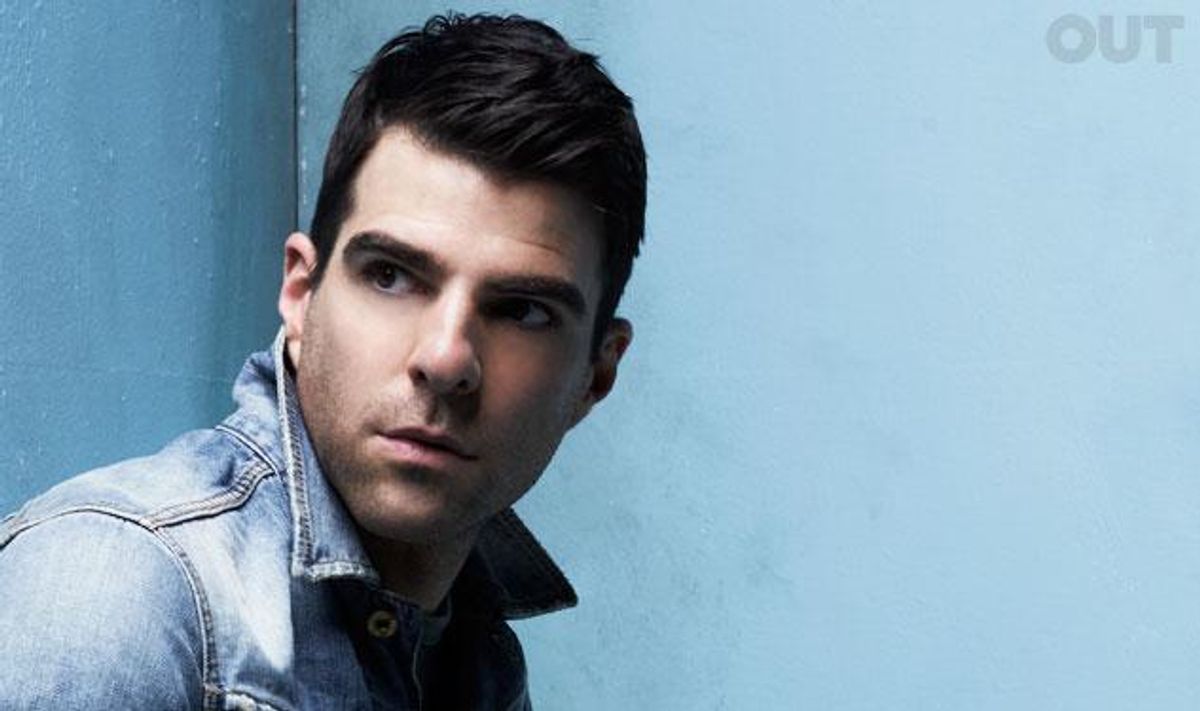

Photography by Michael Muller

Styling by Grant Woolhead

With a celebrity who has come out as gay, there's always a little verbal dance you do as you approach the subject you're most interested in. You talk about childhood, perhaps you talk about religion, and then gently, anxious not to appear crass, wary of being reductive, you start dropping small hints that grow gradually broader. On good days, if you're lucky and maybe just a little charming, they'll invite you to push further.

Zachary Quinto, however, is so immediately candid, so disarmingly relaxed, it's clear from the outset that we can dispense with the formalities. We are sitting in the yard of the small mid-century bungalow in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, that serves as the office of his production company, as his two dogs, Skunk and Noah, snuffle around our feet. Quinto has been talking about doing more theater, and is in the midst of extolling the genius of John Cameron Mitchell's East German transgender singer, Hedwig -- a role he has a burning ambition to play on stage -- when I feel compelled to interrupt.

"That's surprising to me," I say.

"Why are you surprised by that?"

"Because Hedwig is so unequivocally queer in its sensibilities, not just gay."

"I love that about it -- it spoke to that part of me, that queer part of me that doesn't always have the chance to express or reveal itself," he replies. "That's what excites me as an artist."

It's at this point, with the evening sun filtering through the overhanging branches of a lime tree, that I realize we have crossed a threshold. It is one thing to have celebrities acknowledging their sexuality, quite another to hear them talking about their inner queer.

Last October, Quinto negotiated the first of those steps in an interview for New York magazine, casually prefacing his response to a question about the revival of Angels in America with the words, "As a gay man..." In fact, he said it twice, just to make sure the point got through. It did, of course -- New York is not too urbane to appreciate a scoop, though what's fascinating about the way celebrities now come out in the media is how unscoop-y the whole thing must be treated. We have, blessedly, moved on from "Yes, I'm Gay!", or, even, "Yep, I'm Gay." The headline in New York was simply, "What's Up, Spock?" For Quinto, it wasn't even about coming out -- he'd done that with his family at the age of 24. "I thought about it as coming out from behind the wall," he says. "Walls now are only as high or as thick or as strong as we allow them to be."

