NPR host Ari Shapiro is ready to talk — this time, about himself. After a career spent listening to others, he’s telling his story of a job that has taken him around the world and even sparked creative pursuits like performing with the band Pink Martini and the legendary bisexual entertainer Alan Cumming.

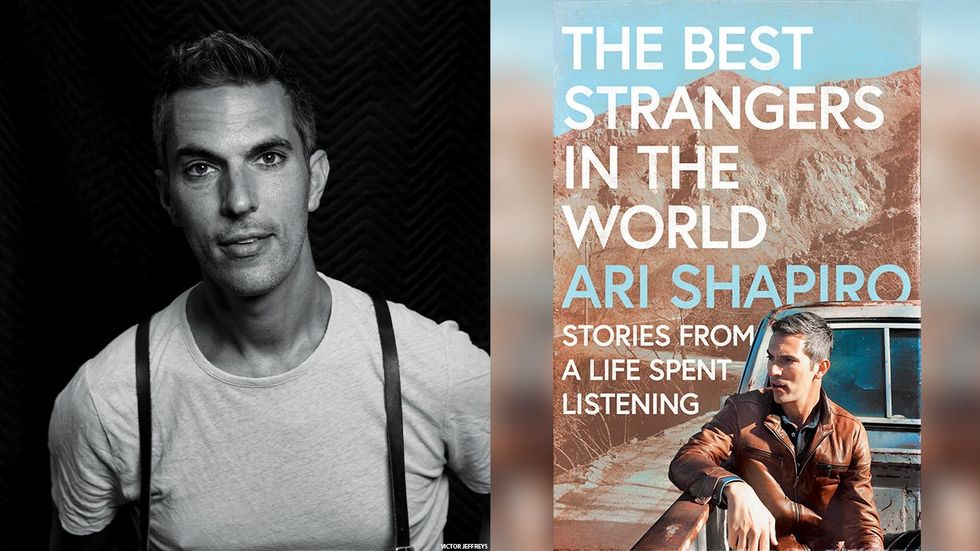

The cohost of NPR’s All Things Considered and former White House correspondent gets personal in his memoir-in-essaysThe Best Strangers in the World: Stories From a Life Spent Listening. The 44-year-old shares everything from the story of his relationship with his husband, Mike Gottlieb, to why he likes sweating the way he does to never liking the question “What’s your favorite interview?”

“For the more than 20 years that I’ve been a journalist, it sometimes feels like when I set out to tell a story, I have to put myself in a box because it’s not about me. It’s not supposed to be about me. But I felt like it was time to open the box and see what was inside,” Shapiro says.

In cracking open this box, Shapiro realized that his work in media has influenced who he is today. “I wanted to explore that in the book and try to draw connections across some of these stories and experiences that may feel very different from one another,” Shapiro says. “Whether that is covering wars and revolutions or singing with the band Pink Martini or traveling aboard Air Force One with the president of the United States.”

Shapiro begins The Best Strangers in the World discussing his youth as a Jewish kid in North Dakota before moving in his teens to Portland, Oregon, where he was out in high school. In fact, The Best Strangers in the World is a love story to Shapiro’s queer identity. Nowadays, the buttoned-down reporter knows he might present as fairly conformist — but that would be a superficial reading.

“Sometimes, I’m a secret agent f****t behind enemy lines; other times I just want to impress your parents. I itch to torch oppressive and exclusionary institutions, even as I long to prove myself worthy of membership in them,” Shapiro writes in his book. “To rewrite a slogan from a T-shirt that I’ve spotted at countless Pride parades over the years, I am both ‘gay as in happy’ and ‘queer as in fuck you.’”

In one chapter, Shapiro highlights the yearly sojourn he takes to a commune of Radical Faeries in Tennessee, part of a countercultural queer movement that began over 50 years ago. These faeries — who hail from the worlds of film, theater, visual arts, and other media — spend a week exploring their creative depths, a transformative experience for Shapiro. “When I spend time with the faeries, I’m reminded of what it means to move through the world with an attitude of radical acceptance with an insistence on being present in the moment that you’re in, with an openness to new ideas and people,” Shapiro explains.

It is also valuable time spent with queer elders. “So much of LGBTQ life is divided by generations, and since we are not, for the most part, raised by queer people, we don’t often get the chance to talk to queers in their 70s or 80s or even 90s about their lives, and they don’t often get a chance to share their lived experience, their wisdom, with younger generations,” he says.

Although he’s famous through radio, Shapiro is also known for his striking looks, which helped land him on Paper’s 2010 list of “beautiful people.” Shapiro is proud of this distinction due to the company he shared in the magazine’s pages: “When I look at the people who I’m on that list with, it’s not the best-dressed people; it’s not the people with the best bone structure. It’s the people who are doing creative, interesting, and beautiful things.”

It’s those assets that he prizes. “Ultimately, we will all grow old and wrinkled one day if we are lucky enough to live that long,” he says. “I hope that I am, and I look forward to being one of those elders who does not have to think about whether beauty is a currency to be spent.”

In 2019, Shapiro began a cabaret show with Cumming called Och and Oy! — a play on Cumming’s Scottish identity and Shapiro’s Jewish identity. In his book, Shapiro shares the start of their collaboration, from planning sessions in D.C. to celebrating a successful show at an underwear party on Fire Island.

Shapiro has also performed with the band Pink Martini for years, an experience he likens to being in a “well-oiled machine” run by a large ensemble of singers. However, “when Alan and I do our show together, it is really a pure collaboration and creation that the two of us do, which is such a surreal experience to be able to make something like that with somebody who is so revered.”

Nowadays, Cumming is a friend, a role model, and a big brother figure. “[Cumming] is insistent on enjoying life,” Shapiro says. “Alan, to me, represents squeezing every drop of juice out of the orange and just savoring it.”

Like Cumming, Shapiro has also been a face for activism. In 2004 he married his partner in San Francisco when then-Mayor Gavin Newsom began issuing licenses to same-sex couples. (He and Gottlieb first met as students at Yale University in 1998.) Their ceremony was recorded by local news crews, and the footage became a fixture for years on MSNBC and other national networks in marriage equality reporting.

The 2004 marriage licenses issued by Newsom were later nullified by the California Supreme Court, which “means that today Mike and I are, technically, not legally married,” Shapiro writes in his book. The Best Strangers in the World debuts in a time when marriage equality is once again in the line of fire from right-wingers, along with transgender rights.

“I don’t know whether I take solace in this fact,” Shapiro says of the book’s pushback against a new era of anti-LGBTQ+ vitriol. “But I’m certainly aware of the fact that throughout history, queer people have had to fight for our right to exist, and that has taken different forms in different times. Adversity is real. But also, adversity is sadly consistent, and learning not only to exist but to flourish and thrive in the face of adversity has always been essential to the queer experience.”

And Shapiro is thriving. That queer experience influences how he approaches journalism, a job he continues to love.

“It is so exciting for me to wake up every day knowing that in my job, I’m going to learn about something I didn’t know about at the start of the day,” Shapiro says. “And when I’m out in the field, I get to parachute into people’s lives who are generous enough to confide in me about their hopes and their fears, their dreams, and their experiences. It feels like a place of privilege, and I never get tired of it.”

This article is part of the Out March/April issue, out on newsstands April 4. Support queer media and subscribe -- or download the issue through Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.