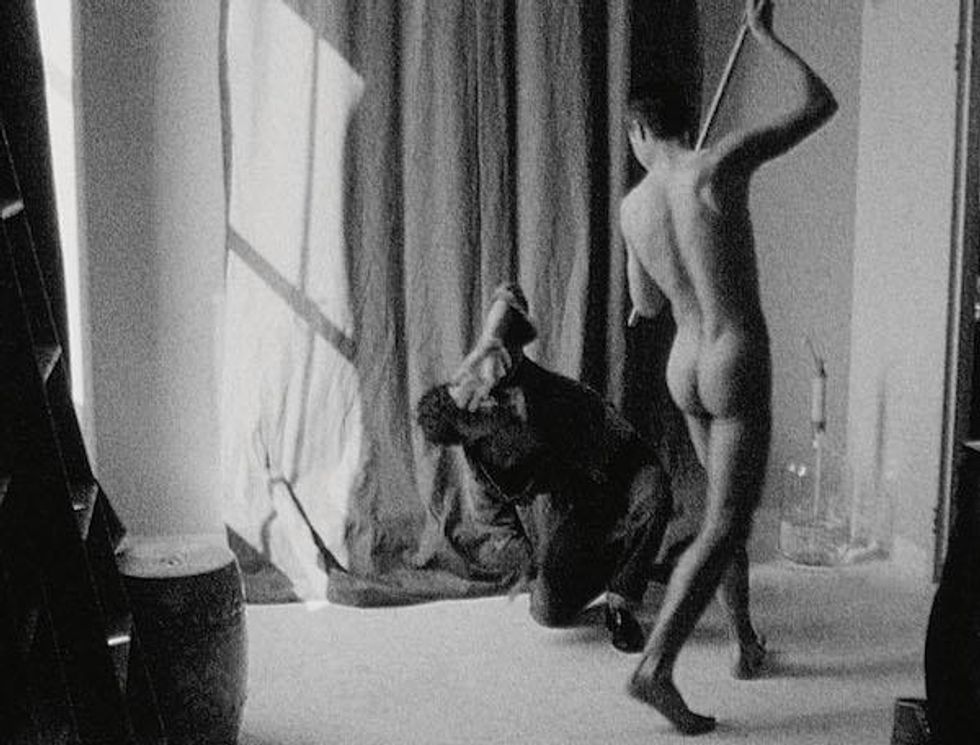

Pictured: Punk icon Jordan dances in a tutu in "Jordan's Dance" | (c) 2014 LUMA Foundation

With over 700 stills from the Super 8 short films created by Derek Jarman, Derek Jarman Super 8 exemplifies why he's one of the most influential filmmakers of the 20th century. He transcended the avant-garde to make cult feature films such as Jubilee (1978), Caravaggio (1986), and The Last of England (1988). Not only was he a painter before venturing into the world of film, his painter's mentality permeates all his work, particularly his experiments in Super 8 film. James Mackay has spent the last 20 years archiving, restoring, and digitizing the Super 8 films. In this volume, Mackay presents stills from these works -- including In the Shadow of the Sun (1972-74), My Very Beautiful Movie (1974), Gerald's Film (1975), Art & the Pose (1977), Waiting for Waiting for Godot (1982), and Pirate Tape (1982) -- selected by artists and filmmakers who have engaged with or been influenced by Jarman.

As Mackey notes: "The earlier works, all shot with a tripod, have an overwhelming sense of people and objects placed in front of the camera, composed as they would be for a painting." Captured in this volume (available now from Thames & Hudson), the images are accompanied by illuminating commentary by Gina Birch, Liam Gillick, Isaac Julien, Sarah Turner, and others. To help explain the significance of this collectable, we have an exclusive excerpt between Beatrix Ruf and James Mackay below.

RELATED | DEREK JARMAN'S ART CONVERSATION

Beatrix Ruf: You said that [Derek Jarman] was very professional in his approach and that the Super 8s were not only about experimentation. Were they kind of an ongoing sketchbook?

James Mackay: In one sense, yes, because he was free to experiment, and quite clearly he learned from film to film. In another way, no, since the effort he invested made many of them far more than mere sketches. Some are constructed from many superimposed layers, achieved over time as each layer is filmed, refilmed, and filmed again. And he considered In the Shadow of the Sun to be just as important as any of the feature films that he made in the 1970s: Sebastiane, Jubilee or The Tempest.

He couldn't understand why the critics didn't see them as being of equal worth. He was genuinely baffled. Much later on, when he was making Edward II, he told me that he thought he'd got the balance right and had bought 35mm closer to the Super 8 way of working. He was always conscious about the two different types of filmmaking. And he was always trying to imbue 35mm with the flexibility and ideas of Super 8.

BR: Quite a few of the Super 8s were transferred to 16mm, and you were involved with that.

JM: A few, in the early 1980s. With the help of the Berlin Film Festival we transferred In the Shadow of the Sun to 16mm. We also had four other films blown up from Super 8 to 16mm. At the time I met Derek, he'd already curtailed showing the original Super 8s because they were getting worn and he was scared they would be damaged. That's why we raised money: to have them blown up to 16mm so that he could show them but preserve the originals.

Derek was really proud of his Super 8 work. It was very important to him. He told me he put as much of himself into a film like In the Shadow of the Sun as he did into The Tempest.

BR: Was he interested in showing them in an art context or as this "stream of images" we talked about earlier?

JM: Both, really. I've just remembered that in the second year I knew Derek, he arranged for the Super 8s to be screened at an art fair at the Barbican, London. This was 1981. I went along, and Derek had arranged for a booth like they have at art fairs, equipped with a tape player and monitor. I had a video copy of In the Shadow of the Sun, and I showed the film. And nobody was interested! Derek didn't come, of course.