Of course, it looked easier to scale that wall in print than it must have seemed in person, and Quinto admits to staying up until 5 a.m. the night before trying to figure it out. He gave no warning to his publicist or friends or family -- his performance was not screen-tested in advance. He just knew it was the right time to confirm what many people already believed, but on his terms, in his words.

Does he regret not taking the opportunity to set the record straight in a 2010 New York Times interview, when he deflected a reporter by saying he wasn't interested in discussing his sleeping arrangements? "No, not at all, absolutely not, because I wouldn't have initiated it," he says. "I knew very fundamentally, inside, that it had to be initiated and executed by me, and me alone." This turns out to be something of a recurring theme: generating initiative, being prepared, taking control -- in short, owning it. When he came out to his mother, it was from a similar sense of imperative.

SLIDESHOW: EXCLUSIVE IMAGES OF ZACHARY QUINTO

"I needed it to happen," he says. "Otherwise, I couldn't move forward authentically. Ultimately, I think the only thing that really drives me in life, continually, is a pursuit of authenticity of experience -- of myself."

Quinto is supremely self-aware, perhaps as a result of losing his father to cancer at the age of seven and having to renegotiate his relationship to the world. Although he describes his childhood fondly, in idyllic terms -- "running around in the woods, and playing on my bike, setting out on adventures" -- it's clear that his father's death threw his world off balance. "As well-intentioned as my family was, and our immediate friends, I don't think anyone knew how to talk to a seven-year-old at that time," he says. "My mother was, understandably, eviscerated, and my brother, who was 14, was impacted in a very different way, because he was at the pinnacle of fishing trips and camping trips with my dad."

It may also have been the moment when Quinto, who had grown up an archetypal Catholic kid -- an altar boy, choir boy, all-round goody two-shoes -- began to shift his devotion from the church to the theater. He recalls learning to mimic people as a way of learning how to respond to his father's death. A few years later, in fourth grade -- when he was getting his first inkling that he might be gay, "a little awareness that I staved off at the time" -- his music teacher, Miss Smith, sent him home with a note for his mom. It contained a newspaper clipping promoting auditions for a performance group associated with Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera. "It was like a singing and dancing group for kids, so my mom, looking for an outlet for me, was, like, 'Let's see,' and I was, like, 'I want to do it,' " he says.

At the audition -- "comprised of kids who had done, like, every production of Oliver! in a professional theater in Pittsburgh" -- he sang "America the Beautiful." "I think they were so gob-smacked that I was so clueless," he says. "They were, like, 'Great job, do you want to come back and do a song from Broadway next week?' " Quinto returned, sang "Consider Yourself," and scored the part of a munchkin in that summer's Civic Light Opera production of The Wizard of Oz.

From Munchkin to Vulcan is a long journey, and there were times when Quinto wasn't sure he would find the breaks to match the scale of his ambition. He remembers hitting 27 and feeling his certainties fall away. An amateur astrologer, he attributes his crisis of self-doubt to the return of Saturn, a harbinger of change and disruption, but says it was likely compounded by his tendency to mistake impatience for ambition.

"I had gone without working in years, and I was really, just, down," he says. A role as a gay Iranian-American in Tori Spelling's So NoTORIous showed promise, but the series was cancelled after 10 episodes. Then, as he approached his 30th birthday, several things happened in quick succession: he got a call-back for a role on a new NBC show, Heroes, that was blowing up; and, days after his 30th birthday, he scored a career-defining role as Spock in J. J.Abrams's Star Trek reboot.

For millions of Americans, Quinto was being entrusted with one of sci-fi's most cherished icons. He didn't let them down. Quinto's performance as Spock was pitch-perfect, almost uncanny, with unexpected grace notes of fallibility. A global smash for Paramount, Star Trek gave new life to the 40-year-old franchise and propelled Quinto into the first rank of celebrity. A highly anticipated sequel, set to open next May, wrapped this summer. Quinto says the new movie is more physically challenging than the last, although one suspects that Spock's stunted emotional range could feel limiting for an actor of Quinto's expressiveness.

"Tell me about it, man," he sighs. "Whereas other actors will be doing scenes, and will be given, like, 25 takes, after I do five takes with that character, it's, 'OK.' " He claps his hands with finality.

SLIDESHOW: EXCLUSIVE IMAGES OF ZACHARY QUINTO

One unexpected and happy consequence of playing Spock has been Quinto's relationship with Leonard Nimoy, who had a cameo in the 2009 film. "I have such deep admiration and love for him," Quinto says. "He's an incredible man, and I'm so grateful that not only did I have this amazing creative experience, but that I developed this relationship with Leonard and his wife, Susan -- we go to dinner, we hang out, we go to the theater, we spend time together."

There's something endearing in the specter of Spock the Elder taking Spock the Younger under his wing, and I'm reminded of a line in Star Trek, when Nimoy offers his young doppelganger the sage advice to "put away logic, do what feels right." It sounds like the kind of dictum that Quinto has taken to heart, both as an activist stumping for Obama's re-election and as an actor who is making increasingly interesting and eclectic choices.

As a young trader in last year's Margin Call, the absorbing, claustrophobic ensemble thriller about the banking crisis, starring Kevin Spacey and Jeremy Irons that Quinto produced and helped cast, he showed a flair for the kind of quiet understatement and internal conflict that distinguishes a subtle performance from an overwrought one.

And then there is Angels in America.

Quinto was standing in a coffee shop with Jesse Tyler Ferguson when he heard that Tony Kushner and the director Michael Greif were putting together an Off-Broadway revival of Kushner's monumental two-part play exploring America's response to the AIDS epidemic. He auditioned for, and secured, the role of Louis Ironson, the restless, conflicted heart of the play, and moved to New York City shortly after Heroes was cancelled. The experience was transformative, he says. He would spend hours walking around his neighborhood "just trying to fathom what that decimation [of AIDS] looked like, and what our history is as a community of gay people." He read Paul Monette's Borrowed Time and found it so terrifying, so bleak, that he had to put it down. "It really, really made me grow up inside myself," he says. "Any young person who is questioning their capacity for relevance, or their own self-worth, need only to learn about those people who had no choice -- they had to get out in front of, and express, the horrors they were faced with."

We have moved to a local restaurant, where Quinto orders himself a plate of lentils ("It's a hearty dish -- they're really good!") and conspicuously avoids the bread. We talk about his growing political role, which was energized by his interview with New York last year, in which he described the hopelessness he felt on reading about the suicide of gay teenager, Jamey Rodemeyer, a victim of bullying.

"One of the defining conversations that I had with myself was that absolutely no good can come from me staying quiet about [my sexuality]," he says. "Literally, no good can come from it. But if I take the step to make the acknowledgment and be honest, so much good could potentially come from it."

In the last six months he has expended a lot of energy campaigning for Obama, and his Twitter feed (more than half a million followers) reads like a daily call-to-action. He considers the election in November the most important in his lifetime. "It boggles my mind that there are so many extreme, Christian organizations that are adopting a stance against homosexuality with such vitriol and hatred and targeted aggression that goes against the tenets of the Christian faith," he says. "The hatred that people are leading with in this discussion is really, for me, the biggest symptom of how sick we are. It's the thing that makes me look at our culture and think, We are so far afield of any sort of connectivity or truth in relationship to one another." He pauses. "I don't want this to be too soapboxy," he says.

Although Quinto says he's chosen not to let his father's death define him negatively, he thinks the loss he experienced found expression in his early relationships. "I found myself in a pattern of being attracted to people who were somehow unavailable, and what I realized was that I was protecting myself because I equated the idea of connection and love with trauma and death," he says. "I had to do a lot of work on the couch to really get to a place where I was able to show up to a relationship with someone who was actually capable of being in one -- and that took a lot of trial and error. And I'm still working on all that stuff -- that will never stop. But I definitely want kids... I want to share."

Right now, the man he is sharing his life with is the actor Jonathan Groff, and although this is where he draws the line between what's private and what's public, he says, "I'm incredibly happy, I'm incredibly lucky," and we agree to leave it there.

SLIDESHOW: EXCLUSIVE IMAGES OF ZACHARY QUINTO

Quinto says that lately he's learned to slow down just a little. "I was never able to stop and just think, I've got a lot to be thankful for," he says. "In the last year, I've gotten to a point where I feel so fulfilled, even though it doesn't stop me from wanting to expand on that and do other things."

Often he thinks about the life his father led. "He was really, really badass and confident and sexy and intelligent and sensitive and curious," he says. "For years after he died, people would go out of their way to let me know how much he meant to them. And every time I heard it I was always so grateful to him for living that life. Now that I'm older, I know it's because that's what matters -- the things people can tell your child about you -- and I realize my father gave something really special to me even though he wasn't here to give it to me in person." He pauses. "People are going to be, like, 'I thought I was reading Out -- not Psychology Today.' " Maybe, I say, but this is what's interesting, surely.

"Good," he says. "It's what I find interesting, too -- bring it."