LGB individuals--came to an end under then-President Barack "Is It Too Late for 4 More Years?" Obama. Eventually under Obama, transgender people were granted the same freedom, but then, on July 26 of this year, President Trump sent a tweet that signaled yet another attempt to turn back the hands of time and progress. While the future of Trump's proposed ban will probably, like so many other issues, be sorted out in court, the damage has already been done: Trans soldiers serving their country know now that their commander-in-chief doesn't support them.

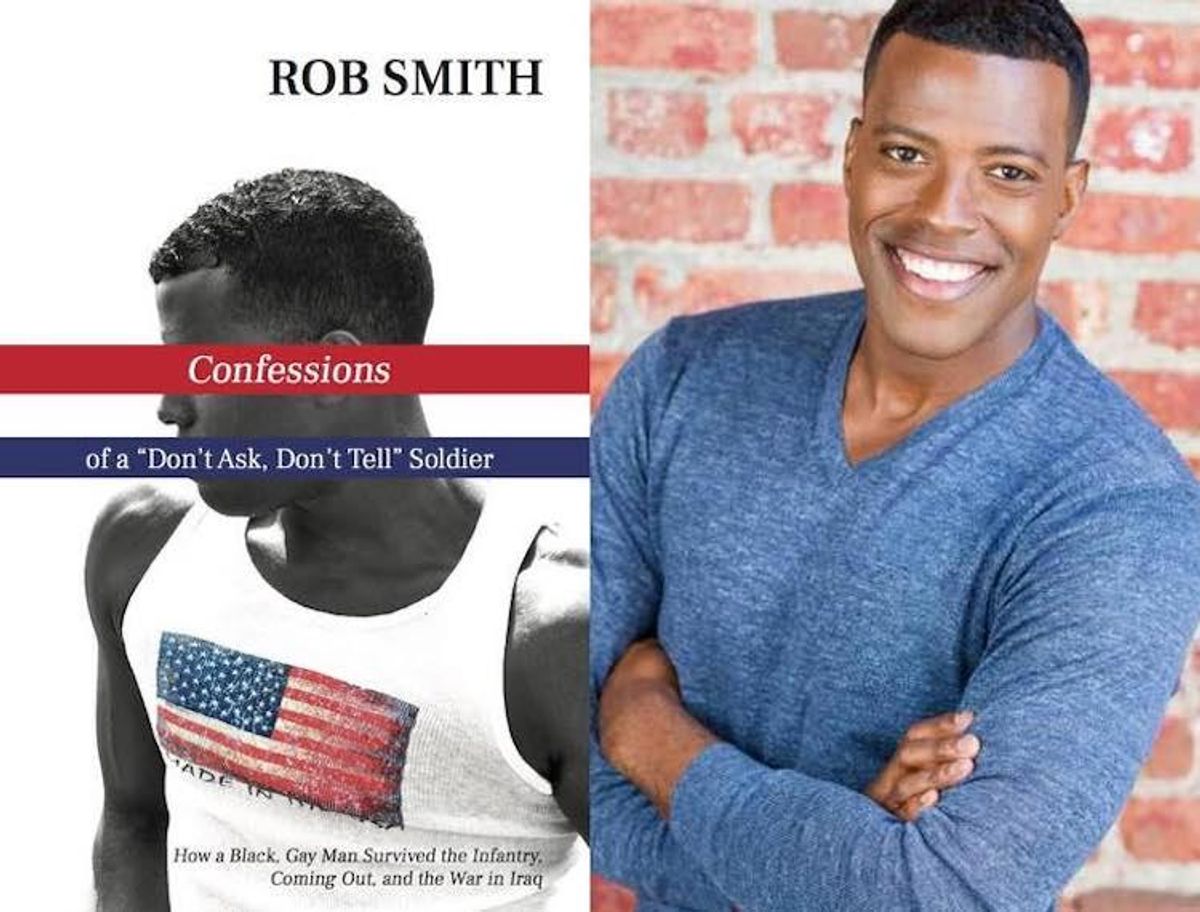

Rob Smith knows how they feel, having spent five years in the U.S. Army under the shroud of "DADT." As an Infantryman, he was deployed to Kuwait and Iraq, for which he earned the Army Commendation Medal and Combat Infantry Badge. In November 2010, Smith was arrested with 12 other military vets and civilian activists in front of the White House gates for protesting "DADT," only to be invited to the ceremony celebrating legislation to repeal the law the following month. In his newly released memoir, Confessions of a "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" Soldier: How a Black, Gay Man Survived the Infantry, Coming Out, and the War in Iraq, Smith recounts coming to terms with his sexuality in the hypermasculine and homophobic U.S. Army during the initial invasion of Iraq.

