Popnography

CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

Scroll To Top

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

So how does one convey homosexuality as a central plot point without actually, you know, spelling it out? In The Children's Hour, it's alluded to as a shadowy, inconceivable terror, like Lord Voldemort or Karl Rove -- a schoolgirl's eyes nearly pop out of their sockets when she is shown reading a smutty novel; an elderly woman screams in the back of her car as her granddaughter whispers what she saw Hepburn and MacLaine doing one night through the keyhole of their bedroom door. Other attempts are pure wordplay, with vague terms like

"unnatural" and "funny" that suggest the unsightly. If anything, The Children's Hour, whose moral conclusions regard the power of lies rather than the treatment of gays, clearly reflects the pursed-lipped society from which it came.

Victim, on the other hand, tackles its subject matter progressively when compared to its American contemporary. Before viewing it, I assumed the first cinematic proclamation of "homosexual" would be

shrouded in the type of Hollywood climax that accompanies the unveiling of massive secrets. But it's spoken within the first 25 minutes, by a police detective, in reference to a young man who's just committed suicide in his jail cell. The deceased, "Boy" Barrett, had been photographed in an emotional exchange with a powerful lawyer on track to become a national judge. Barrett's thefts, for which he was arrested, supported his payments to a blackmailer who was anonymously mailing copies of the photo, accompanied by menacing notes and

phone calls.

According to the film, in Britain in the 1950's and '60s, ninety percent of all blackmail cases involved gay men. Given the clandestine nature of blackmail, the real statistic is unknown, but the estimate is entirely realistic. It wasn't until the amendment to the Sexual Offenses Act in 1967 that homosexuality was

officially decriminalized by the British government. And up until that point, men and women could be jailed upon being discovered. One particularly disturbing case involved the famous mathematician and cryptanalyst, Alan Turing, who in 1952, upon disclosing the details of a sexual relationship with a 19-year-old boy to the police, was given the options of going to jail or undergoing hormone therapy. He chose the therapy -- "chemical castration" through estrogen injections -- and committed suicide two years later.

Victim, for the most part, vividly reconstructs this world in which blackmailers are actually aided by a legal

Catch-22: if the men report their extortionists to the police, they face the risk of being arrested or ridiculed in a public trial. On top of this, blackmailers are easily able to infiltrate the gay scene in London by juicing their victims for salacious details in lieu of money. Duplicity and cowardice are exploited

to their most lucrative potentials with no real check, except, perhaps, Barrett's alleged lover, Melville Farr.

As a counterpoint to the reticent men looking over their backs in Soho, Farr (played by Sir Dirk Bogarde, then an English heartthrob) preempts his impending blackmailer by hitting the streets. The established lawyer has much more at stake than his deceased lover -- a wife, a reputation, a giant office -- but he is motivated, perhaps by a desire to atone for past indulgences, to expose the true criminal at hand. This characterization is sometimes hard to swallow, as Farr seems somewhat unfazed by the consequences of his actions. He also seems diametrically opposed to the gay archetypes established onscreen -- gay men as victims, as ashamed perverts, as cowards, etc. -- for which the film has taken some criticism.

In this vein, Farr and, generally, the film, treat the actual concept of gay sex and relationships with the same shadowy aversion as The Children's Hour. The raciest divulgence sounds like this: I repeatedly gave him a ride home in my car. (Whatever that means!) And we are never actually gain access to any of the incriminating photos utilized for blackmail. Farr, in particular, takes pride in distancing himself emotionally from his past flings and mentions none of the details that would most likely have gotten the film banned in the U.K. Even Farr's wife, who is quite aware of the situation, is able to overlook her husband's physical appetites for his claims of eternal love to her. Of course, these examples are the vestiges of a society convinced that homosexuality was a trait that could be cured, whether by jail time (fat chance) or hormone therapy or whatever else.

But in Victim, what's considered particularly risque is the directness of the script. The men being blackmailed are all "homosexual" or "queer" -- none of this wishy-washy "different"/"unnatural" business. There's the strong indictment against the criminalization of homosexuality, which was radical and alienating for audiences at the time. And the film proved that cinema can be a catalyst for public awareness where other means fail. After its run, Victim was nominated for two BAFTA Awards in 1962, one for Bogarde's role, which many actors would've turned down.

Obviously, Hollywood is no gold-star student when it comes to homosexuality. Many actors are still closeted, and gay roles are still mainly considered Oscar bait for straights. We usually have to wait a year in between the releases of our larger films, many of which use homosexuality as a gag or a lazy fetish. I frequently wonder if things are progressing at a much slower rate for the film industry, even now, when gay discrimination is not nearly as prohibiting as it once was.

Maybe that's the point. I think of Bogarde, who may have been too familiar with his own role in Victim. The acclaimed actor was closeted and somewhat of a life-long bachelor. His appearance in such a film was extremely brave at a time when his actual freedom was at stake. Perhaps I'm romanticizing something I was never a part of. But I wonder if such monumental performances may be lost in an era where big-budgeted gay films are considered passe and annually requisite.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

41 male celebs who did full frontal scenes

September 16 2024 2:02 PM

39 LGBTQ+ celebs you can follow on OnlyFans

November 19 2024 9:39 AM

33 actors who showed bare ass in movies & TV shows

September 17 2024 5:43 PM

26 LGBTQ+ reality dating shows & where to watch them

December 10 2024 12:38 PM

21 times male celebrities had to come out as straight

November 19 2024 3:33 PM

17 queens who quit or retired from drag after 'RuPaul's Drag Race'

November 30 2024 12:26 AM

52 steamy celebrity Calvin Klein ads we'll always be thirsty for

August 27 2024 1:08 PM

15 things only bottoms understand

October 08 2024 5:18 PM

15 gay celebrity couples who make us believe in love

October 03 2024 5:43 PM

A gay adult film star's complete guide to bottoming

September 16 2024 8:50 AM

Latest Stories

Netflix to stream Women's World Cup—these queer soccer players paved the way

December 21 2024 12:00 PM

Celebrating extraordinary leaders of the Out100 Special

December 21 2024 9:00 AM

Ranking the top 10 albums released by LGBTQ+ artists in 2024

December 20 2024 7:20 PM

Frotting vs. Frottage: Here are the key differences you should know

December 20 2024 6:50 PM

What's your battle cry? The 'Wicked' sing-along album is finally here

December 20 2024 6:15 PM

What is T-Boy Wrestling? Learn more about this sport for trans men

December 20 2024 3:48 PM

Where and how to watch the 2024 Out100 Special

December 20 2024 3:37 PM

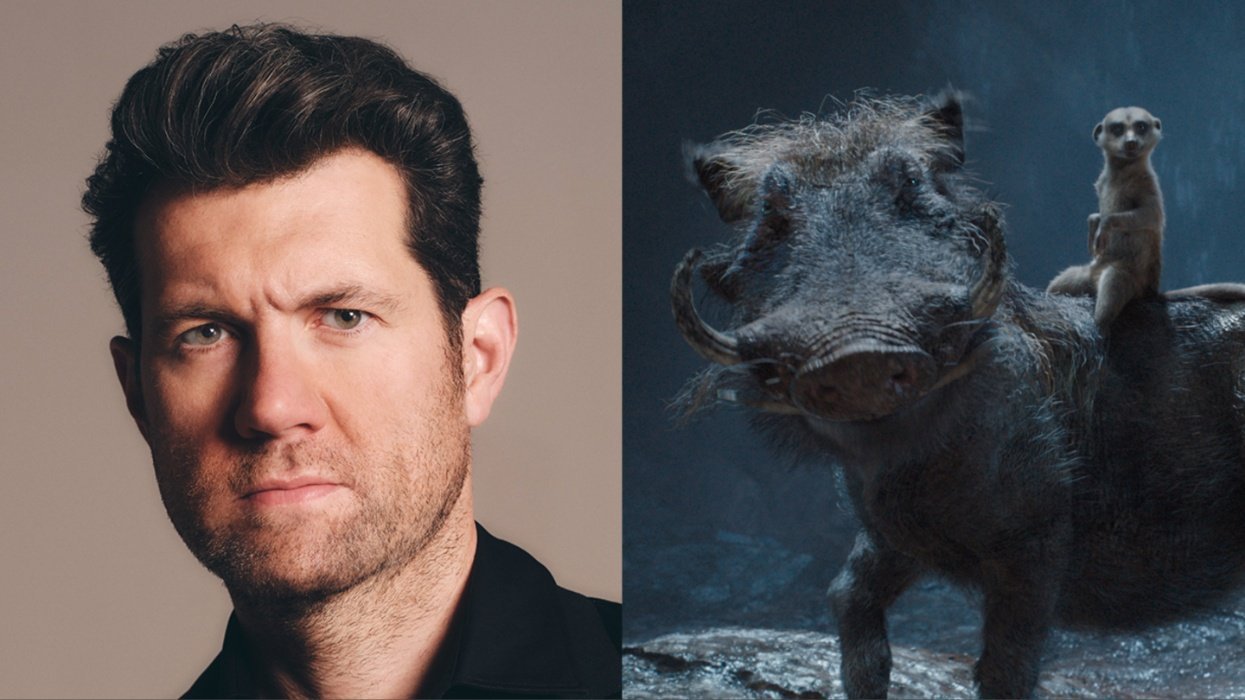

Out and About with Billy Eichner

December 20 2024 3:28 PM

35 pics of David Barton & Susanne Bartsch Toy Drive 2024

December 20 2024 1:16 PM

Friday, December 20

December 20 2024 12:10 PM

Brian Jordan Alvarez accused by former costar of sexual assault

December 20 2024 9:42 AM

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right