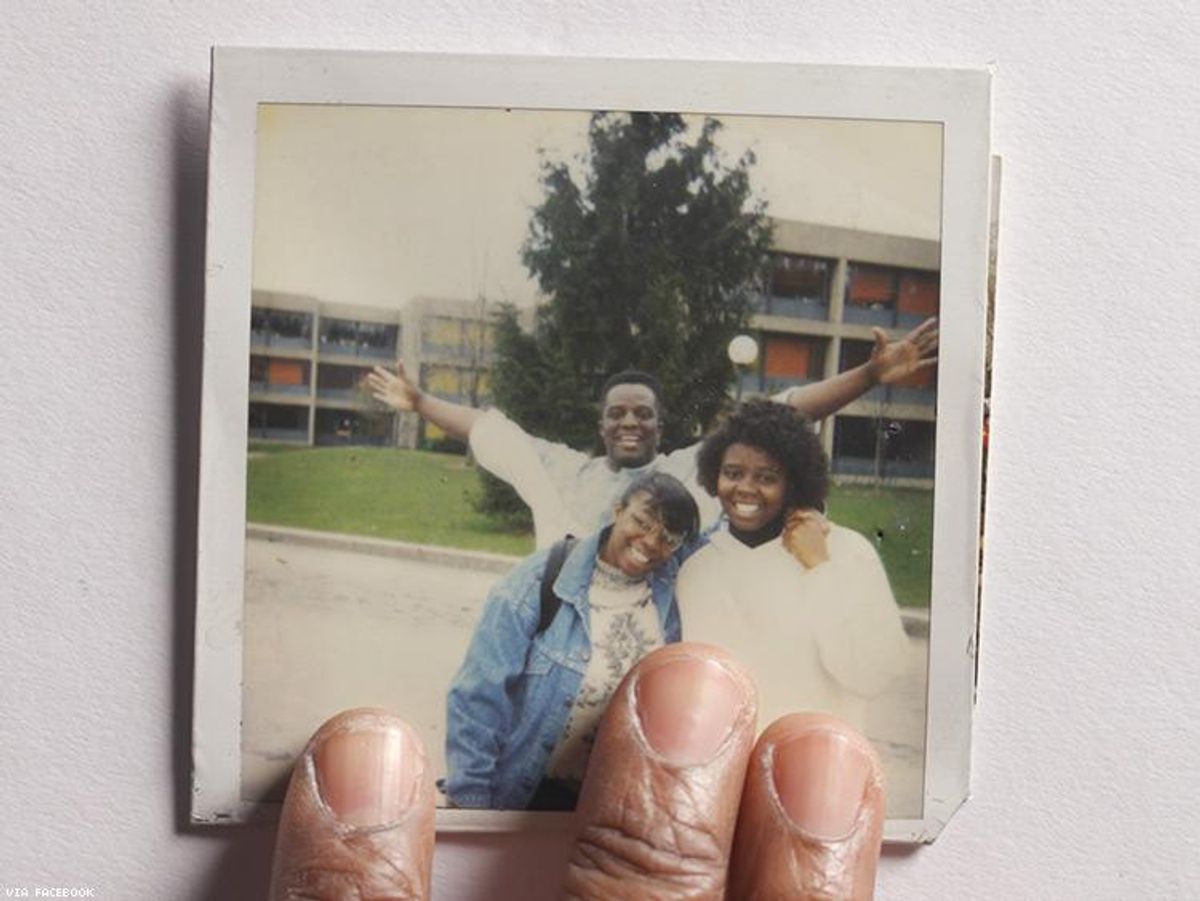

Director Yance Ford is largely stoic when narrating and appearing in his new film, Strong Island, making the rare moments when he emotionally cracks doubly devastating. This is the voice and face of a man whom society has forced into self-protective stillness--something to which any person of color can relate, especially if they've faced injustice from the law. Ford's documentary, which retraces the untried murder of his brother in 1992, is unique because it bluntly shows how that same stoicism infected an entire family. "It's meant to challenge how some audiences see black people," says Ford, "and to affirm the experience of those who've long said that race casts a pall over the criminal-justice system but have been dismissed." For Ford, whose experience as a trans person is both a footnote and a foundational element in his tapestry of grief (a pivotal phone call from his brother suggests he saw Ford's true self before dying), Strong Island is a call to arms: "I hope that in ending my family's silence, we challenge those who feel sorry for us to move beyond empathy into action."

OUT: Although this story is very personal, it strikes me as part of a growing wave of films striving to call out injustice surrounding wrongful deaths of people of color (Ava DuVernay's 13th comes to mind, as does David France's The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson). As both a filmmaker and a black American, what are your thoughts on the way cinema is currently addressing these topics?

