Art & Books

Eternal Youth

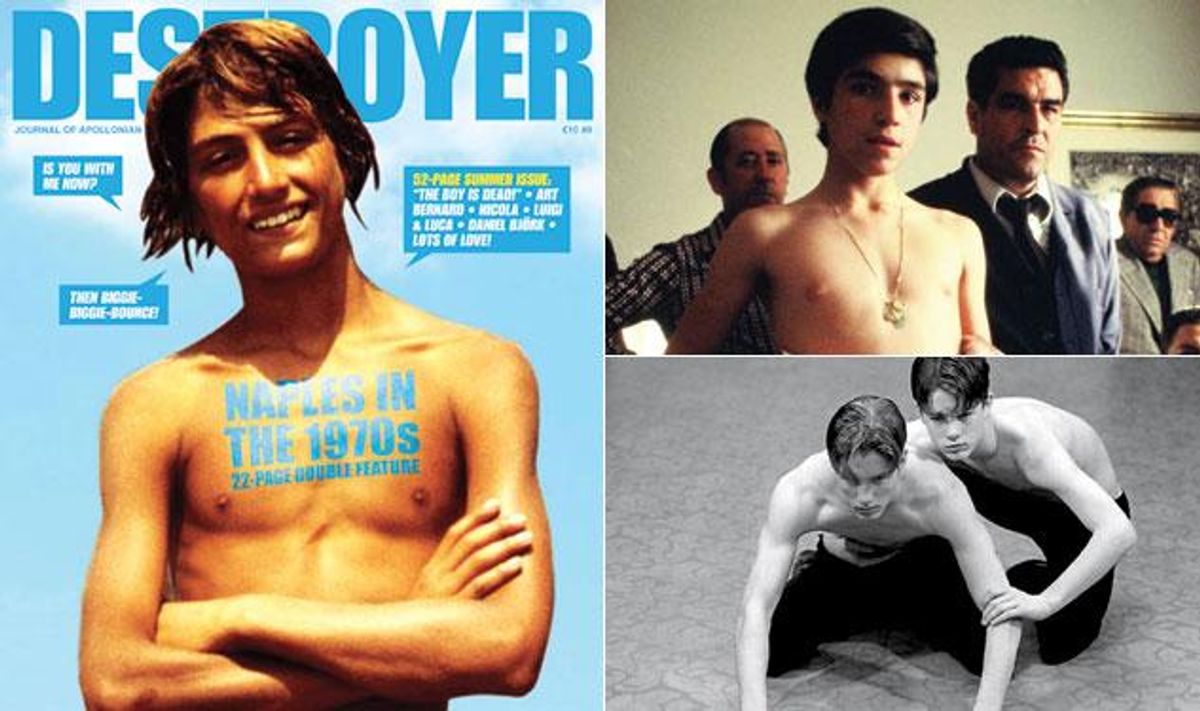

'Destroyer,' the controversial zine that objectified teen idols.

January 11 2012 8:55 AM EST

February 05 2015 9:27 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

For the final issue of his biannual zine Destroyer in 2010, provocateur-in-chief Karl Andersson proudly ran a compendium of comments about the publication that had appeared in the media. Included among the litany were: "This is filth!"; "This magazine sexualizes children!"; "It is really, really disgusting!" But these attacks were not from right-wing politicos--they appeared in the gay press.

"The most controversial expression of homosexuality is when a man is attracted to an adolescent boy," says Andersson. His magazine was billed as a "Journal of Apollonian Beauty and Dionysian Homosexuality," when, really, it was a paean to the love of boys--young boys, not just the twinks of today's homo-vernacular.

"The films that are called 'barely legal' feature men dressed as boys," says Andersson, 36. "I find it quite uninteresting. It's just drag. The models in Destroyer are well under 18."

