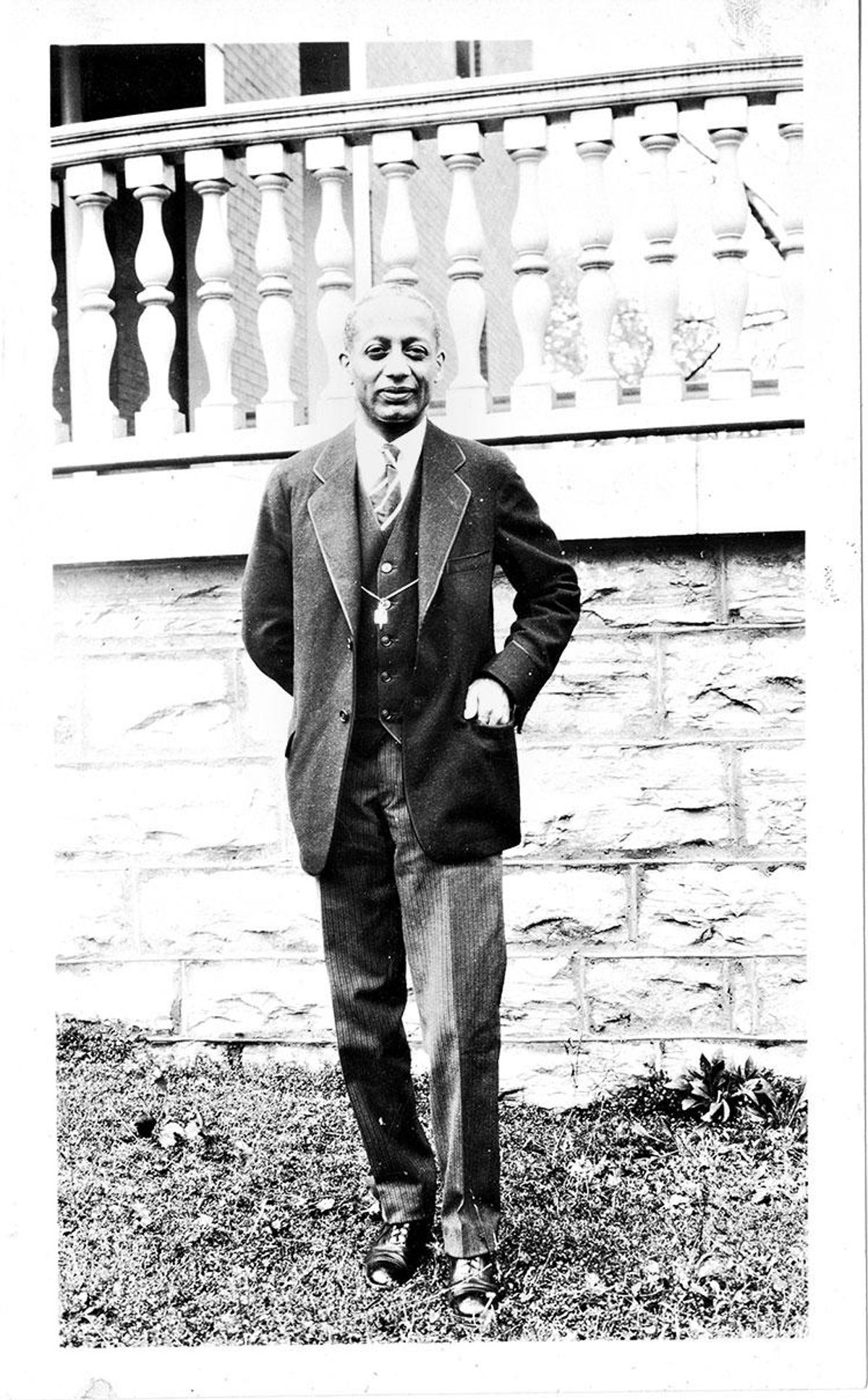

Philosopher, scholar, journalist, and educator, Alain Locke is considered the Father of the Harlem Renaissance for his support of, and writings on, the cultural movement that empowered generations of black people. A Harvard graduate, Locke was named the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, but he still experienced racism and discrimination at Oxford--a particularly heavy blow considering, like many black artists and intellectuals, Locke sought in Europe freedom from America's ceaseless oppression. Compounding his difficulties as a black man, Locke was a homosexual, and the following edited excerpt from The New Negro, Jeffrey C. Stewart's definitive new biography on the scholar, details his unrequited attempts at wooing legendary Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes.

On Hughes's last day in Paris, the two of them took a "trance-like walk up the Champs Elysees." At the Arc de Triomphe, they turned east, walked down the avenue Foch, with its sumptuous lawns and townhouses, and entered the Bois de Boulogne, Paris's largest and most beautiful park. On a hot, August afternoon, the heavily wooded Boulogne, with its two lakes and marvelous waterfall, had a magical effect on Locke. After a brief evening stop back at Hughes's rooms, Locke, rather than his protege, had fallen in love.

The next day, August 9, Hughes left on a trip to Italy...Hughes agreed to meet Locke later in Venice, but Locke could not wait until then to continue his courtship. He opened up his heart to Hughes in a letter written the day after he departed.

"Today the atmosphere is like atomized gold, and last night you know how it was--two days the equal of which atmospherically I have never seen in a great city, days when every breath has the soothe of a kiss and every step the thrill of an embrace. I needed one such day and one such night to tell you how much I love you, in which to see soul-deep and be satisfied. God grant us one such day and night before America with her inhibitions closes down on us. And then perhaps through prosaic hours and days we can keep the gleam of the transcendental thing I believe our friendship was meant to be."

Apparently, at the end of that night, Hughes granted Locke some undisclosed intimacy--a hug, a kiss, or something more--and afterward, Locke was eager for a lot more. Arnold Rampersad suggests Locke's letter stunned Hughes. While he had developed an intimate friendship with Locke, he had not fallen in love with him. One can readily understand how Hughes felt: Locke was crowding him, pushing him into a sexual relationship that he did not want. Moreover, the request for further intimacy carried a threat. Locke might withdraw his offer to subsidize Hughes in his quest for a college education. He responded with innocence, ignoring for the moment the reality that he wanted Locke's financial help without having to put out sexually.

Locke did not want a prostitute--he wanted a companion who lived with and inspired him. His financial "carrot" emerged out of his insecurity that as an aging gay man he could not attract a young man of quality like Hughes without some leverage. What he longed for, of course, was for Hughes to love him.

But he'd gotten what he needed from Hughes. Locke was able finally to pen the first draft of his essay, "The New Negro." Locke's summer romance had achieved its desired effect of inspiration for a new statement about what it meant to be a Negro in 1920s America. For the first time, Locke was able to sketch in writing a compelling image of a New Negro that was not fundamentally elitist. Locke may not have gotten love from Hughes. But he got something he needed even more: intimacy with a thinker with affection and affinity for the black working class.

The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke by Jeffrey C. Stewart is published by Oxford and available now.