Yance Ford: For decades, documentary films have chronicled the criminal justice system from all angles: unpunished murders, the barrier to full citizenship that comes with being labeled a "felon", innocent people sent to prison, heinous crimes that go unpunished... I could go on. We have reached a tipping point where the risks of making films like Strong Island and The Life and Death of Marsha P. Johnson and 13th outweigh the shame and silence that accompany the injustice--personal and institutional--that these films expose.

Strong Island is a layered meditation on grief--grieving the loss of your brother, grieving the loss of a family dynamic that will never be the same. What, for you, has been the hardest part of that grief, and how did making this movie help you come to terms with it?

When I began working on the film my brother had been dead for 15 years. His loss was a part of my life on a daily basis and making the film wasn't an attempt to comes to grips with his death or an act or catharsis. Strong Island is a portrait of grief over time and the failure to interrogate the fear behind self-defense shootings. The characters are eloquent when speaking about their grief. Their analysis of what happened during the investigation is brave and describes what has become a familiar pattern in deaths similar to my brother's. The critique of their experience with the criminal justice system is unflinchingly honest. When the audience grasps all that was lost as a consequence of my brother's death, [I believe] it is devastating.

Amid the drama of your family's narrative, you also had to grapple with your gender identity, which for many trans people would be drama enough. Did the hardships you had already faced in your life make it, perhaps, easier for you to find strength when assuming your identity as a trans man?

I have to be honest: I've been trans since the day I was born. I might not have had the word for it, but it's not new to me. The wonderful thing is that, though it was unspoken before he died, I realize that my brother could see me. The phone call in Strong Island--when he brags to me about standing up for my mother--is the type of call you would make to a younger brother. He called me. In that moment he recognized, as I say in the film, "the real me." I'm fortunate to have experienced that kind of affirmation from him. I don't think anyone was surprised when I came out as a dyke, and after years of being the best butch I could be, no one was surprised when I identified as trans. It was 1995 when I first saw the word "transgender" and that was hardest part: the gap between knowing and having the language to express what I knew. Making this film has oddly meant "coming out" again. But if my public presence helps one trans man, or helps break down the stereotype that black families are more homo- or transphobic than the rest of the galaxy, I'll be happy.

Roughly halfway through the film, you reveal certain things about your brother William, and his relationship with his murderer, that surely don't justify his killing, but deepen the preceding events. You make objective choices to present the whole truth, and in doing so, challenge the inherent racism of the average viewer. Please expand on this and discuss your choices on when and how to reveal information.

There are no perfect victims, period. It's a standard that we use as a society to justify unjustifiable acts of murder ("gay panic" is also a familiar perfect-victim trope). I made thousands of choices over the 10 years it took to make Strong Island. Being honest about my brother's interaction with the man who took his life was the easiest choice. William did not have a relationship with the man who killed him--he had an argument and he behaved badly. I am honest about that. These arguments happen hundreds of times a day in America. The difference is a black man could never use an argument like this to justify shooting someone three and a half weeks later. There is a simple litmus test here: reverse the race of my brother and the man who killed him. Do you think William would have been able to claim self-defense? Would a grand jury have decided that there was no probable cause to believe that a crime may have been committed? The transparency in the film is absolutely a challenge to some viewers who refuse to see that racialized fear justifies murder even when reason says otherwise.

If you had to sum it up in a few sentences, what were your main goals, artistically and otherwise, when creating this film?

I wanted to challenge the way some audiences see black people, who are often told that they are the ones who "make race an issue." The choice to put my mother in the center of the frame--in the center of her kitchen, even--was deliberate. We rarely see black women in this position of authority on screen. My mother is the expert on her own experience and the film doesn't use a white figure of authority to tell us she can be trusted. The audience has make a choice throughout the film: to look or look away; to listen or to get up and leave. I studied photography, sculpture, and performance art in college and I have a formalist's eye for composition and framing. Stillness and silence and observation are all used in Strong Island to invite the audience into an intimate story told by the people who lived it.

What do you feel are some of the greatest challenges facing marginalized communities right now, and how are you both discouraged and galvanized by them?

Traditionally marginalized communities are collapsing those margins and that is what makes me optimistic. Black Lives Matter. The Dreamers. People who have been most affected by the dysfunction of our criminal justice system. Trans women of color whose murders have never been a priority for law enforcement. From so many communities, ordinary people are refusing to let systemic problems be portrayed as personal failure. Strong Island is my contribution to that push-back.