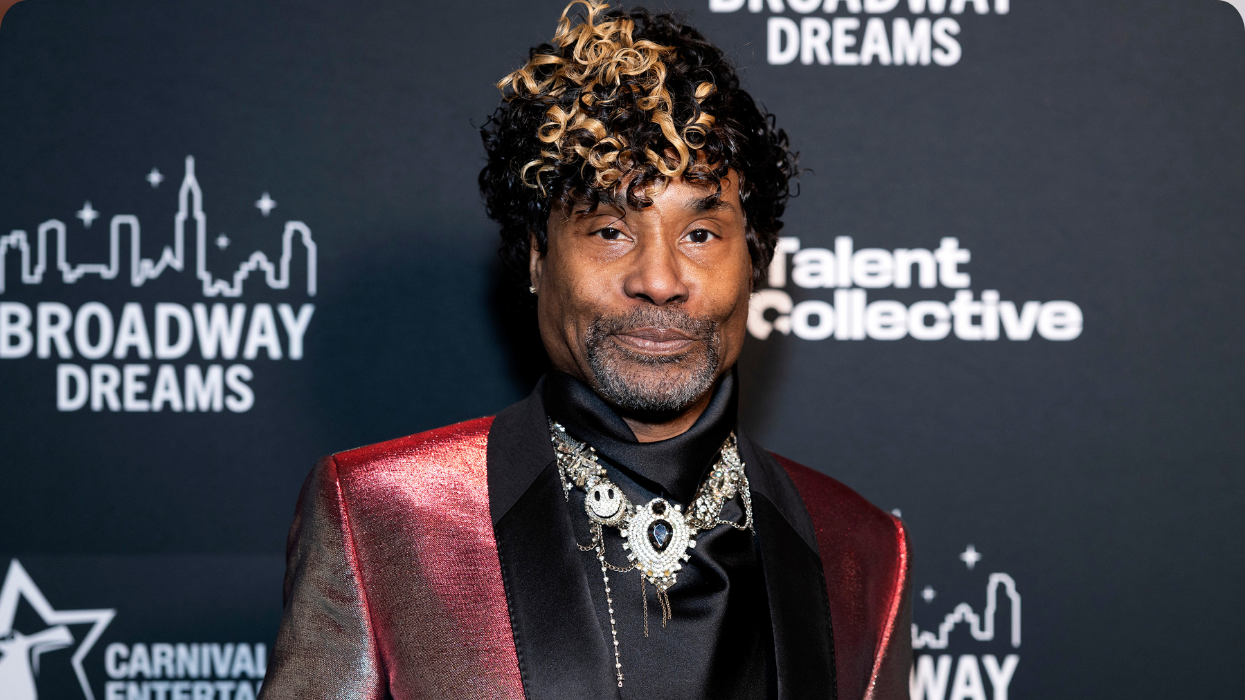

Photographer: Christopher Dibble

It's late July, and it's hot in Los Angeles. Not so hot that you'd want to ditch your clothes, but hot enough that Justin Simien needs to periodically dab his brow. The budding filmmaker is sitting across from me in the hip, yet un-air-conditioned, living room of an apartment in Koreatown. While we talk, a standing fan oscillates back and forth between us like a microphone, and though that image is apt for an interview with the man behind Dear White People, a movie that brilliantly celebrates the value of vocal exchange, what's most evocative is the heat.

A Sundance sensation, Dear White People is possibly the finest satire to tackle race relations since Spike Lee's 1989 masterpiece Do the Right Thing, which was famously set in Brooklyn on the hottest day of the summer, leaving the movie ripe for its ever-looming, boiling-point climax. Our meeting place's sweltry climate only amplifies my thoughts of Do the Right Thing, and the fact that Simien is also a black writer-director presents me with the kind of double-edged quandary in which Dear White People revels: Given his film's circumstances (and clear influences), I can't not ask Simien about Lee, yet in doing so, I'm inevitably putting him in a box.

"The real shame is that there haven't been more filmmakers of color that have had Spike's success and were also artistic, sophisticated, and stylish," Simien says. "I don't think I'm the next Spike Lee -- I have different things on my mind, and I don't necessarily have his sensibility. But I'm more than happy to walk through the door that he opened, because too few people have."

