Interviews

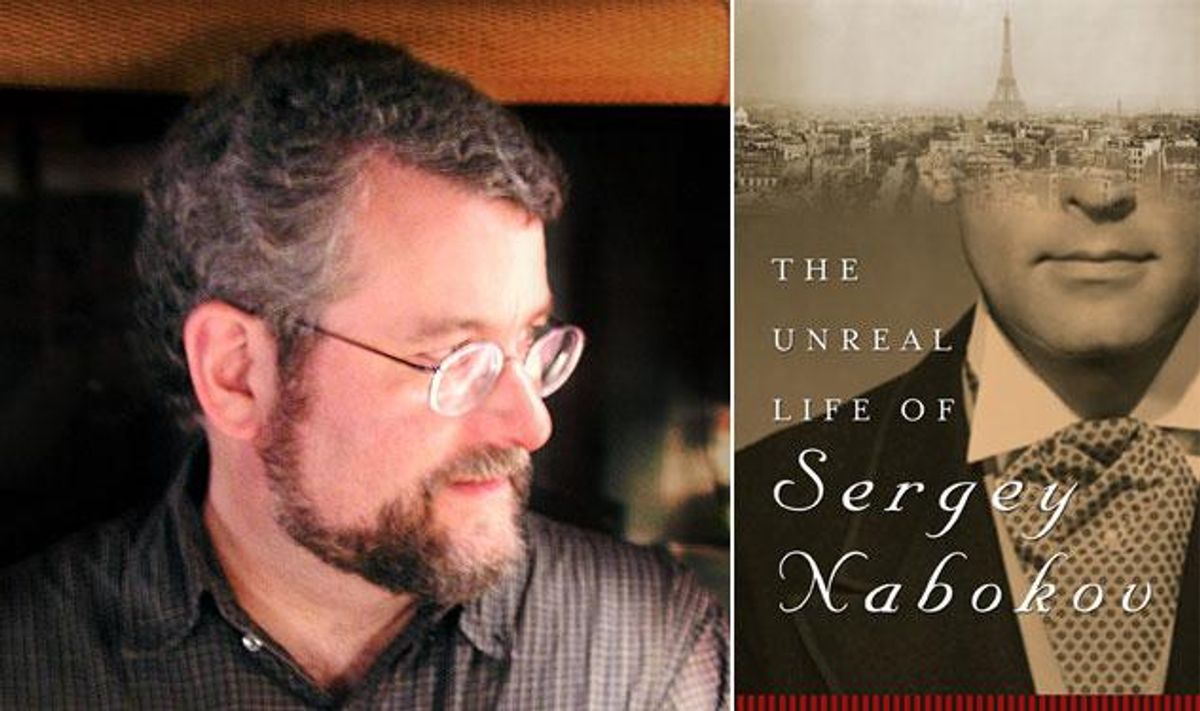

Interview: Paul Russell, Author of "The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov"

The author describes reconstructing the lost life of Sergey, the gay Nabokov.

January 10 2012 12:29 PM EST

February 10 2019 9:50 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The author describes reconstructing the lost life of Sergey, the gay Nabokov.

The world has only really known one Nabokov: Vladimir, the Russian emigre who wrote Lolita, Pale Fire, and Pnin, to name just a few works from a prolific career. Known for producing characters of all persuasions (from mad men to pedophiles) the acclaimed author concealed one real-life character for decades: his gay younger brother, Sergey. It was only in the third edition of his autobiography, Speak, Memory, that Nabokov delivers an account of this sibling, and then he does so hesitantly. "For various reasons, I find it inordinately hard to speak about my other brother," he writes.

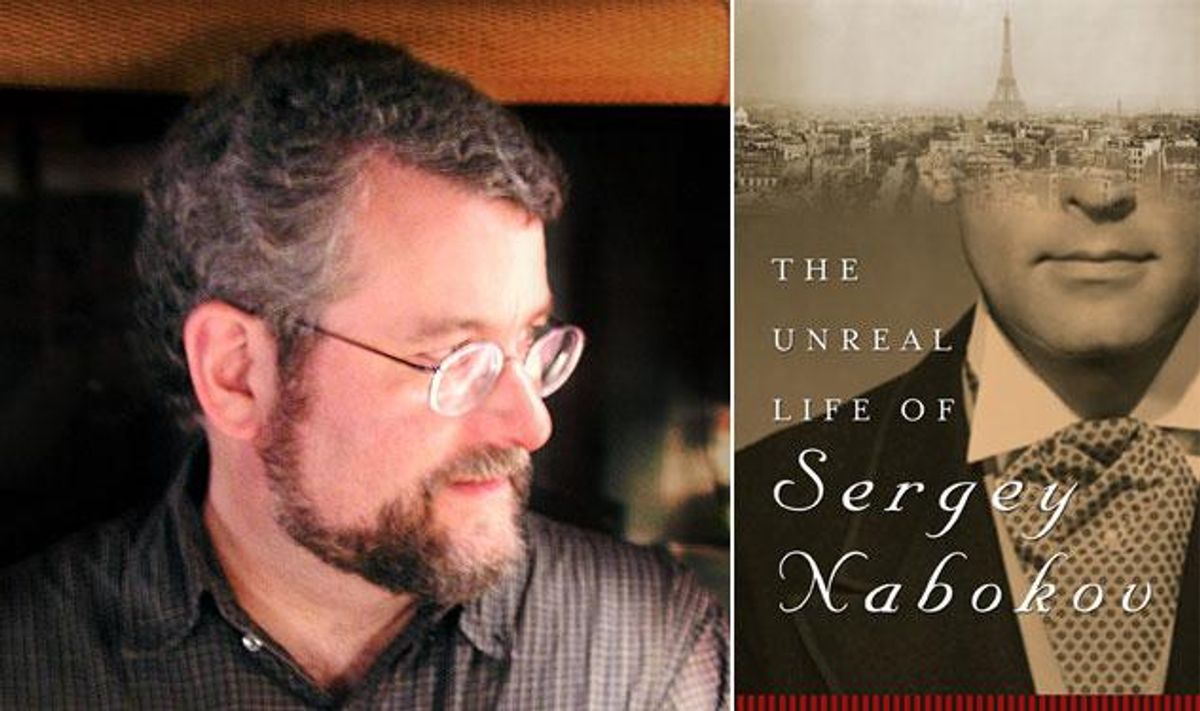

In his latest novel, The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov, Paul Russell (author of The Salt Point and The Coming Storm) finally gives voice to this eclipsed Nabokov. In a narrative that spans from Czarist Russia to the Parisian Modernist milieu to the crumbling Nazi regime, readers follow this amiable young man as he flees the ruins of his aristocratic upbringing and creates a new life for himself. Carefully researched and richly detailed, the book presents a captivating portrait of gay culture in the first half of the 20th century.

In anticipation of his reading at Word bookstore in Brooklyn on Thursday, January 12, Out spoke with Russell about uncovering the gay Nabokov and recreating the lost worlds in which he moved.

You mention Lev Grossman's article in 2000, "The Gay Nabokov," inspired your book. What was the process from there? I'd known of Sergey's existence from the scant evidence Vladimir Nabokov eventually included in the third version of his autobiography Speak, Memory, but it wasn't till Lev's article that I was able to imagine him as a character. I spent a year researching; I read histories, diaries, biographies from the period (rather a sweeping period at that, from Czarist Russia through Paris in the 20s and 30s to a castle in Austria to wartime Berlin).

How blank a canvas was Sergey's life, and how comfortable were you filling in those spaces? Lev's article gave me the spine of Sergey's life; most everything else, I had to invent, often drawing on the barest of suggestions. In my novel, for instance, Sergey becomes an opium addict. I have no hard evidence of that: only that Vladimir's biographer Brian Boyd reports that, when the brothers met in 1932, after a hiatus of some years, Vladimir described Sergey in a letter to his wife Vera as "glassy-eyed, somehow tragic." Since I know that Cocteau, with whom Sergey was friends, had a habit of introducing his enfants to opium, I made the imaginative leap. I'm sure I've gotten all sorts of facts completely wrong about Sergey, but I hope I've captured a larger truth about his life.

The Unreal Life paints the early 20th century as an exciting time to be a homosexual - drag balls in Russia, Hirschfield's Scientific Humanitarian Committee - only to have that shattered under Nazi rule. How would you say gay culture was different then? What's interesting to me is how open gay life was, at least in the cities. It was an open secret, in that straight society turned a blind eye. Lots of stuff went on in the open, and no one noticed or registered what they were seeing. That's the big difference between then and now, I think. Now we register everything. We're hysterically aware of gayness. There's constant surveillance. We're both more liberated and more policed than we've ever been.

Sergey has a directionless quality - Alice B. Toklas calls him "an unknown young man of inscrutable intent." What's it like writing someone that plays like a supporting character in his own novel? I wonder how many of us feel like a supporting character in our own novel. I certainly do at times. I mostly thought of Sergey as an ordinary mortal wandering among sacred monsters. The monsters will steal the scene every time, and that's what they proceed to do. But I hope, in the end, there's something to be said for Sergey's translucent modesty.

Sergey's journey through Europe hits on a lot of important periods in gay history: Hirschfield's attempt to repeal Paragraph 175, homosexual dalliances in Cambridge, Cocteau's Modernist coterie - is it likely Sergey was involved in so many circles? It does sometimes seem that Sergey is hitting an impossible number of historical and cultural highlights, but that's part of his life that I'm not making up. He really did know all those people. The world was smaller then (by several billion people!), and it was possible, in Paris in the 20s, to be in the thick of everything in a way that's just impossible today.

What are your thoughts on Vladimir Nabokov's homophobia? Vladimir's homophobia is the elephant in the room of Nabokov scholarship. It's there, and it runs deep. But it's also more complicated than you might think. Insofar as Vladimir may have been abused by his uncle Ruka (and Ruka's fondling of Vladmir, as reported in Speak, Memory, bears uncanny resemblance to Humbert's fondling of Lolita), there were plenty of reasons for him to be skittish around homosexuals. But Nabokov's imagination finds its way to strange, surprising places. In some ways, the most revealing light Nabokov casts on his relationship with Sergey is in his short story "Scenes from the Life of a Double Monster," originally the first chapter of an aborted novel about Siamese twins. The things you fear most are the things that touch you most closely.

What can we expect at your reading on the 12th? Magic tricks, dancing boys, pyrotechnic mishaps, cigar-smoking squirrel monkeys, half-forgotten tunes hummed slightly off-key. The usual stuff that happens when a shy and retiring writer suddenly finds himself in the public eye. Plus my excellent and esteemed fellow novelist Christopher Bram will be there, attempting to engage me in intelligent conversation. Readers should check out his forthcoming nonfiction book, Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America.

Paul Russell will be reading at Word bookstore, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn on Thursday, January 12 at 7pm. You can read more about Russell and his other works at paul-russell.org.