"All the gays are going to die."

That's what Robin Campillo remembers newspapers--and nearly everyone else--saying in his native France at the dawn of the AIDS epidemic. It was 1982, the same year the director was pursuing his dream and attending film school. The photos Campillo saw in the press of people succumbing to the disease were intense enough to derail his plans. "Those images were so powerful, so impressive for me as a young gay, that they killed my desire to make films," he says. They also killed Campillo's desire to have sex, commencing a dry spell that would leave him celibate and rudderless for 10 years. It wasn't until 1992, when a lonely Campillo joined ACT UP Paris, that he found, in his words, relief. "We got stronger together," he says of the rebel advocacy group, modeled after the New York chapter of the same name, and composed of those infected and their allies. "We could create images that could change perceptions of the epidemic in society."

Campillo's new movie BPM (Beats Per Minute), which re-creates the filmmaker's ACT UP experience, isn't just a Cannes award winner that spotlights a historical, international queer moment--it's an artist's reckoning for time lost. Now 55, Campillo has been writing and directing films for 20 years (most notably 2008's The Class and 2013's Eastern Boys), but through much of that time, he's been aching to tackle the subject that both rocked and revived him. "I searched for years, but whenever I'd write a script about one person with AIDS or HIV, I'd decide against it," he says. "I eventually wanted to make a film about this political moment--not about being a victim of the epidemic, but about being stronger and becoming active."

Arnaud: Full Look by Alyx Studio

The result is a dynamic slice of stick-to-your-guns cinema. Clocking in at nearly two and a half hours, BPM risks modern viewer attention spans by delving into medical jargon and the potentially laborious strife of ACT UP Paris's in-house debates. It also disregards certain viewers' discomfort with the staging of a 12-minute sex scene, which comprehensively covers fear, intimacy, protected penetration, recollection of infection, and the valid, legitimate joy of the HIV-positive orgasm.

"No one told me, 'You should cut this film this way or that way,'" Campillo says. "I did the film I wanted to do, and I didn't try to please what we could call the others--in this case people outside the [queer community]."

Moreover, the director decided to mainly work with LGBT actors, claiming straight actors "didn't have the same experience," or at least lacked a lingering connection to the crisis.

Nahuel: Full Look by Yohji Yamamoto

To play Nathan, an ACT UP Paris newbie and essentially his own proxy, Campillo enlisted gay--and all-but-retired--actor Arnaud Valois. "I'm a Thai massage therapist now, and I hadn't acted in five years," says 33-year-old Valois. "But when the casting director told me about the subject, I said, 'Let's give it a try.' We'd never had a big AIDS movie in France--not one this political."

Valois was a child in ACT UP's heyday, and his memories of the group's actions are foggy, but he does recall such stunts as a giant pink condom being placed on Paris's Luxor Obelisk. "But that's less a memory of ACT UP than a memory of AIDS," Valois says. "For my generation, [the stunt] was just something else that explained that if you have sex, you use a condom. That's it. Safe sex all the time."

The notion of BPM doubling as a smelling salts for today's PrEP-emboldened, condom-averse youth was important for queer actor Nahuel Perez Biscayart, who drops trivia about current spikes in STDs like syphilis, and who had to interpret the nature of infection to play Sean, Nathan's fellow ACT UP member and HIV-positive lover. "Dying and withering was something I had to imagine inside myself," the 31-year-old says.

Robin: Pullover by Stella McCartney

Biscayart notes that Sean, whose waning health makes him the organization's most fervid and controversial member, is a distant cry from his own persona. And yet, while Campillo and Valois attest that BPM is an intrinsically queer movie--and not something the wider critical community can patronize as "universal"--Biscayart dissents. "When we released the film, 15-year-old girls and old ladies would come talk to us about it," he says. "I understood then that the film was very broad and that the LGBT-ness was not that important, because what was being expressed was so much more than that."

In their own ways, all three men have seen and felt the impact of BPM. Valois says he's received messages from young people who, inspired by the film, want to join community groups or are asking teachers about championing similar causes.

