Kia LaBeija loves looking at people's closets with her artistic eye: the colors, the textures, what the garments say about the person who hung them up. The 28-year-old artist and Overall Mother of the House of LaBeija -- yes, the legendary house Crystal LaBeija founded in the 1970s that changed ball culture forever -- remembers going into her grandmother's closet as a kid and marveling at all of the gorgeous fabrics draped overhead.

"A person's space tells you a lot about who they are," LaBeija says. "My grandmother had a big closet filled with very beautiful clothes: a lot of traditional Filipino gowns and some very classic-looking dresses from the '70s. Everything always fit her so perfectly. Even towards the end of her life, when we'd go running in the morning, she'd wear this cute little fitted red Adidas suit with her makeup done and everything. I always thought of my grandmother as a Filipina glamazon -- always very together, very poised, and elegant."

Intimate memories like these form the basis of LaBeija's photographic work. Mixing portraiture and tableau, she recreates those moments to varying degrees of realism, capturing how she felt rather than what literally happened. In a similar vein, her work is often set in the bedrooms and bathrooms where those scenes actually took place, instead of reproducing them in a studio.

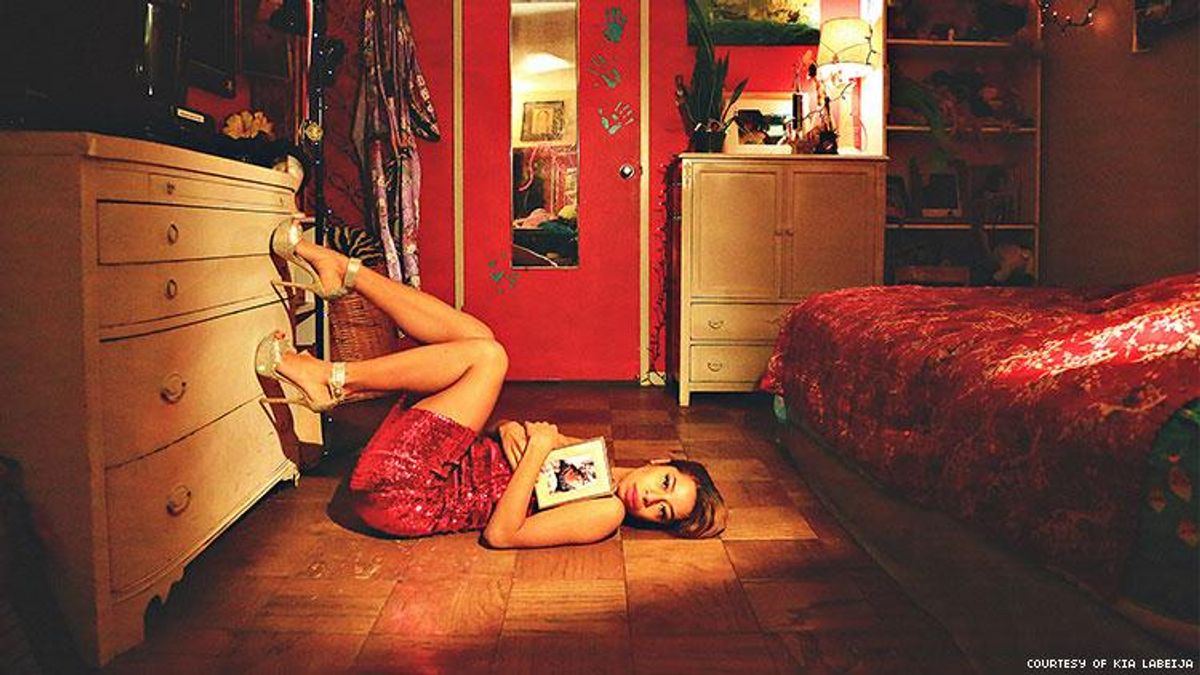

"I'm really interested in lived experiences and how they relate to particular spaces," LaBeija says. "24 is my first comprehensive body of work. The images in that series come from my relationship with being born with HIV, living with HIV, having an HIV-positive mother, and losing my mother to an AIDS-related illness." One of these images, Kia and Mommy, shows LaBeija lying on the floor of her bedroom wearing a red sequined dress and glittery gold platform stilettos, her ballroom training evident in her clean lines and razor-sharp angles. She's staring straight into the camera, holding a photograph tightly to her chest. It's a portrait of her mother -- the same photo she cradled in her sleep for years after her mother's death. "In 2014, when I was making 24, I was feeling sad that I couldn't share this new, exciting love of portraiture and photography with her," she says. "And then I realized I still could. That's the magic of art."

LaBeija grew up in New York's Manhattan Plaza -- a subsidized artist housing complex that opened in 1977. She's been living in Los Angeles for the past year with her partner Taina Larot, a 33-year-old artist and arts educator. The two moved out west to have a place of their own where they could recharge when not traveling around the world for work.

Since moving to the West Coast, LaBeija has had her debut solo show and begun working with art galleries for the first time, a learning experience that she hopes doesn't jade her. It's not that she has an issue with making money off of her work -- she wants to earn a living as an artist -- but courting a potential buyer's favor carries its own set of complications for marginalized artists.

The fraught power dynamics of the industry are well-documented: In 2014, art and culture blog Hyperallergic analyzed ARTnews's annual top 200 list of art collectors, deeming them disproportionately white and male -- and all rich, obviously. As LaBeija's work depicts the pain and heartache of a queer, mixed, Black woman, she wonders why a wealthy white buyer might want to own some of that imagery and what they'd like to do with it.

"As a woman, a woman of color, and a queer person, I don't know how comfortable I feel about putting my body in the hands of affluent, privileged white people who turn around and sell my body to other affluent, privileged white people," LaBeija says. "Thinking about that is a bit painful for me, to think that my life -- everything that I've had to endure that may have been painful or traumatic in my life -- may sit in the back of someone's closet." She feels similarly fraught about working with white gallerists who then sell her work to white collectors: "You're putting your white name on my Black body and making half the profit. I did 100 percent of the work; I want to make 100 percent of the profits."

On the subject of work, LaBeija says she and her partner have been working intensely together over the past 18 months on an ambitious mixed media project called Wom(y)n with a Y that combines film, installation, and print. "She understands me and who I am more than anybody in this world," she says of Larot. After a year away from home, the two plan to move back to New York by the end of 2019. "Something about it seems new. Leaving home makes you appreciate and understand it more. It lets you come back with fresh eyes."

To read more, grab your own copy of Out's March issue featuring "The Mothers and Daughters of the Movement" as the cover on Kindle, Nook and Zinio today, and on newsstands February 26. Preview more of the issue here. Get a year's subscription here.