OUT: Why did you want to write this book?

Rob Smith: This book would've really helped me out as a young black gay kid struggling with my identity. The fact is, even in 2017, most military stories are still written from the point of view of a straight white guy. What is the last military-themed movie or TV show that you saw that didn't completely center whiteness and maleness? Take a second to consider that. I wanted to share a story about class, race, coming-out, and the military from the vantage point of a black man. This is quite simply something that has never been done before.

And why now?

Well when people ask me to describe the book, I say it's Moonlight meets American Sniper. The success of [the former] is so groundbreaking that I thought it was a really good time to tell this story and that people would be more receptive to it. America and the LGBTQ community are more open to issues of race and class right now than either has been in my lifetime, and the time just felt right. My biggest hope is that maybe the success of Moonlight could open the door to this story being on the big screen someday.

Related | A Moonlight Revolution: The Black Queer Experience Comes of Age in America

What were your initial thoughts on Trump's proposed ban on trans service members?

I find the ban outrageous, infuriating, and unacceptable. You know, I interviewed a lot of Trump supporters--even gay ones--when I worked with NBC News during the 2016 election season. I understand the reasons why people voted for Donald Trump. Those interviews gave me a window into that mindset. I'm not surprised that this administration is becoming an absolute disaster, but I am surprised at how cruel some of its actions have been, particularly with this ban and now with the DACA blowup. I'll always be proud to be an American. I love this country. But everything that is going on at the top right now is enough to shake that love to the core.

Do you fear the return of "DADT"?

On one hand I don't, but on the other I realize when they come for one group of people, another can't be too far away. That's why it's important for me to speak out against the ban. That's why it was important for me to go on CNN and say unequivocally that this is wrong and discriminatory, because if there aren't enough voices out there speaking out right now, GLB soldiers could very well be next.

What words of advice or encouragement do you have for LGBTQ members of the U.S. military?

I struggled to come to the realization that my service is and was as valuable as anyone else's, regardless of my sexual orientation. I need for these currently serving soldiers and veterans to know that their lives matter and their service matters. Keep fighting for what's right, and play the long game.

Below, an excerpt from Confessions of a "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" Soldier:

THE NIGHT I decided to end my life, I sat alone in my barracks room just a few weeks after I came out to my mother. In the weeks after my admission to her and her subsequent rejection of it, I'd sunk into a deep depression. I was lost, lonely, and consumed with self-hatred about my sexual orientation. I knew the fact that I would never be like other people was what bothered her the most. Though I wanted deeply to talk to someone about my feelings, I knew I couldn't. I wanted escape. I figured that the nothingness that death would bring would certainly be better than anything I was experiencing at the time.

If I told anyone about why I wanted to kill myself, even a Chaplain or a mental health person at the VA Hospital on base, I would be discharged under the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy. I stood to lose everything even if they helped me beforehand. I knew very little about how people went about suicide, but knew that I didn't have the stomach to slit my wrists. I remembered vaguely reading about how any pills taken in large doses could result in death, so I'd bought an economy- sized bottle of Tylenol from the gas station that was walking distance from the barracks, meaning to partner it with a bottle of cheap vodka I'd swiped from an impromptu party that some soldiers in the building had thrown a few weeks back. I walked into the bathroom in my barracks room and closed the door, stealing one last glimpse at the night sky just beyond the window.

The fluorescent lights bounced against the cold steel of the counters, toilet, and tub. It served to create a harsh whiteness that was almost clinical, as if I were in a hospital bathroom. I sat on the tile floor and curled against the tub, feeling the hard steel pressing into my spine. I looked down at the bottle of pills in my left hand, the bottle of vodka between my knees, then at the telephone in my right. I couldn't remember picking up the phone to bring it into the bathroom, and found myself dialing my sister's number as if in a daze. My sister and I had never been extremely close, but that night I didn't know whom else to call. I closed my eyes and exhaled in relief as I heard her voice on the other end of the line. Her tone went from annoyance to concern to frantic damage control as I found myself telling her about what I had planned for the evening.

For hours and hours that night, she listened to my problems and concerns as nobody else had before. She told me that she would always love me no matter who or what I was. I sobbed as I listened to her words, and I could hear her own tears and choked up voice through the other end of the phone. After many hours, when she was absolutely convinced that I'd abandoned my plans of suicide, she hung up the phone and went to bed. I sat in the bathroom that night thinking and crying for a very long time, and eventually cried myself to sleep. When I woke up the next morning, the first thing I saw was the bottle of pills that had rolled out of my hand and into a dark corner behind the toilet, abandoned. I picked them up, placed them calmly in the medicine cabinet, and left the bathroom.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right