But it's Campillo who had the most poignant revelation as BPM hit French theaters. A scene in which Nathan tells Sean of an ex-lover he presumably lost to AIDS was directly lifted from Campillo's own story about his first boyfriend, who died one of a million secret deaths, far from Campillo's eyes. "Because of this film, I heard from my boyfriend's doctor," Campillo says. "And I'm going to see him, and learn about that last month of my boyfriend's life. In that way, the film has been a bottle

in the sea."

Photography: Laura Stevens

Styling: Benoit Guinot

Grooming: Oceane Sitbon Ghoula

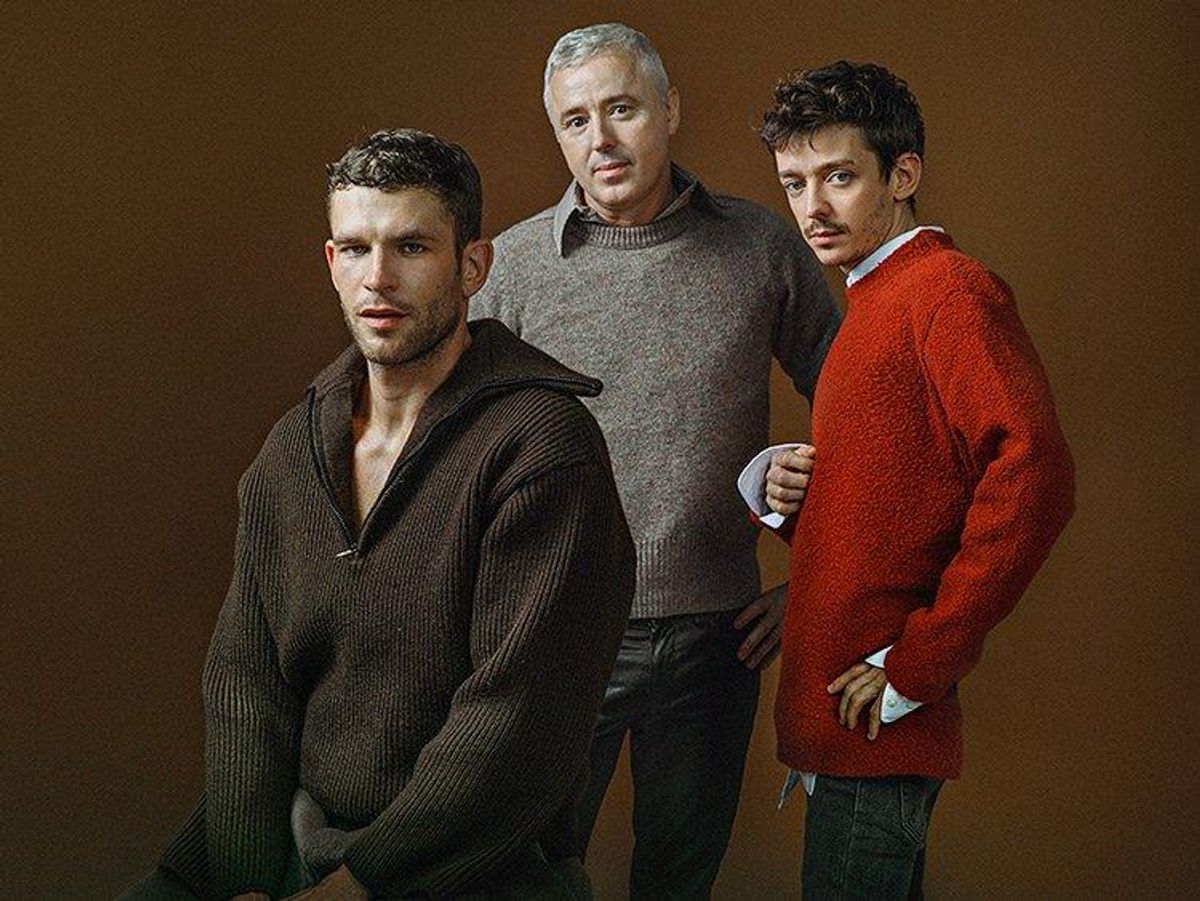

(Featured Photo) Arnaud: Full Look by Acne Studio; Robin: Pullover & Shirt by Acne Studio, Jeans by Drome; Nahuel: Pullover by Acne Studio, Shirt by Dries Van Noten