CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

Scroll To Top

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

People talk about emo now as if it is the gayest thing to ever hit rock. But in the early evolution of this hardcore punk offshoot, emo wasn't about guyliner and flat-ironed hair -- as Jason Gnewikow, the gay former guitarist and graphic designer of the band the Promise Ring, well knows. Ten years ago, he became he first notable musician on the emo scene to come out, and was greeted with a mixed reaction from fans. The irony was that many had already perceived the bands lispy singer Davey von Bohlen to be gay. (Hes not.)

The Milwaukee-based quartet also proved its trailblazing muster when it transitioned from punk's abrasive blare to power-pop and beyond: The combination of sugar-soaked hooks and distorted guitars on its 1999 album Very Emergency plays like the prototype for radio-friendly 21st century emo phenomenons like Fall Out Boy, while the Promise Ring's serious and much slower 2002 swansong wood/water reveals finessed balladry akin to later-day R.E.M. Its commercial failure helped bring about the band's demise soon after, but it proved how far emo could stretch years before Panic at the Disco.

Out gave Gnewikow a call in his Brooklyn studio to get this pioneer's 20/20 hindsight on Promise Ring's break-up, how his coming out affected the group, and what he thinks of bands that play gay.

Out: What's your perspective on the Promise Ring now?

Jason Gnewikow: It took up my entire 20s and I did lots of crazy things that most people don't have the chance to do -- touring all over Europe, Japan, playing on TV [Conan O'Brien]. In hindsight, I don't think it was something that creatively was completely flawless all the time, but I think things that seem cool at the time seem less cool later.

Is there something you wish you could've done over?

I wish we could've taken it less seriously towards the end. At the beginning of the band, we took it really seriously and it worked. But, like any band that nobody cares about, all the things you care about, nobody's looking at, so it's more your own obsession. We wanted to pay attention to every detail, and what that yielded was wholesome and good because it wasn't done with anyone [else] paying attention. We all came from this political punk rock background that was kind of miserable, but we liked all these other things that didn't exist in hardcore punk at the time. We wanted to be poppy and have fun. That was our weird obsession.

What do you think was the band's greatest achievement?

We went to England and recorded wood/water with Stephen Street, who did the Smiths' stuff. We were like, Oh my god, I can't believe we're here two months and living in this recording studio!

Why did the band break up?

Gosh. A hundred reasons. Mostly we'd just grown apart creatively, but also after doing it for eight years I think we just -- [He stops himself.] There's a point in any relationship where you're kind of like, Is this really what I want? We knew how to push each other's buttons and it had become an unhealthy thing. It was time for everyone to move on.

How did your coming out happen?

Someone from Spin asked me [if I was gay] and no one had asked me in an interview.

I'd read that there was some homophobic responses toward the band even before you came out.

We did this whole tour with Bad Religion that was completely miserable. There was one show in particular, somewhere like Iowa, where I think we stopped playing.

Do you have a sense of how your being gay affected the band?

I don't think it impacted us from a commercial standpoint. It probably had more of an effect on our personal relationships -- my happiness or unhappiness being projected onto everyone else. There were times when I was like, God, I'm living in the Midwest, playing in a touring band completely surrounded by hetero dudes. As a gay man, that's not very fun. I can totally relate to that [straight rock] stuff and do it all, but at some point, you're like, I'm not living a full life and how can I reconcile that? It took awhile.

Apparently the chat on your band's web site got so ugly following your coming out that your label replaced the entire message board with information about gay rights and anti-violence.

Yeah, yeah. That's true.

Was there anything positive about your coming out?

Yeah, definitely. One of the best things for me was that it made interviewers not ask ridiculous questions like, Who's your ideal girl?

Did you gain any gay fans after coming out?

Not that many! I thought, I'm going to get tons of dates now, it's going to be fantastic! I don't think I ever did! Actually, I did meet some people. Someone who became one of my best friends read that Spin article, saw me at a show, struck up a friendship, and I've now known him for eight years.

Do you think it's any easier for musicians to come out nowadays?

I definitely think so, but I still don't think it's that easy. I have a band that's just a hobby thing, House & Parish, and we went on tour in the fall. Everyone I'm touring with knows I'm gay. But just the day-to-day aspect of being in a band and dealing with road crews -- that's probably still pretty hard.

What's your perception of bands that really cozy up to sponsors? When we were a band, marketing didn't really exist for independent bands. If you were on a popular independent label, they might take an ad out or maybe they would pay for you to make a video. We made a living, but now the culture of music is completely different. Bands that don't even have a record out are hyperaware of the industry and marketing themselves on MySpace. That stuff really is in their hands. I'm sure there's still a really good punk scene happening that doesn't have anything to do with bands that are able to secure deals with Red Bull.