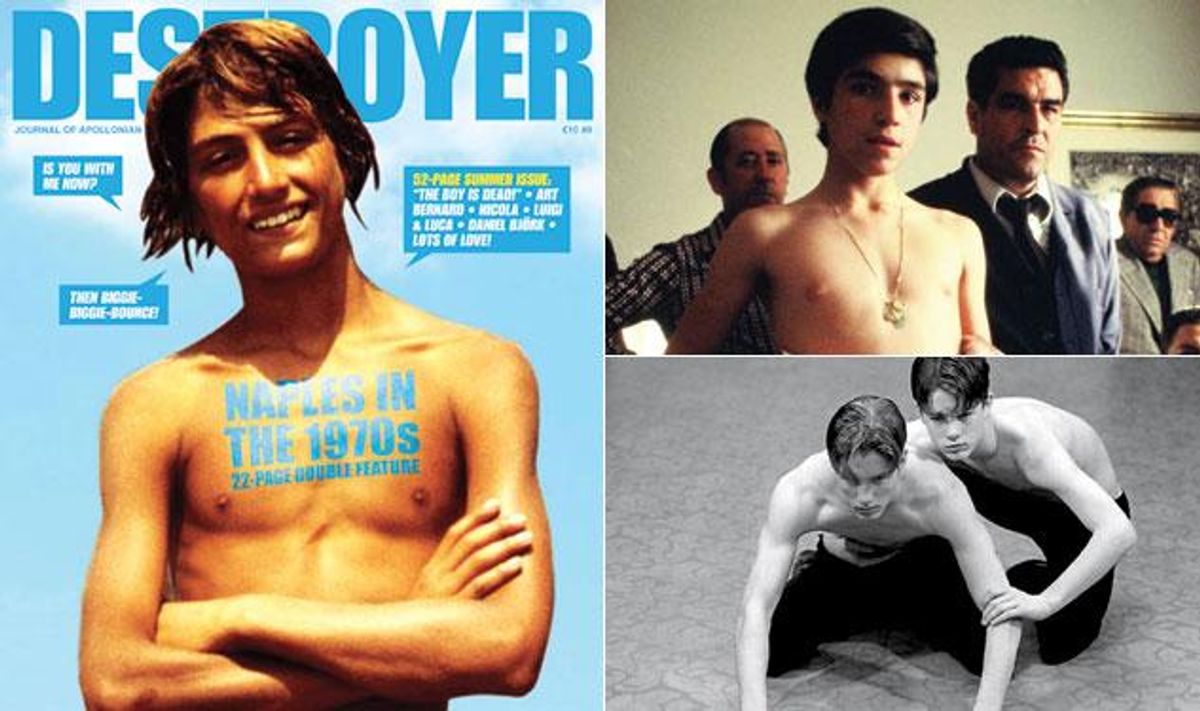

Started in 2006, each issue of Destroyer featured sexually suggestive shots of boys as young as 13 in various states of undress -- with an R-rating, rather than XXX. Many of the shoots took place in developing countries and sparked accusations of sexual tourism. In some images, it wasn't clear if the boys knew they were being shot -- Andersson equates this work to photojournalism.

"Can you take a photo of a person who doesn't know and publish it in a magazine?" he asks. "Legally, it is clear, but morally? Newspapers publish pictures of teenagers crying at a funeral when terrible crimes or accidents happen, and the photos are published on the front page. That's the same thing. Why is this criticism coming for Destroyer and not the newspapers? This is based on homophobia -- it's not OK for a man to find boys beautiful. Beauty is the strongest power that exists."

Destroyer sparked outrage in Andersson's native Sweden, known as one of the world's most open-minded countries, though of that reputation he says, "That was in the '70s!"

Probably due to its small circulation and import status, the magazine passed under America's moral radar. Nor was it controversial in Germany, where Andersson now lives. "It's more fun!" he says of Berlin, his adopted home city.

Andersson points out the double standard in a world where 13-year-old girls regularly strut fashion runways. "Society values boys more than girls," he says. "There is an instinct to protect the male offspring from being led astray by gay men. A feminist friend said, 'Why should we be upset about you objectifying boys when no one cares about the girls?' "

And objectifying boys is what Andersson liked doing best. "Destroyer was about making the models objects," he says. "I didn't want to know what they were thinking." Lines like "I'm Thin and Gorgeous!" were blazoned across the cover. "That's a reference to Absolutely Fabulous," Anderson says. "There are also references to Euro disco. Yes, it was a political pamphlet, but it was personal and I had fun doing it."

Andersson began his career in traditional journalism, helming Sweden's glossy gay magazine, Straight, and working at newspapers. He sees Destroyer as a link to a bygone era that was sacrificed as homosexuality became mainstream.

"The gay movement has lost touch with its past," he says. "It was founded to a large extent by men who were attracted to adolescent boys in Germany in the beginning of the 20th century. That should be acknowledged and it isn't. We should honor them because we owe them our freedoms -- instead, we despise them."

Andersson sells back-issues and PDFs of the mag on his website and recently self-published Gay Man's Worst Friend: The Story of DestroyerMagazine. The novella-sized memoir exhaustingly tells the story of creating the zine, from driving to the printing press to detailing each phone interview given to random European gay weeklies, and quotes (very liberally) from a student's university thesis that touched upon Destroyer. But the book doesn't reveal the stories behind the images, the lives of the boys (or of Andersson for that matter).

When asked about his own proclivities, he demurs. "In Destroyer, I took everything to its limit," he says. "The boys were supposed to be very young and sexually mature. I want to be secretive about my life. But of course, I can understand if, when someone sees Destroyer, they wonder if this is my private life."