In the iconic film Paris Is Burning, about the thriving 1980s Harlem ballroom scene, young, gay men of color vogue on New York's dingy Christopher Street Pier in front of cement barriers tagged with graffiti and surrounded by trash. In the new documentary Kiki, young, queer people of color vogue near that same spot, only now it's landscaped with paved paths, ample lighting, and strollers -- the backyard of the swanky West Village. The contrast is striking, a metaphor for a community that has since attained a degree of acceptance and exposure.

It would be unfair to call Kiki a sequel to 1990's Paris Is Burning, but it's clearly a descendant. (Like its predecessor, Kiki premiered to acclaim at the Sundance Film Festival.) The film, which Sara Jordeno directed and co-wrote with Twiggy Pucci Garcon, follows seven members of New York's kiki scene (including Garcon) as they compete in balls, struggle with familial relationships, and navigate their sometimes shifting identities. A "community portrait" is how Garcon describes it.

Related | Vogue the House Down with Glorious New Ballroom Doc KIKI

"Our goal is for the world to know that ballroom has something to say, and that the world can really learn from this culture, this community that we created for ourselves," says Garcon, sitting in the midtown Manhattan offices of the True Colors Fund, an organization to tackle LGBT homelessness, of which he is an associate program director.

The kiki scene is a relatively new youth-led component of the larger ballroom scene; Youth accessing programming at the Gay Men's Health Crisis--which provides health and housing information and resources to communities disproportionately affected by homelessness, HIV, and AIDS--started it a dozen years ago, and staff involved in ballroom made it an intervention. Members typically "age out" of the kiki scene into the mainstream ballroom scene at the age of 24, though many stay involved and some perform in both scenes.

Related | The Ulimate Paris Is Burning Viewing Guide

Like Paris, Jordeno and Garcon's film seduces with stunning outfits, ferocious dance moves, throbbing music, and memorable subjects like Gia Marie Love, Chi Chi Mizrahi, and Kenneth "Symba McQueen" Soler-Rios. It also examines the personal hurdles and harsh realities these subjects have confronted. What's remarkable about Kiki, arriving nearly three decades after Paris, is how much things have changed (same-sex marriage, trans visibility, a spruced-up Christopher Street Pier) and also how much they have stayed the same for queer people of color, too many of whom remain victims of bigotry and violence.

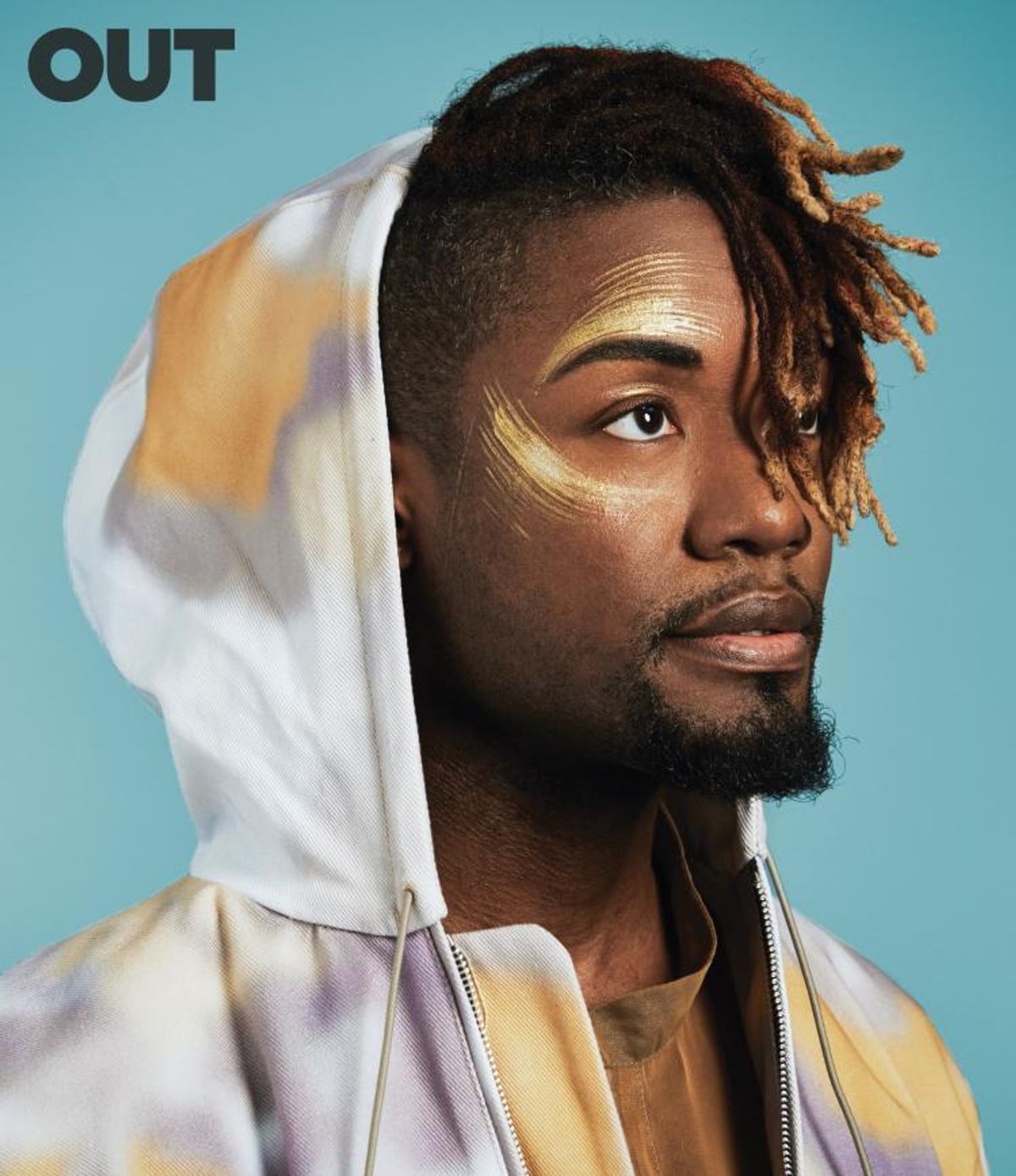

Suit: Moschino Couture

"This autonomous culture that's nearly a century old has managed to stay alive and well through the drug crisis, the HIV and AIDS crisis, and several presidential crises," says Garcon. "It continues to stand on its own as a safe, affirming space for people when they don't have anywhere else to go, to exist."

A noticeable difference between Paris and Kiki is the vocal, urgent activism depicted in the latter. The kiki generation "will not stop until they have real political power," says Jordeno, who'd worked in political, community-based art until she lost faith in activism. Making Kiki restored her faith. "It's activism and this amazing art form all at once," she says.

Related | New York Ballroom Culture Takes Center Stage in Qween Beat's KIKI Music Video

Jordeno and Garcon met in 2012 at FACES, an HIV and AIDS service organization in Harlem where

Garcon worked at the time. "Although we're vastly different, her being a woman from Sweden and me being a cis black man from Virginia, energetically we meshed really well," Garcon says. They'd both struggled with sexuality and religion: "We connected around a lot of the hardest parts of our lives."

Following the success of Paris, that film's director, Jennie Livingston, faced criticism from the ballroom community for telling a story about them, rather than with them. Kiki's creators made a conscious decision to produce a collaborative film. "I was welcomed because they saw very quickly that I was not going to come in, film, and leave," Jordeno says. "I was in it for the long haul."

Now, after four years of filming, Kiki will open in theaters this spring -- a feat that has brought Garcon peace. "Creating this film helped me heal and come to terms with a bunch of different things," says Garcon. "My relationship with my father, my relationship with my mother, who and how I am in the world. How I show up."

Photography: Daniel Seung Lee

Styling: Michael Cook

Groomer: Angela DiCarlo

Photographed at Tribeca Journal Studio in New York

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.