Jean-Marc Prouveur and Gerald Incandela pose as George and the Dragon for Derek's camera (1977)

BR: Did you stop screening the 1970s Super 8s?

JM: Yes, Derek's last real screenings were in 1979-80. To transfer them to 16mm would have been very expensive, and we were both really broke. Derek was living a fairly hand-to-mouth existence then because making a feature film in the 1970s didn't pay very much. Cans of soup. Most people were broke. But as we got into the 19080s Olympus brought out a Portapak, a VHS camera. Derek managed to persuade them to lend him one. And so he started to use that to transfer films to video.

BR: By refilming Super 8s projected on the wall?

JM: On a sheet of white card taped to the wall. We spent three days in 1982 at the ICA, refilming some of Derek's Super 8s onto video using that camera. On the second day we got bored and started filming other things. Derek projected films onto the guy who was helping us and refilmed them with that camera; that ended up as the central part of Angelic Conversation, the guy holding the mirror.

Then, when Derek returned from a Russian tour, we used the resulting black-and-white Super 8 footage to make Imagining October. Once finished, those two films were shown in Berlin, and Dagmar Benke from ZDF, the German broadcaster, approached us and said she'd like to fund a film, so we made The Last of England. At that point we forgot about transferring the Super 8s and concentrated on making new films.

BR: But he was making Super 8s the whole time, yes?

JM: He made and edited Super 8s up until 1982, 83, After that, they're all part of something else: shorts, features, music promos. They're not standalone films edited to be Super 8 films.

BR: And he never continued that attitude of experimentation and filming as a sketchbook with video?

JM: Yes, he did. I have some videotapes, two of which are transferred to DigiBeta, and some others in a box that I haven't played because I'm worried they'll get damaged. The two films that I've seen are just continuous takes: they're rather good, actually, they're fun. He doesn't film in the same way that he filmed with Super 8, because he's using sound and talking to people.

BR: You mentioned once that Glitterbug was supposed to be the image-loaded counterpart to Blue.

JM: You're right. He discussed it with me first in 1987, around the time we were finishing The Last of England. Already he was talking about two films: Blue, and a companion piece made of images from his Super 8s. However, by the time we got to the end of Blue he was very ill. Nigel Finch and the BBC stepped in very kindly and gave Derek a slot on Arena, the arts program, to make a compilation of his Super 8s. It had to be 54 minutes, so it's much shorter than Blue. Transferring so much quickly to video was very difficult, so we concentrated on the more documentary aspects of the Super 8 work, the recordings of people and places. It wasn't really quite the film he intended as a companion piece to Blue.

BR: I understand that he was very sick then, and almost couldn't see any more.

JM: He was very visually impaired and his health wavered. The great thing about Telecine, about the professional copying of film to video, is that you view it on a very bright screen, so he was able to see the images quite clearly. He could completely recall every single frame of film. As we went through the transfer he would tell us where and when it was filmed, who was in it, which images were coming up next. If you think about it, there were 82 films, plus the diary films -- that's a lot to remember. he had a remarkably strong visual memory, Derek.

BR: So Glitterbug marked the beginning of your work with the archive?

JM: Yes. It was constrained by a small TV budget, but it was the beginning of the archiving process. We looked at quite a lot of the Super 8 material, but not all of it. There was too much.

SLIDESHOW | IMAGES FROM DEREK JARMAN'S SUPER 8 ARCHIVE

BR: What was Derek's intention in giving the Super 8 archive to you?

JM: I met Derek because of the Super 8s, and I think I was one of the few people who took Super 8 film seriously. I got told off by some of the more senior filmmakers at the Co-Op for showing Super 8: they said serious filmmakers make 16mm films. But my contemporaries were all working with Super 8 and I suppose he thought I was somebody who would take good care of it.

BR: In the 1990s, many young artists started using 16mm once more, even Super 8, attracted by the image quality and its materiality. Did you ever consider copying the Super 8s to film stock to make them accessible in an art context?

JM: Derek's a famous filmmaker now, but although he was critically acclaimed, when he was alive they weren't throwing money at him. The budgets were tiny, and the mechanics of filmmaking are always expensive. As for the materiality of film, it's sometimes fetishized by artists. It would be possible, thanks to the conservation project, to make superior film prints, such as digital intermediates, which are now standard practice in the industry. Projecting Super 8 as Super 8 is a poor option, because the projectors are not very good.

BR: And now that the conservation project is finished, how do you see the archive functioning in the wider world?

JM: Well, I see it as a complete archive of work accessible to viewers, artists, students, curators, and writers. It can be shown to the public in different ways. The important thing is that now every single frame is accessible, which I think is unique in an artist's film work.

BR: I imagine there's a lot that has never been seen?

JM:Derek sometimes ran short of film spool, so in order to free up space he would wind one film on top of another. So I found a few films that I had never seen or didn't know existed. He kept all the fragments, he didn't throw anything away. He just assembled them into the dozen reels he called It Happened by Chance. So there are all the little bits, the failed experiments, the snatches of his domestic life or what's happening on the street outside his window.

BR: This brings us back to how interpretation and presentation define a work. A crucial element of the archive is that the knowledge of how things came to life is part of that archive too. How have you integrated your personal knowledge and experience into it?

JM: There's another small phase of the archive work that I still have to do. I'm going to interview all the available people who took part in the films and get a verbal record of that time, and of how the films were made.

Derek Jarman Super 8 is available now

Excerpted from Derek Jarman Super 8, by James Mackay (c)2014 James Mackay and Thames & Hudson Ltd, London. Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc.

SLIDESHOW | IMAGES FROM THE DEREK JARMAN SUPER 8 ARCHIVE