Do you have any feelings about bands like Fall Out Boy that wear the emo tag you had 10 years ago?

Being labeled punk or emo is neither here nor there. It changes with the time and with the scene it's living in. Whatever they're doing, if they're enjoying it, that's great. We're not curing cancer here, people. It's pop culture. At best, it can do things that propel politics forward or bring light to causes that people might not otherwise think about. But, at its worst, it's pretty harmless.

How do you feel about straight bands who have a gay aesthetic or who work a gay angle?

To me it's a little duplicitous. While I was figuring out that I was gay, I was in a hyper-liberal political punk scene and everyone was saying things to show how open minded they were. And I thought it wasn't fair because the people who really are gay don't feel like they have that luxury. [Pause] Do you mean people like Pete Wentz being on the cover of Out?

Yes. How do you feel about people like him drawing from gay culture, looking gay, and then influencing how young gay boys look?

I think that's totally fine and interesting. I think there's a big difference between that and people who are sort of playing gay. I don't really think that Pete Wentz being on the cover will mean that everyone's gonna think he's gay. Yes, some people will probably say that or whatever. But there's probably also a bunch of kids who will see that and it's no different than Queer Eye For the Straight Guy or Will & Grace. It's desensitizing people from being spooked by gays in Middle America, and that's great.

Was there anything intentionally gay about the artwork you designed for the band?

No... You mean the artwork for Nothing Feels Good, the weird rainbows of dots?

Well, those CDs are certainly brighter and more vibrant and happier-looking than a lot of other indie stuff from 10 years ago.

Yeah, maybe that's just the inherent Velvet Mafia aspect of culture. [Laughs] Why are gays trendsetters? Why are they artists, photographers, stylists, fashion designers? I guess it's just human nature.

Calling your band's EP Electric Pink and putting a big block of fuchsia on it is pretty gay.

[Laughs hard] I guess we were kind of rolling with it.

Did you study graphic design?

I actually never did. I got my education through doing it when I was in the band. I started our own covers, and spread into doing other people's stuff. Then when the band was over, it was a logical evolution to move here and just keep doing that. I've done record packages for bands like Counting Crows, illustrations for New York Magazine. I co-founded a design collective, Athletics, a few years ago.

What are you working on now?

Lots of stuff. I'm doing graphic design, a small clothing line of printed T's, and I think I'm opening a bar. It's something that a few friends and I have been kind of rolling around for a little while, but we found this space that already has a bar in it, so this week there's been a flurry of activity in trying to make the deal happen. It won't be a gay bar, but I think we're planning on at least having a gay night.

What's your gay life like now?

It's great. When the band broke up, it was for me a huge sigh of relief. I absolutely had to get out of the Midwest. It was just not a good place for me to be. Being here is great. I have a five-year relationship, I'm buying a house with my boyfriend, Jeff Madalena; he owns a clothing store, a small men's and women's boutique called Oak. We can't complain.

Send a letter to the editor about this article.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

41 male celebs who did full frontal scenes

September 16 2024 2:02 PM

39 LGBTQ+ celebs you can follow on OnlyFans

November 19 2024 9:39 AM

33 actors who showed bare ass in movies & TV shows

September 17 2024 5:43 PM

26 LGBTQ+ reality dating shows & where to watch them

December 10 2024 12:38 PM

21 times male celebrities had to come out as straight

November 19 2024 3:33 PM

17 queens who quit or retired from drag after 'RuPaul's Drag Race'

November 30 2024 12:26 AM

52 steamy celebrity Calvin Klein ads we'll always be thirsty for

August 27 2024 1:08 PM

15 things only bottoms understand

October 08 2024 5:18 PM

A gay adult film star's complete guide to bottoming

September 16 2024 8:50 AM

15 gay celebrity couples who make us believe in love

October 03 2024 5:43 PM

Latest Stories

A 2025 Guide to LGBTQ+ Spring TV

January 18 2025 12:53 PM

Trans comedians have advice for Dave Chappelle on SNL

January 18 2025 12:16 PM

What Alan Wore: 'The Traitors' references Easter Island

January 17 2025 8:06 PM

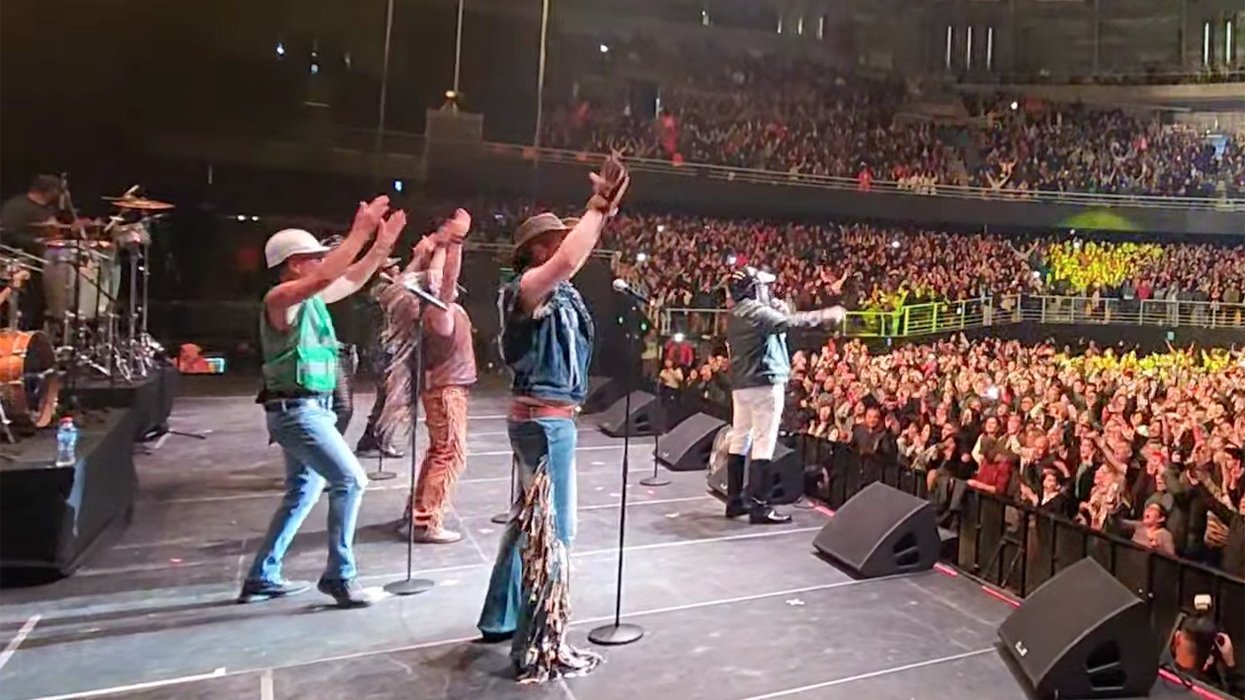

The Village People are now teaming up with Donald Trump—and here's why

January 17 2025 7:03 PM

'I Saw the TV Glow,' 'The Substance' lead LGBTQ+ critics' nods

January 17 2025 6:35 PM

Bob the Drag Queen reacts to 'Traitors' betrayal

January 17 2025 5:51 PM

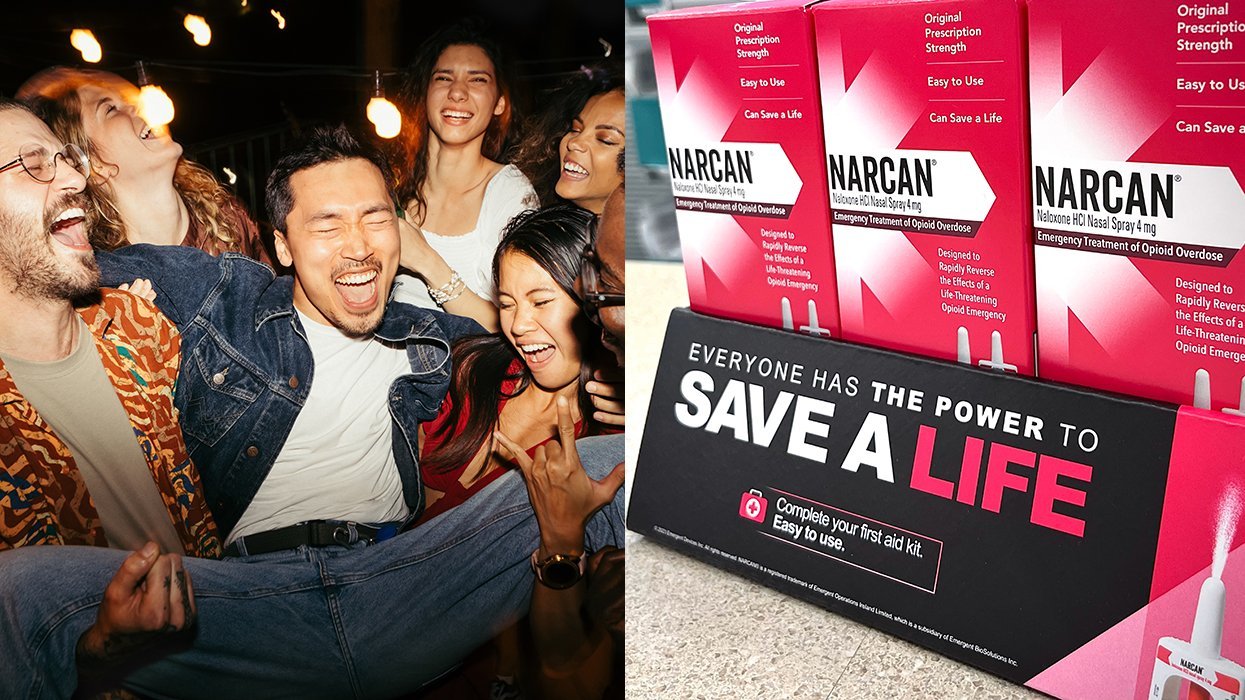

Want to save LGBTQ+ lives? Take a 5-minute Narcan training