Simien's film -- his debut feature -- is tremendously topical, examining every nuance of the Miley-esque appropriation of black cultural hallmarks, while, on the flip side, exploring the tricky militancy of someone like Lee, whose rants against gentrification can be read as anti-progress. It's both impressive and disappointing, then, that Dear White People, which is set on a college campus that serves as a Petri dish of swirling, articulate ideas, began its journey a whopping eight years ago, when Simien, a Houston native, was still a student at Chapman University in Orange, Calif. "That's where the first draft [of the script] started to percolate," Simien says. It's also where Simien began to get a true taste of what it's like to be a black gay man in America.

Far from being simply about race, Dear White People covers what feels like every facet of modern identity, including the ills and necessities of labels in our culture, whether they're applied to ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation. Amid a vast ensemble, one character, Lionel (Tyler James Williams), is a queer, confused, and tellingly undeclared freshman. He claims he doesn't believe in labels, yet he yearns for a community, feeling adrift everywhere, especially around other black students. No character is fully reflective of Simien himself -- including Sam (Tessa Thompson), the "blacker than thou" campus DJ whose staunch views some filmgoers have presumed the director shares -- but Lionel comes from a very personal, very specific place.

"I really wanted to talk about the black gay experience," Simien says. "There is an image of the black man that is pervasive in the black community, and if you're gay and you know you can't ever live up to that standard, there's an anxiety about being comfortable around other black people. It's not always a result of actual prejudice, but it's an anxiety that the black gay guy has that I think is unique."

Similar anxieties can spill over into the world of dating, as when Lionel, finally bold enough to experiment with a male peer, finds that he's viewed as little more than an exotic conquest. "I was in a dating scenario where I went down a road with someone to discover that I'd been fetishized the whole time," Simien says. "Navigating the gay male community, even among other black guys, is a very nuanced experience. Men can be very specific about what they're looking for, and adding the layer of race to that creates some awkward, strange culture toggling. There was a moment in college when someone's wingman came over and tried to hook me up with him by saying, 'Yeah, he's really into black guys like you.' Why would that turn me on?"

Another moment in college, perhaps the most seminal of all, came about in a debate class, where two student groups, the Young Republicans and the Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Alliance ("I think that's what we were called," Simien says) argued the issue of gay marriage. This was roughly 10 years ago. "I was just so heartbroken to hear some of the things my peers were saying," Simien says, his shoulders slumping abruptly.

The director channeled these reactions into his student thesis film, dubbed Rings, which follows two women on what seems to be a path to marrying each other, only to reveal that they're sisters, and that one of them, a white woman, is marrying a black man. "The film strives to make the comparison that this is all the same bullshit we were doing before," Simien says. "No one would ever think to quote the Bible now to discourage a black and white person from getting married, but we're doing the same exact thing to a new minority group."

It was around that time that Simien, though insisting he's never been big on announcements, decided to be out and open for good. Knowing what he could have gained from seeing a black gay man like him in the public eye, he wanted to be sure that if all went well, and "people wanted to interview [him] about [his] movie one day," there'd be nothing to hide. Sure enough, at the first Sundance Q&A for Dear White People, the then-unknown filmmaker was asked where he "got the idea of having a black queer character." He responded, "Well, I am a black queer character."

More often than not, Simien is smiling widely, while slightly adjusting the fedora he treasures like a protective helmet. He says that for all the lasting relevance of his eight-year-old passion project about various racial injustices (or, in a film where no one is right or wrong, perhaps just misunderstandings), he sees a world of optimism. He even finds value in the onslaught of ignorant social media users, whose worst comments can at least remind us, for instance, that a "post-Obama America" and a "post-racial America" are far from synonymous. And one thing he won't do is drown his work in tragedy, a practice that, even with strong filmmakers telling stories from their own communities, has resulted in a certain gloomy ghettoization in the worlds of black and queer cinema.

As for the issue of labels, Simien acknowledges that it's a rabbit hole, one we can go down only so many times during our discussion, but one that someone could spend a lifetime -- or a career -- exploring. Like his characters in Dear White People, he's always been privy to the idea that "so much of success in America depends on the ability to play up to, or play against, your label" (for instance, Simien admittedly advanced himself by "disarming people" with token gay traits when he worked in publicity, but lamented the constant expectation of having "the black opinion in the room"). "The conflict between identity and self is age-old and profound," Simien says. "I honestly feel like that will probably be my life's work -- to talk about that."

Dear White People opens in cinemas Oct. 17. Watch this clip from the film below: