The first book I ever read by Larry Duplechan was Captain Swing, and in it, there’s what I call a “jazz paragraph” that runs on in the most melodious of ways. In the passage, our protagonist Johnny Ray Rousseau rhapsodizes about the journey on which music takes him at an almost constant rate. The paragraph zigs and zags, but there’s a beat and a rhythm that permeates the soul of the lucky reader. I remember also having read books from the beloved Buddies Cycle series by Ethan Mordden and thinking that while the two were similar in their semi-autobiographical approach, Duplechan’s protagonist was Black, something I hadn’t really read in the mid-'90s.

Duplechan is known for being a pioneer in Black queer literature. His first novel, Eight Days a Week, introduced modern troubadour Johnny Ray Rousseau as he juggles between his two passionate loves: music and romance. He must choose one, and the book is a touching reimagining of Duplechan’s own life. Then in Blackbird, which is often credited as a pioneering Black coming out story, we journey with Johnny Ray through his childhood and coming out experience. Many things set Blackbird apart from its narrative colleagues; while most similar novels ended in violence, homophobia, and death, Blackbird shared a reverence and passionate desire for homosexuality that was often celebrated. There may be instances of homophobia or characters who are not as accepting, but at the end of the day, being gay is just one part of an entire character who is wonderfully three-dimensional.

Blackbird was so popular that it spawned a movie by the same name. As a film, Blackbird screens more as an artistic interpretation rather than a true adaptation, but it does show the influence Duplechan had on writer and director Patrik-Ian Polk. Though the reimagining wasn’t necessarily faithful to the source material, it’s always electrifying to see Black queer creators make Black art. For decades so many of our stories were backburnered at best and completely erased at worst. And yet, there’s still a special place in the heart of the entertainer for entertainment and movies.

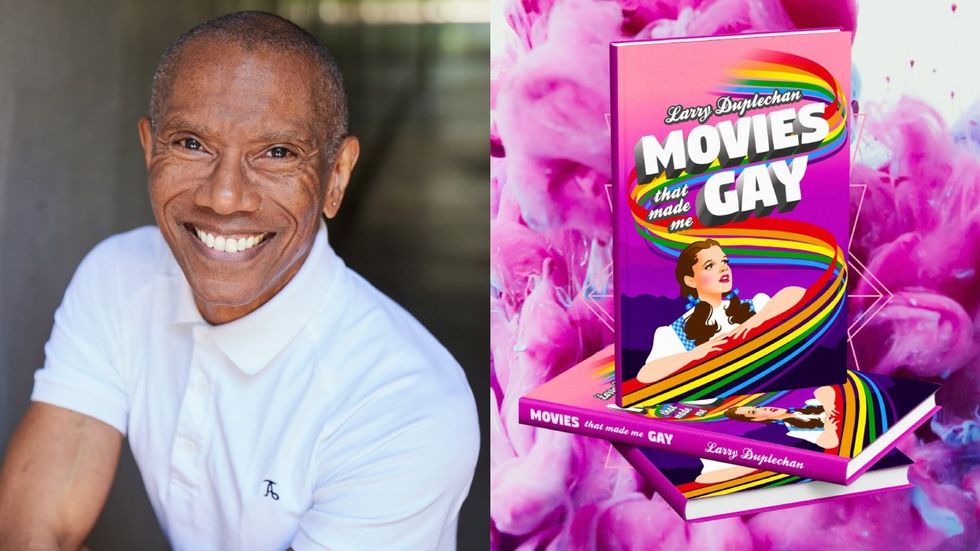

In his new book Movies That Made Me Gay, Duplechan says “movies gave my youthful oddness a certain ~flair.” He immediately felt a kinship with the actresses of yesteryear and the fantasies that seemed to be the living embodiments of his imagination. There’s a wonderful story recounting a betrayal of soundtrack choice by Duplechan’s mother on his birthday. Though she meant well, he’d asked for a very particular soundtrack and received a more generic rendering. Though it exposed him to the world of covers, it also renewed a determination in Duplechan to work hard to secure the things he wanted and soon, the authentic soundtrack was in hand. In Movies that Made Me Gay, Duplechan shares not only his love for movies, but how they shaped the person he is.

Published by Team Angelica, Movies That Made Me Gay is Duplechan’s first book in 15 years. It’s more than just a listicle, it’s the first book he’s written that can serve as an autobiography of key moments of his life. In a world where gay ancestors, especially Black gay ancestors, are rare, it’s refreshing to see Duplechan weave a colorful and rich tapestry into a living example of Black history. The book is broken into sections like “Black Movies,” “Gay Movies,” and “Classics,” a.k.a. all of the things that are extremely important to Duplechan. Then he presents a film and talks not only of its merit, but also the personal experiences that inform his takes. And then, he’ll tell you about all of the sequels. He talks about both The Wizard of Oz (1939), and The Wiz (1978), and also, The Women (1939) and the remake (2008), and the artful adaptation The Opposite Sex (1956).

There’s a natural sense of authenticity when Duplechan describes his memories of each project so succinctly and passionately. It’s the apex of every weekend bottomless brunch discussing Best Supporting Actress nominees, but this time in a book! I had the pleasure of sitting with Duplechan and talking about Movies That Made Me Gay, his influences and passions, his love of movies, and his thoughts about Blackbird (which are also eulogized in the book).

Team Angelica Publishing

Team Angelica Publishing

Out: I know your first love was music and you didn’t really set out to be a novelist. Tell me about why it was necessary to put your experiences to page?

Larry Duplechan: I am first a performer and entertainer, a show-off basically. In 1979 when I was trying to break into show business as a singer, the world wasn’t ready for it. I was Billy Porter when Billy Porter was in elementary school! In about 1971 after one of my cabaret sets, a woman walked up to me and she gave me her card. She says, “I’m a manager and I think you’re wonderful. I love your personality, can you butch it up?” and I said, “Thank you so much! No. I can’t.” and that was my first red flag that this was not going to be my time.

So concurrently, with being hit in the face with that pie of reality, I’m also in the seventh or something year with my partner, now husband, who is my biggest fan. I was always working a job and trying to pursue singing at night so we never saw each other. So as happened in Eight Days a Week, [my partner] finally said, “You know I’m your biggest fan, but I need somebody who's going to be here.” So when I decided to forego show business it took about a nanosecond to realize I had to express myself in some manner.

What made you decide to write more autobiographically and with a Black queer protagonist?

It was the early ‘80s and one could read every gay book that was published in a given year, and I did. I remember the real kick in the pants was when I read, The Lord Won’t Mind which is the whitest book in the world. Everybody’s white except the maid who says, “The Lord won’t mind.” I thought, “I need to write the book I want to read.” I wanted to read books about someone who was like me, so I created a protagonist that was basically me and put him in the books.

It’s a funny thing because it wasn’t so much that I loved writing. I don’t love the process, I never have. It’s very lonely and I’m a people person. Also, it takes a year before you know if they’re going to applaud you or throw the book at you, so there’s this weird time lag thing. So while I don’t love the process of writing, I do love having written.

I love that you said that because it’s a sentiment that I think many feel, but it’s not encouraged to be shared. I am glad that you stuck it out. With your musical background, there’s something of that that’s naturally birthed into your writing. It’s a part of your DNA. There’s a certain tempo, a rhythm, certain turns of phrase that just glide smoothly. Then there are times when it’s very staccato and pointed. Is this something that you’re conscious of in your writing?

Not really, but I love hearing you say that. I think it’s the DNA thing. Many of my biggest writing heroes are songwriters, and I’m not a bonafide songwriter. Though I’ve written here and there, it wasn’t really conscious. I am a singer and musician, so I think naturally there’s melody and harmony.

I love that Movies That Made Me Gay is not just a compendium of classic movies, but also a melodic retelling of the ways those movies touched you. We get more backstory, especially considering the thoughts and culture of the day. I love that you say the movies didn’t necessarily make you gay, but it certainly added a flair. What is it about these curated movies that make them yours?

Well, on a practical level, there are movies that just got shown on TV a lot. And I will admit some of them aren’t very good or even movies. A good example is Calamity Jane starring Doris Day. It’s both sexist and racist, but because it was shown on the Million Dollar Movies, my brother Lloyd and I watched it five times a week! We’ll have conversations with nothing but quotes from Calamity Jane because it’s just under our skin.

Then there were the 1933 and Busby Berkeley musicals, which, I think for a kid who was basically miserable, it was as far from my actual life as anything I could think of. That’s a large part of why I was attracted to these wise-crackin’ movies. I was acutely aware of the fact that I was not like my parents. I was not in most ways like my brothers or my peers. That overwhelming sense of other really required a level of escapism. So here was Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell and Shirley Temple, tappy tappy tap with Bill Robinson up and down the stairs. It was completely unlike 1966 Inglewood, and it was my escape.

Who is the ideal reader for this book? What kind of audience do you envision would be best served by it?

You know, the audience I had in mind when I wrote the book were people about my age. I think of it as a boomer book. So I pictured a 65-year-old, slightly punchy, working on their tan sitting by the pool in Palm Springs. Gay dudes reading this book, dishing it, talking about it, taking it with them to brunch over mimosas, and waiting for their egg white omelet like, “Did you see what that bitch said about Joan Crawford? Girl!” To my surprise and delight, people who are none of those things are turning out to be enjoying the book!

I like to think the other audience is people like me who have the Palm Springs spirit inside of them! Tell me, do you have more in mind, or are you just enjoying the moment?

I’m waiting to see what happens with the book and hopefully think about a sequence. I didn’t talk about All About Eve or The Philadelphia Story and others that didn’t quite fit this structure, but I’m hoping for more.

John Farrell Jr.

John Farrell Jr.

Movies That Made Me Gay is available from all major booksellers. For more on Larry Duplechan, make sure to follow him on Instagram.

Team Angelica Publishing

Team Angelica Publishing John Farrell Jr.

John Farrell Jr.