January 17 2025 3:00 PM

Boxers NYC's 2025 calendar serves bulging bartenders in the buff

January 17 2025 2:13 PM

Nearly 3,000 LGBTQ+ advocates to join Tre'vell Anderson at Creating Change in Las Vegas

January 17 2025 12:50 PM

Kara Swisher says Mark Zuckerberg is a 'small little creature with a shriveled soul'

January 17 2025 11:21 AM

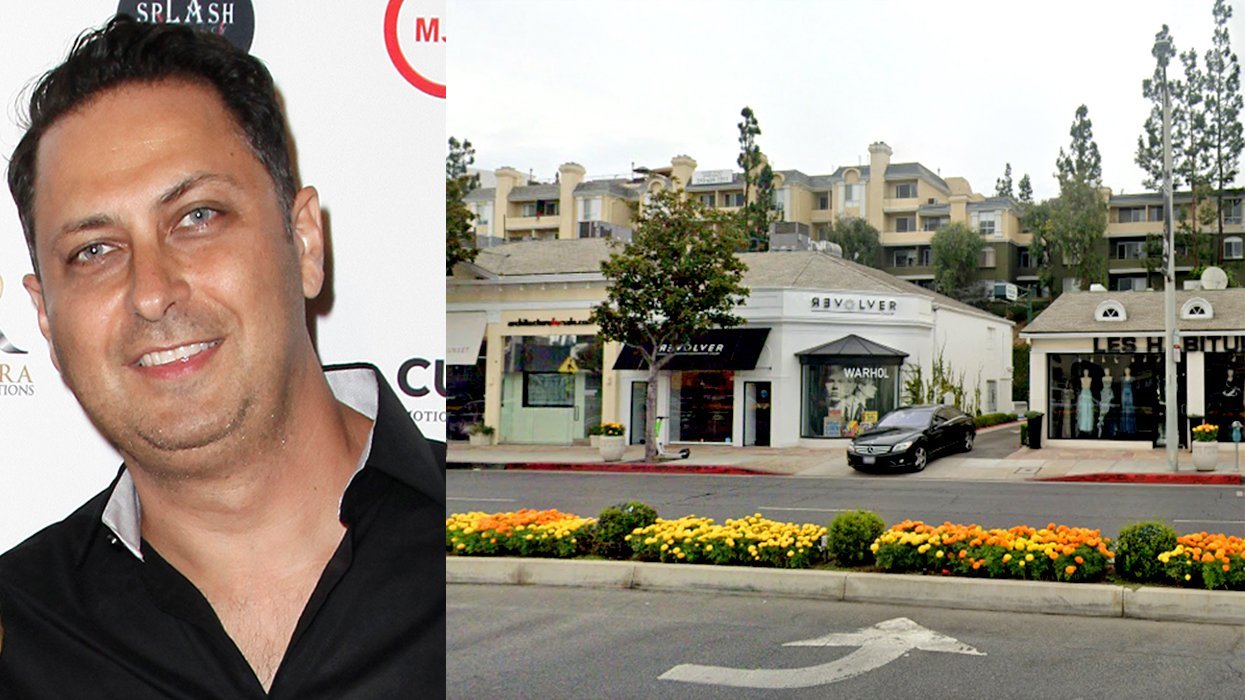

WeHo art collector says he lost Warhols, Harings in L.A. fires

January 17 2025 10:56 AM

The Traitors: Boston Rob's drag witch hunt of Bob may backfire

January 16 2025 9:11 PM

Open wide for these 69 sizzling Winter Party Festival 2024 pics

January 16 2025 6:30 PM

Anyma's epic Sphere residency and what it means for EDM

January 16 2025 6:05 PM

Trump's 2025 inauguration: Here's the full list of performers

January 16 2025 5:43 PM

Omar Apollo calls out 'homophobes' upset for posting 'Queer' nude scene

January 16 2025 5:07 PM

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays